News

‘Unfree, Unfair’: The Post-Election Danger of Harare’s Unchecked Course

All eyes will be on South Africa, which, although somewhat jaded by corruption scandals and a declining state, still claims to be the leading democracy in the region. Now that SADC observer mission has condemned the Zim election, it has nowhere to hide.

Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Research Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Predictably, Zimbabwe’s ruling Zanu-PF has declared victory in an election so bad that even the usually obsequious SADC essentially declared it unfree and unfair.

The SADC mission noted that “aspects of the Harmonised Elections fell short of the requirements of the Constitution of Zimbabwe, the Electoral Act, and the SADC Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections (2021)”.

So sad, say commentators about a country where the population is 25% poorer than they were in 1974. The world is, by comparison, twice as wealthy.

But it’s not sad – it’s bad.

It’s bad for Zimbabweans. In the words of veteran opposition leader and former Zimbabwean finance minister, Tendai Biti:

“Millions of Zimbabweans hoped for change. They hoped to be delivered from the scourge of unemployment, poverty, decayed infrastructure, collapsed public services, captured institutions, violence and an exhausted liberation movement that continues to hold them hostage.”

It’s bad for the region. A fragile region, already looking after more than two million Zimbabweans, now has to face the implosion of a fresh wave of Zimbabwean immigrants.

And it is bad for South Africa.

Also, perhaps more importantly, it raises a question: What should insiders and outsiders now do differently?

Limp Commonwealth response

After nearly two decades of targeted sanctions, the appetite in the West to continue to exclude Zimbabwe has waned. As one indicator, the Commonwealth’s response to the election was predictably limp:

“In conclusion,” it reads, “our overall assessment of the voting process is that it was well conducted and peaceful.”

Perhaps SADC and the Commonwealth were in different countries?

Apparently, for the Commonwealth, “well-conducted” includes many polling stations opening at dusk and no ballot papers delivered for most of the election day, forcing a second day of equally poorly managed voting.

They were also unmoved by a security intervention to prevent Zimbabwe’s NGOs from monitoring the election and the throttling of the internet.

Sadly, they have fallen for the new approach to election rigging which has taken hold: Don’t kill anyone on election day while the observers are earnestly taking notes, and then control the counting process which inevitably takes place behind closed doors.

And yet it was the Commonwealth that established democratic norms under the 1991 Harare Declaration.

“We believe in the liberty of the individual under the law, in equal rights for all citizens regardless of gender, race, colour, creed or political belief, and in the individual’s inalienable right to participate using free and democratic political processes in framing the society in which he or she lives,” reads that Declaration.

No doubt others, including Washington, will be waiting to see how Africa responds. The administration is aware of how US sanctions are perceived.

More than being worried about democracy, there will be concerns about what measures will be counter-productive to Western as well as other interests, especially in the light of growing geopolitical competition in the subcontinent.

There are also concerns about the possibility of violence in the near term.

The Biden administration apparently believes it has a special relationship with the liberation movements of the region, even though their claim to represent their people has worn thin as election after election is rigged.

Outsiders will have to be led by what the opposition wants.

While outsiders will be trying to prevent violence, that is not actually their role – like humanitarian assistance, this form of external intervention has simply perpetuated the Zanu-PF regime. They get away with outlandish election stunts and rigging because the outside world allows them to do so in the name of peace.

That should not be the job of outsiders more than an acceptance of stability over democracy is a judgment call of international election observers.

South Africa under scrutiny

All eyes will also be on South Africa, which, although somewhat jaded by corruption scandals and a declining state, still claims to be the leading democracy in the region. It usually avoids offending its neighbouring comrades by claiming it is led by the views of “multilateral institutions”. But, now that SADC observer mission has condemned the election, it has nowhere to hide.

