News

Ukraine Crisis — The End of the Beginning, or the End of the End?

'Now this is not the end,' observed Churchill following the Allied victory at El Alamein. 'It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.' Which category does Russia's war in Ukraine fit into?

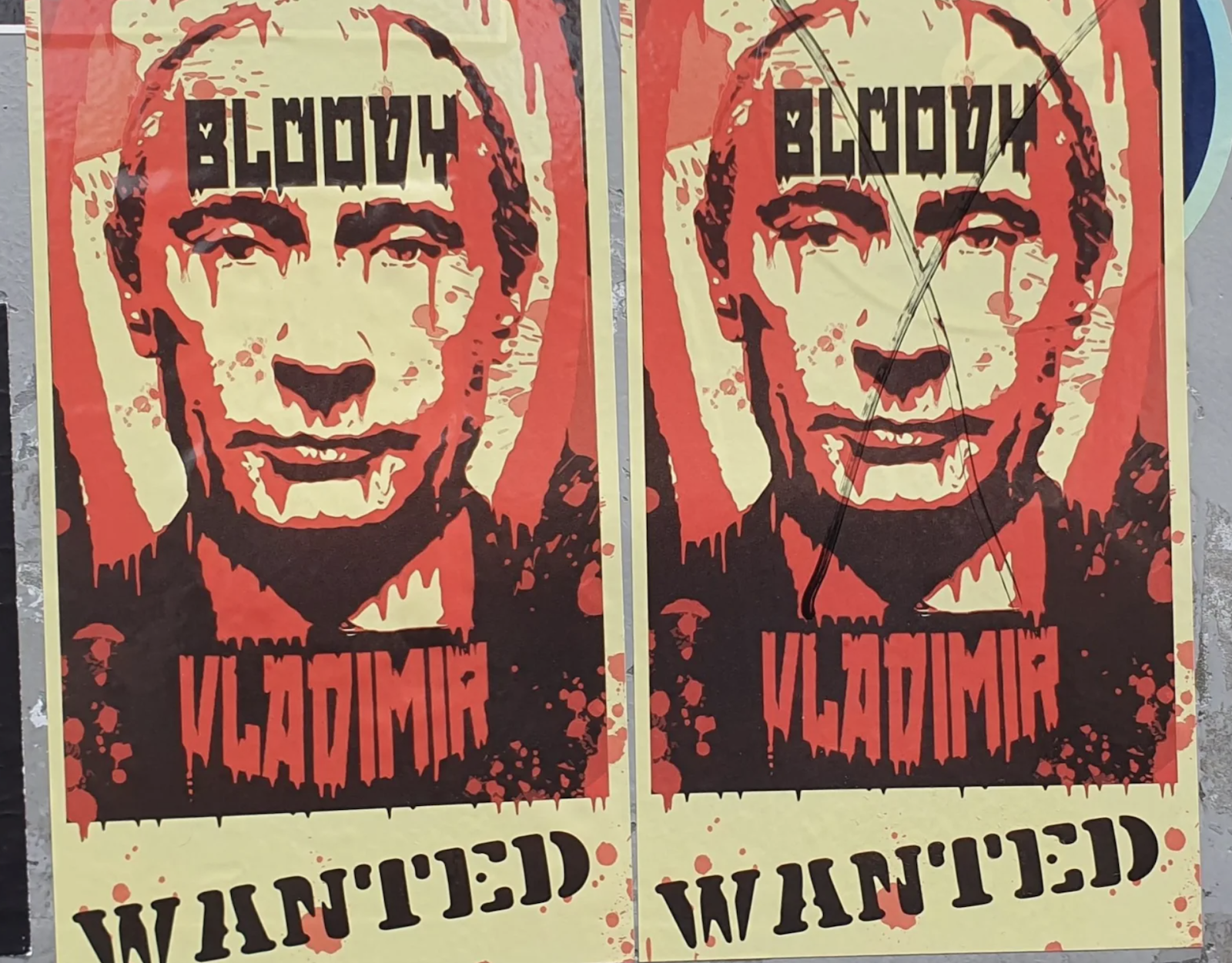

Some see Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin's move on Ukraine as signalling a return of history, the end of the beginning of a new Cold War, a redrawing of clear spheres of interest between East and West, between two political world views and systems. One is committed to liberal democracy and the expansion, however imperfectly and sporadically, of open systems of government and economic interaction, the other to authoritarianism and an economy built on oligopolistic access and preferences.

