News

This is the way the world ends: Not with a bang, but a whimper

Four Hiroshima-bombs worth of heat is released into the Earth's atmosphere every second as a result of human industrial activities, most of which is absorbed by the oceans.

Former Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Former Researcher, The Brenthurst Foundation

There is much good in Asia’s development path, not least the commitment to popular welfare displayed by its leadership, and the laser-like focus on jobs and growth. Equally, there are things to avoid. In particular, while fossil fuels form the foundation of many Asian countries’ electricity supply, notably China’s, there are good reasons why Africa should not follow the same path.

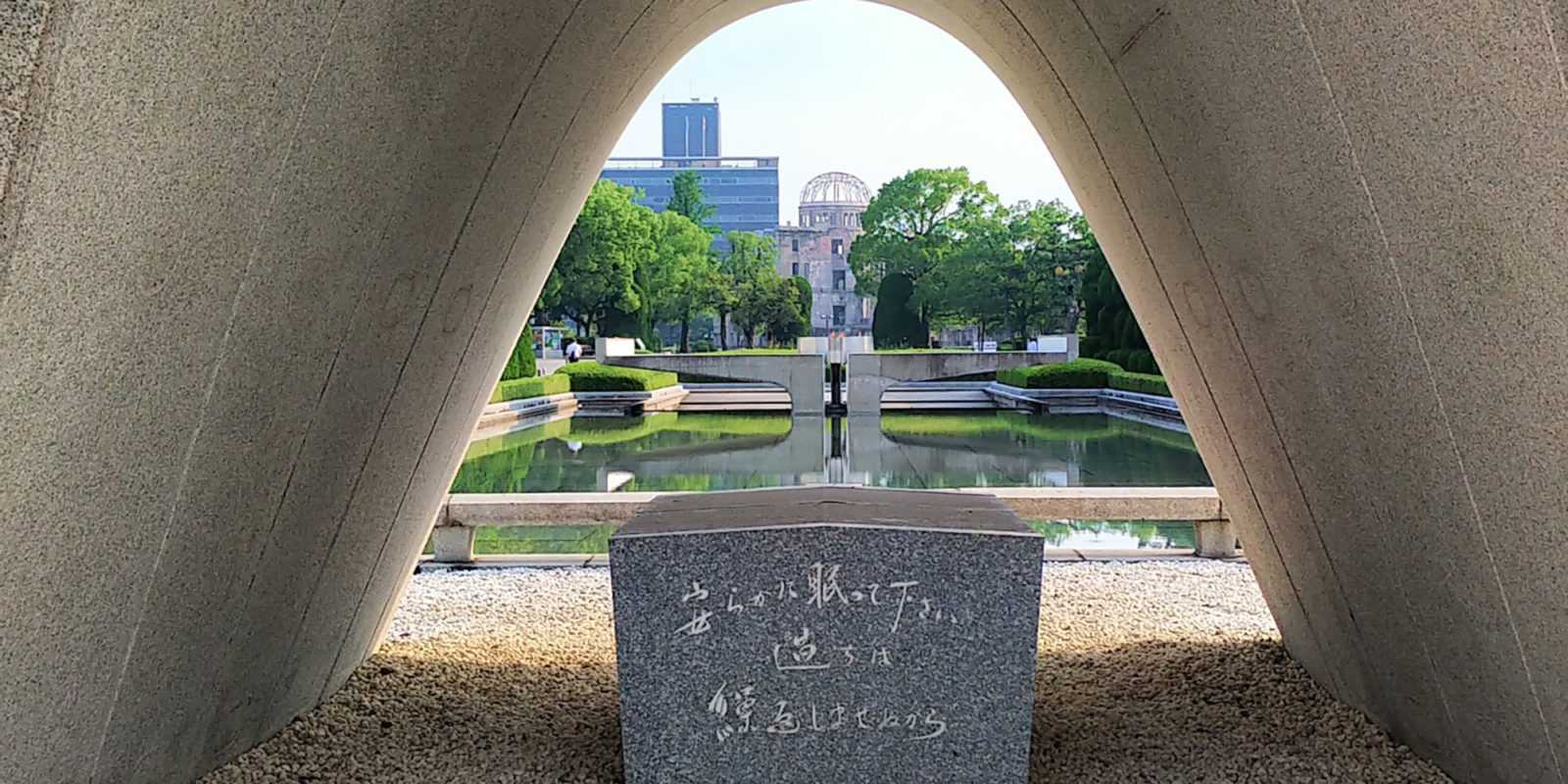

When the atomic weapon known as Little Boy exploded about 600m above Hiroshima on the morning of 6 August 1945, a group of children had just assembled in the schoolyard of Honkawa Elementary School, less than 500m from the hypocentre of the blast. They were awaiting roll call before their school day would start.

Except that it never would, as nearly 400 of them would die when, at 8.15 that morning the course of the world was changed forever.

The Hiroshima Memorial Museum displays pieces of their incinerated clothing. Those who weren’t killed immediately died slow deaths of pain and illness. Burnt by the intolerable heat of the explosion, which caused ground temperature in the city to briefly rise to 4,000°C, some drank the sticky, black rain that fell from the sky. The rain was radioactive.

On the surface, the lesson from Hiroshima is that the world should never, ever again experience nuclear warfare. But if you look closer, the lesson is rather that humans have the capacity to annihilate themselves. And we fail to heed this lesson at our peril.

Hiroshima’s average temperature has increased by 2°C since the 1930s. For reference, two degrees – if felt at a global scale – is considered by climate scientists to be the difference between normality and all of the world’s coral reefs dying, 70% of the world’s coastline being exposed to severe sea-level rise, and markedly more natural disasters.

