News

Why South Africa is Suddenly in Love with International Justice

South Africa’s sudden pivot towards using the global judicial architecture is as surprising as it’s contradictory and disingenuous.

Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Research Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Just last year, President Cyril Ramaphosa was preparing to host Russia’s President Vladimir Putin at the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) summit in Johannesburg following frequent one-on-one meetings between the two.

When it became clear that a court would rule that South Africa would have to arrest Putin in terms of a warrant issued by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes related to his invasion of Ukraine, the government relented, and Putin attended the summit virtually.

In April, Ramaphosa had gone so far as to say that the African National Congress (ANC) had agreed that South Africa would pull out of the ICC following its issuing of the warrant.

In an extraordinary public statement made at a media conference with the visiting President of Finland, Sauli Niinisto, he said, “Yes, the governing party … has taken that decision that it’s prudent that South Africa should pull out of the ICC.”

The ICC had lost its legitimacy because of its treatment of “certain countries”.

“We would like this matter of unfair treatment to be properly discussed, but in the meantime, the governing party has decided once again that there should be a pull-out.”

When it became apparent that it would be impossible for this “pull-out” to be exercised before Putin visited the country, Ramaphosa halted the withdrawal.

Prior to that, South Africa had refused to arrest then Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, who was charged with a litany of war crimes. Among these were, to quote the ICC, “five counts of crimes against humanity: murder, extermination, forcible transfer, torture, and rape; two counts of war crimes: intentionally directing attacks against a civilian population as such or against individual civilians not taking part in hostilities, and pillaging; three counts of genocide: by killing, by causing serious bodily or mental harm, and by deliberately inflicting on each target group conditions of life calculated to bring about the group’s physical destruction, allegedly committed at least between 2003 and 2008 in Darfur, Sudan”.

South Africa was unmoved by these alleged gross violations which occurred on African soil. Instead, the government ignored a Supreme Court of Appeal order that South Africa had a duty to arrest Al-Bashir in terms of domestic and international law, and that its failure to do so was “unlawful”.

Fast forward to January 2024, and South Africa has done another 180-degree turn.

On 7 October 2023, Hamas launched a bloody terror assault on Israeli military and civilian targets, killing 1 200 people including youngsters attending a music festival. Footage of the assault was distributed on social media by the assailants, and included the bloody, naked corpses of young women being paraded about amid cheering and celebration.

The department of international relations and cooperation (Dirco) issued a press statement which was notable for its failure to condemn the assault. Instead, it spoke of “the recent devastating escalation in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict”, without referring to the widespread incidents of terror.

Instead of condemnation, it sought to justify the assaults, saying, “The new conflagration has arisen from the continued illegal occupation of Palestine land, continued settlement expansion, desecration of the Al Aqsa Mosque and Christian holy sites, and ongoing oppression of the Palestinian people.”

When Israel retaliated, South Africa withdrew its diplomatic personnel from Israel in protest, and put the wheels in motion to close down Israel’s embassy in South Africa. They were beaten to the punch when Israel recalled its ambassador before they could fulfil this objective.

As if to underscore that South Africa would, just as it had done with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, swallow the narrative of one side – in this case, Hamas – hook, line, and sinker, International Relations Minister Dr Naledi Pandor placed a call with Hamas and appeared in Tehran at a meeting with the Iranian foreign minister.

Any hope of South Africa presenting itself as a powerful mediator vanished as it took sides, and, apparently oblivious to the irony, it went so far as to end the year with a formal request to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to investigate Israeli (but not Hamas) actions, which it described as “genocide”.

Attempting to explain the condemnation of Israel and the condonation of Russia, Dirco Director General Zane Dangor produced these verbal gymnastics:

“Recently, I was asked why South Africa is so clear in its support for the people of Palestine and not for the people of Ukraine. While we could have been clearer in many aspects of our response to the war in Ukraine, and this could be the subject of another article, there are a few areas that we were very clear on.

“While we may have stated that we understood Russia’s security concerns with regards to Nato’s [the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s] expansion, we were very clear that the use of force by Russia on Ukraine was unlawful. We were also very clear that the acquisition of territory through force was unlawful.”

The truth is somewhat different. South Africa abstained from resolutions condemning the unlawful occupation of Ukraine and even from a resolution on humanitarian aid to Russia, and then conducted military exercises with Russia while conducting frequent high-level defence and foreign-affairs engagements.

Among those on South Africa’s legal team to prosecute Israel for genocide is Professor John Dugard. Overlooked for the Constitutional Court and then overlooked for the position of head of South Africa’s Human Rights Commission by the ANC after it came to power, it’s not without irony that Dugard is now on the payroll to polish up the ANC’s human rights credentials.