But what if this is not the case? What if Putin's move is essentially the last roll of the dice for this “old” Cold War, that a combination of globalised communications and technology is today an unstoppable force for the universalisation of values and the opening of opportunities beyond national boundaries?

We have been here before.

Francis Fukuyama's 1992 The End of History and the Last Man predicts the global triumph of political and economic liberalism. The book expanded on his essay “The End of History?” published in 1989 just months before the fall of the Berlin Wall that November, in which he wrote: “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

Critics contended that Fukuyama was wrong in that subsequent events prove that history has turned out differently, and that he was incorrect too in celebrating American-style democracy as the ultimate form of government. But Fukuyama, who served in the US State Department's policy planning section before reverting to academia, has written that it was more the model of the European Union and its version of transnational power than America's “continuing belief in God, national sovereignty, and their military” that he had in mind for his thesis.

Others criticised The End of History because it failed to note the rise of ethnic and religious loyalties which would replace ideological divisions as a source of disorder. And the failure to mention the brutal Chinese crackdown on Tiananmen Square which challenged his core narrative was a notable omission. Harvard academic Samuel Huntington's 1993 essay (and 1996 book of the same title), “The Clash of Civilizations”, argued, for instance, that the conflict between ideologies was to be replaced by a more prosaic and enduring conflict between civilisations, especially Islam. The events of 9/11 gave prominence to this critique, that history had, in the words of one critic, “returned from vacation”.

But Fukuyama is not alone.

Lech Walesa is one of the last of the pantheon of leaders who oversaw the disintegration of the Soviet Union. More than that, the Polish electrician-turned-unionist-turned-president perhaps more than any other Eastern bloc leader catalysed the collapse of a system which, while many saw as rotten, few offered a route out of its crushing combination of totalitarian politics and command economics. “We were fighting for something different. I was fighting for a new era, for one of information and globalisation” he says from his Foundation's headquarters at the European Solidarity Centre in Gdansk. “In Europe we had to construct bigger structures than national states.”

He compares the European process of enlargement to Putin's ambitions in Ukraine. “Russia is trying to enlarge its empire to include Ukraine. We did it through inclusion; they are trying to do it through conquest.” Walesa, 78, notes that “Russia, a big country with a catastrophic political system like China, has to be changed unless it changes us to be like them.”

“We are now fighting with the causes of Russia's invasion, which is a terrible political system. If Putin was leader for just two terms as he should be, the world would never have these problems.”

Walesa says that the problems are also of the West's making in that “I wanted to go into NATO with Ukraine and Belarus. But Madeleine Albright convinced me not to do so. But,” he adds, “we should have done so and will do so. To dissolve the Warsaw Pact, we had to act decisively and with courage, in a tough way. This is not how the world is talking to Putin.”

How should the outside world — at least those who favour international law, democracy and human rights — react right now?

The answer lies in part in what the West does and what it doesn't do.

For one, it will depend on whether sanctions can be maintained, not only for the challenges of income and technology access that this poses to the Russian war machine, but for the domestic effect. It is unlikely that the Russian population will be too chuffed when they can't get their German or Korean washing machine or BMW repaired and have to resort to washing in a bucket and a trundle in the family Lada. There will come a point when the aspirations of the people can't be met. The history of the USSR is a salient lesson in this respect.

Providing Ukraine with political support is one thing, but it will also require enough military means and economic resources so that the rules of supply and demand take their course, dispatching Putin and his ilk finally to the past. Walesa sees it this way. “What we are having right now is the progression of civilisation, where Russia and China are dragging behind. It's only a question of how many bruises are made and blood spilled until the world realises that we are in a new era, of intellect, digitisation and globalisation.”

If this is correct, then we are seeing the very end of the Cold War.

This article originally appeared on Daily Maverick.