Already, residents of Hiroshima complain of hotter and longer summers (temperatures were nearly 40°C this summer), coupled with – for the first time in living memory – torrential rains, like the storm that flooded the prefecture in 2018, killing 60 and damaging hundreds of homes.

Kyoto, about 300km from Hiroshima and the site of the landmark Kyoto Protocol of 1997, holds a hint of promise – along with a stern warning of what’s to come.

The first international agreement of its kind, the Kyoto Protocol on climate change came into force in 2005, the point at which it was ratified by at least 55 members who accounted for 55% of global CO2 emissions.

It signalled a global awareness of the fact that greenhouse gases emitted by humans (and not “naturally occurring”, as was believed before) were principally responsible for the gradual heating of the Earth and increased incidence of natural disasters.

While signatories to the protocol managed to reduce their CO2 output significantly, global emissions have increased by about 40% since Kyoto. Much of this is down to two prominent non-signatories: the US and China.

China has sustained its incredibly high growth rates for more than 30 years by going from one large infrastructure project to the next. Nothing exemplifies this like its record of commissioning the equivalent of two 600MW power plants every week.

Erdaoqiao, a settlement in south-west China, made headlines in 2015 for being the last village to receive power under China’s plans for nationwide electrification. This programme has seen electricity reach 900 million people since 1949, much of it in the last 30 years. (By comparison, Africa increased its electric power capacity by less than 1,000MW per annum on average between 2000 and 2018.)

It’s not just about power. China’s growth has been driven by the mass movement of people from rural areas to the cities. More than 600 million people have been urbanised and their productivity increased from 0.5% to 3.8% per annum and incomes by 8.5% annually, from $307 in 1978 to $2,381 in 2017.

To accommodate them, and enable this productivity increase, China has invested massively in infrastructure. Its cities are testament to this extraordinary development, changing shape and structure continuously. To do so, China consumed more cement in the three years from 2011-13 than the US did in the entire 20th century. In 2017, China produced more cement than the rest of the world combined.

But, growth that is largely infrastructure- and consumption-driven, is capped by physical limits – whether the continued availability of natural resources, population growth, continued increases in disposable income, or the allowances China sets itself in terms of carbon emissions. Already, the Chinese government’s push for cleaner development has increased the price of cement.

But, when China’s own resources have run out, and its domestic consumption and population growth (the latter already a cause of great concern to the government) have slowed, it will have to turn to other sources of growth. This might explain its fast-growing presence in Africa and the push behind the Belt and Road Initiative.

There is an environmental downside to such consumption-fuelled growth. While not as bad as India, which has the seven most air-polluted cities worldwide, China has 60 of the world’s 100 worst. This much was acknowledged by President Xi Jinping in professing: “Clear waters and green mountains are as valuable as mountains of gold and silver”, a theme he first picked up on in 2005 as party secretary for Zhejiang.

China’s lights – and its industry – are kept on primarily by coal, which supplies 70% of its energy needs, making China the world’s largest energy producer from coal – and there are plans to increase this by a further 20%. This does not mean China is stuck on this path, to the contrary, it can lead global change. To do so it will have to manage vested interests, such as in the construction sector and related industries.

China emits more carbon than the US and the countries of the European Union combined. It is fraught with paradox. Even though it is still building coal-fired power plants, it is the world’s largest investor in renewables and has the largest solar capacity. Renewables comprise one-quarter of its energy mix, most of which is from hydro. Radically changing this mix will require altering consumption patterns, especially in China’s burgeoning cities, which produce an estimated 85% of the country’s emissions. The country overall creates more than 27% of the world’s total emissions.

No country has, in living memory, made a bigger, positive impact on poverty and global growth. No country can make a bigger impact on climate change if it were to get renewables right and reduce its carbon emissions.

Africa has similar needs to China and much of East Asia during the last century in terms of energy provision and infrastructure shortages. But Africa’s realities are different, and so are the times.

The technology available today offers alternatives to the resource-intensive, coal-power model used by China and others before it. The absence of national grid infrastructure for central power transmission in most African countries apart from South Africa means that decentralised or mini-grid solutions are a natural preference.

East Asian countries are increasingly turning to renewable, off-grid solutions to bridge this rural-urban gap. Myanmar, which has one of the lowest electricity penetration rates amongst ASEAN member states at just 26%, has embarked on a rural electrification programme using solar energy to supply electricity.

The Myanmar government aims to generate 30MW each from off-grid sources to power some 500,000 households in the first five years of the programme, which started in 2017.

Cambodia aims to connect 70% of households to the national grid by 2030, has similarly adopted a master-plan to facilitate rural electrification. This promotes the development of mini-grids that utilise solar home systems, small hydropower and solar photovoltaic systems in rural areas.

Technological advances in renewable options like solar are useful for increasing access, such as for rural consumers in sparsely populated areas, but less so for industrial-size projects that create jobs, or for densely-populated cities.

There is also an imperative to make full use of potential resources. According to the World Bank, 40% of Africa’s output reaches its potential customer market due to problems of distribution and transmission. In Nigeria, 28% of electricity is “lost” between the generator and the customer, not to mention seven idle power stations.

Africa harnesses just 7% of its hydro potential, compared to 65% globally. The continent has vast stores of untapped sun and wind potential. There are few compelling reasons to go the route of China, especially as that will seriously jeopardise future inhabitability of the planet.

According to John Cook of the Centre for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, four Hiroshima-bombs worth of heat is released into the Earth’s atmosphere every second as a result of human industrial activities, most of which is absorbed by the oceans.

The lesson from Hiroshima is that if we do not stop this, we will kill ourselves, not in a blinding flash of light, but through a no less deadly if less dramatic process.

This article originally appeared on The Daily Maverick.