In an ironic twist, given Dugard’s anti-apartheid history, the Gaza conflict illustrates the obstacles faced in defence in a democracy. Whereas authoritarians are hardly bound by normative constraints – viz Putin’s attack on Ukraine – democracies are vulnerable to the court of international public opinion because they are – and should be – held to higher standards. The invasion by Hamas into Israel on 7 October 2023 and the subsequent invasion of Gaza by Israel in response and the claims, thereafter, of Israeli genocide are an example of this contradiction and the manner in which terrorist organisations hide behind international standards that they have no intention themselves of upholding. On the one hand, as international lawyer Daniel Taub has argued, authoritarian regimes and organisations create impossible dilemmas on the ground for any democracy trying to defend itself; and on the other, the democracies face a manufactured multilateral legal minefield in the criminalisation of their armed defence.

South Africa’s pivot to a radical foreign policy and war through lawfare raises two additional questions: why this turn, and what might be the implications?

On the former, there are domestic and international dimensions. As electioneering hots up ahead of the 2024 national and provincial election, the ANC’s cupboard is bare. It’s losing support hand-over-fist following a litany of domestic failures in energy generation, transport logistics, job creation, and the rapid decline in the delivery of basic services.

Its sudden commitment to the institutions of international law shouldn’t be mistaken for principled interventions, it’s motivated by the desire to distract from these domestic failures by focusing attention elsewhere; to burnish its radical credentials through its foreign policy; and no doubt to seek funding for empty ANC election coffers.

No matter the schizophrenia in supporting Putin’s neo-colonialism in Ukraine, the recent twists and turns in its foreign policy illustrate South Africa’s intent in changing the terms of the current rules-based international order, including the nature of the Bretton Woods regimes and the structure of the United Nations. In BRICS lies the seed of an alliance to change these rules, through Russia and China of course, but also other allies including Venezuela or Iran.

It’s unlikely that the blind eye turned by the West towards South Africa in its radicalisation journey from BRICS through the Lady R to the ICJ has helped. Perhaps this is because the West has substantial interests in South Africa – financial and familial – that it wishes to protect and preserve, or it may be because it prefers the fairytale version of the 1994 walk to democracy and doesn’t wish South Africa to present a new problem on its already cluttered foreign policy radar. Either way, ignorance isn’t bliss, and nor will it revive the jaded romance. More likely is increased constraints on the high-tech Western arms transfers to South Africa necessary to keep its fighters flying and frigates sailing, and a higher risk premium by increasingly sceptical debtors and investors.

And as the ANC’s domestic record cuts into its electoral support, anticipate more focus on international relations. At the same time, democracy will be under its most severe test as the ANC loses its grip on power, a struggle in which, if its authoritarian friendships are any gauge, a Stalingrad approach may well become the norm.

But also expect that this pivot away from the West is no longer entirely cost free, a price that will be paid by all South Africans.

This article originally appeared in the South African Jewish Report

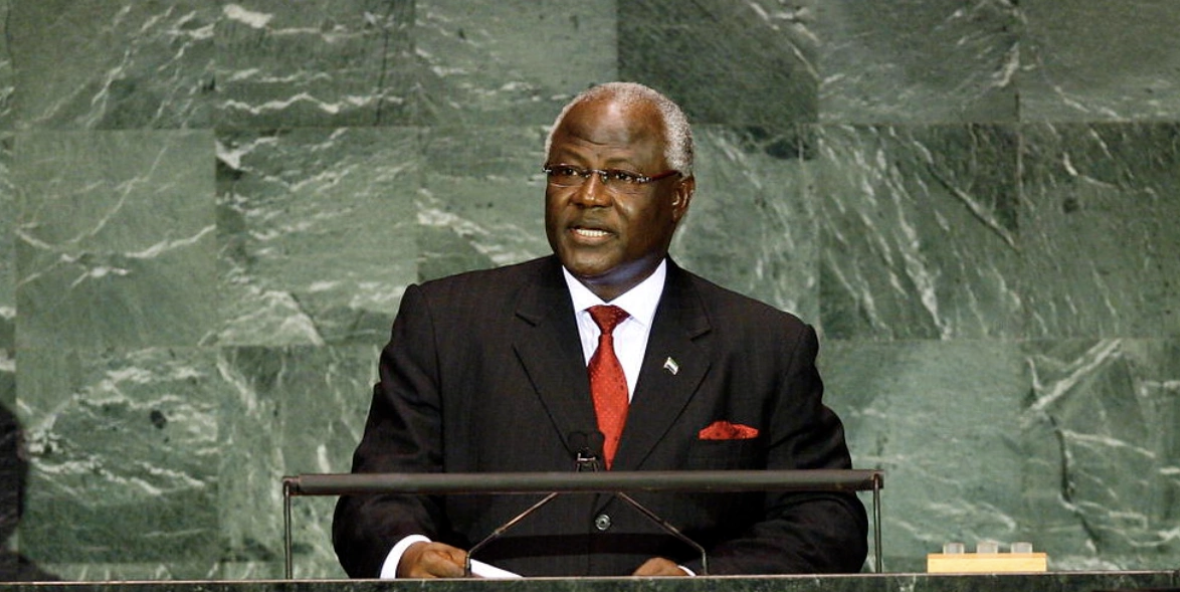

Photo: GovernmentZA Flickr