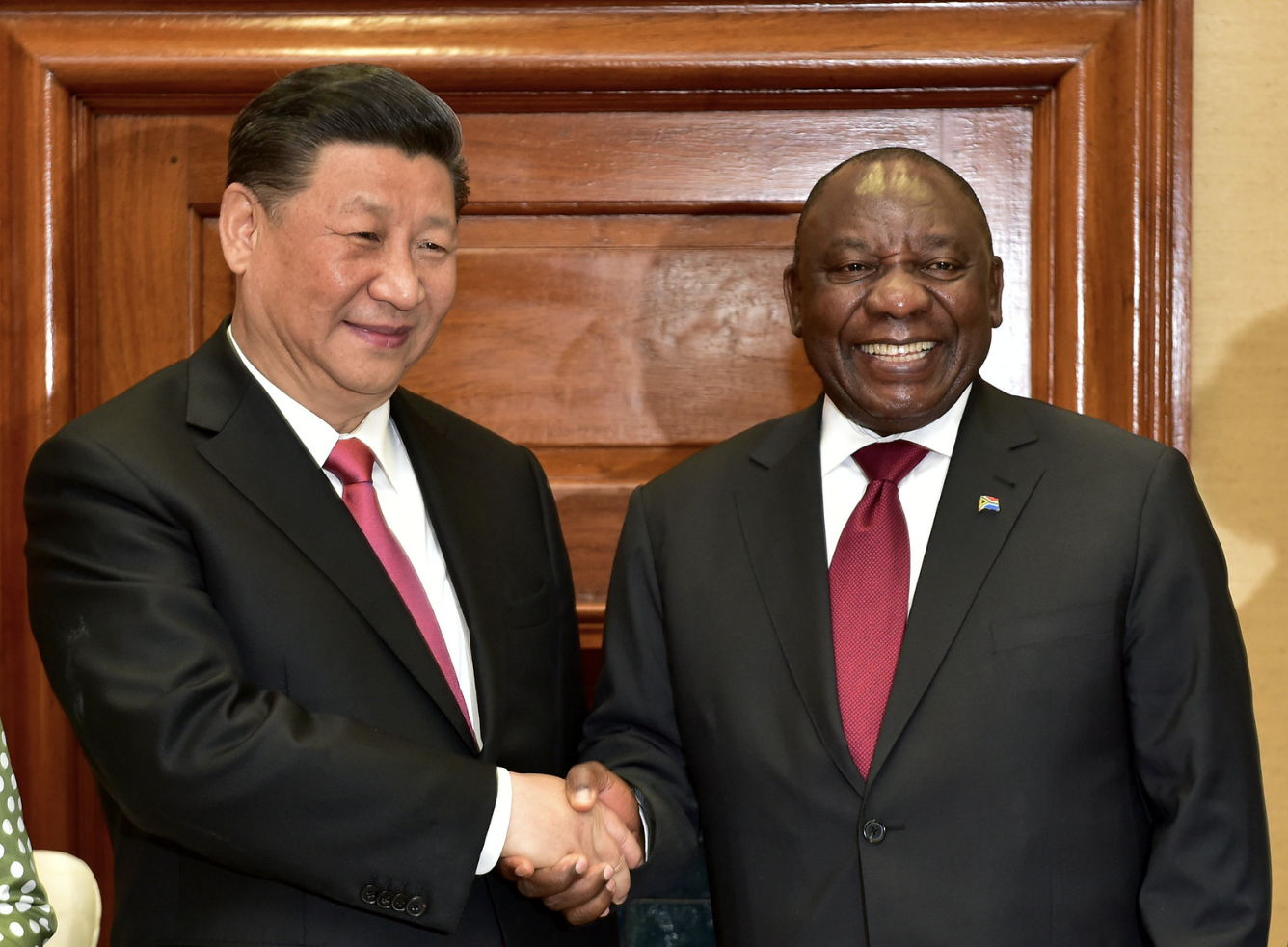

Will SA continue its opportunistic approach to foreign policy, which has seen it hide the light of democracy under the bushel of subservience to China and Russia?

According to Biti: “Whatever South Africa does or does not do, SADC surely must act on its preliminary report. Having concluded that the election was not free or fair, SADC must take corrective measures and provide the agency and leadership required.”

SADC could follow its own precedent.

“When Mugabe brazenly and violently stole the 2008 run-off election, it appointed then-president Thabo Mbeki to facilitate dialogue on an internal solution in Zimbabwe. However, any intervention or solution to the Zimbabwean crisis must be founded on democracy and respect for the people’s will.

“A preference for stability over democracy would be a disaster,” said Biti.

He went on to say that “any intervention must be an inclusive process that involves the broad mass of Zimbabweans. In addition, any such intervention must recognise the huge economic, political and legal reforms that have to be carried out.

“Lastly, in light of the military coup of November 2017, any solution must address security sector reform. Given the enormity of what needs to be done in Zimbabwe, a provisional government or a national transitional authority is a possibility worth considering.”

Zimbabwe’s opposition

Then there is the question of how Zimbabwe’s long-suffering opposition should react.

In the short term, it will have to prove that it won by collating the V11 reports [polling station result forms] to make its tally. Since these forms are at the polling station level, they are the least likely to be tainted and will provide an accurate guide to what really happened in the election, rather than Zanu-PF’s version of results.

In the longer term, however, the opposition Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC) will have to review its election strategy. While the CCC picked up support and has prevented a two-thirds Zanu-PF parliamentary majority, this is not enough to take the country out of its dire economic mire. On the contrary, it may even sideline parliament from its role in scrutinising the exercise of executive power.

Where the CCC failed was in believing that the righteousness of its mission was enough to secure its results. It should rather have learnt lessons from Hakainde Hichilema’s election victory in neighbouring Zambia in 2021.

Hichilema learnt from past mistakes. He built a system with comprehensive monitoring and observation across polling stations and during the counting process. His UPND party reduced the room for manoeuvre for shenanigans. More than that, he built a national base, assiduously building cross-ethnic support.

He also won big, at least big enough that even the inevitable fiddling by government would not matter, or would be so egregious that even the one-eyed election monitors would notice. To ensure he had a measure of insurance, he also constructed a system of international allegiances that would help to keep observers vigilant.

Instead, in Zimbabwe, the exclusion of certain CCC stalwarts from the party ticket smacked of insecurity on the part of its leadership. The CCC was poor, too, in servicing its international relations; its leader preferring not to travel to events that would have proven important for support and funding.

As it regroups, the CCC will have to build a broad base of internal and international support. It should stop pretending that it does not like sanctions and call for them to be widened and deepened against Zimbabwe’s illegitimate regime.

It needs to ask the international community – including the spineless Commonwealth and African Union – whether their elite interests should trump human rights.

As for the West, the CCC needs to ask those who share its values to give democracy a chance by starving authoritarianism of financial oxygen.

Democracy has suffered yet another setback in Zimbabwe this past week. If the rot is not stopped there, this time around, it will have costs in South Africa and farther afield.

What hope is there for democrats if other democrats do not come to their aid while authoritarians bandy about in support of each other?

South Africa has a major election looming in 2024 where the ruling ANC is expected to drop below 50% for the first time. The country’s blooming romance with the likes of China, Russia and Iran does not exactly inspire confidence that democracy will be defended at all costs.

Silence on this appalling election to the north will cement scepticism about the ANC’s intentions.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa has said in response to his government’s announcement of his “victory” that “elections have come and gone”. He does not care about the niceties of public and human rights.

He cares about money and power and will stop at nothing if not stopped.

This article originally appeared on the Daily Maverick

Photo: World Economic Forum