News

The Monkey and the Grenade: How the Crisis in Ukraine Ends

Unlike South Africa, Ukraine's basic services keep functioning despite it being in the midst of an all-out war. The power stays on and the trains keep running, whatever the Russians throw at them. There are huge tailbacks at the borders, but this illustrates at least as much an economy hungry for trade and frustrated by the closure of its Azov and Black Sea ports as it is border and logistics inefficiency.

"We are fighting for our country and Western values,” explain Ukrainians. “And we won't stop.”

More than anything, it is this sense of patriotism and resourcefulness — and a little bit of help from Ukraine's friends — that is likely to determine the war's outcome.

The British spy George Blake, who defected to the Soviet Union, said just before his death in 2020 that spies now have “the difficult and critical mission” of saving the world “in a situation when the danger of nuclear war and the resulting self-destruction of humankind again have been put on the agenda by irresponsible politicians. It's a true battle between good and evil.”

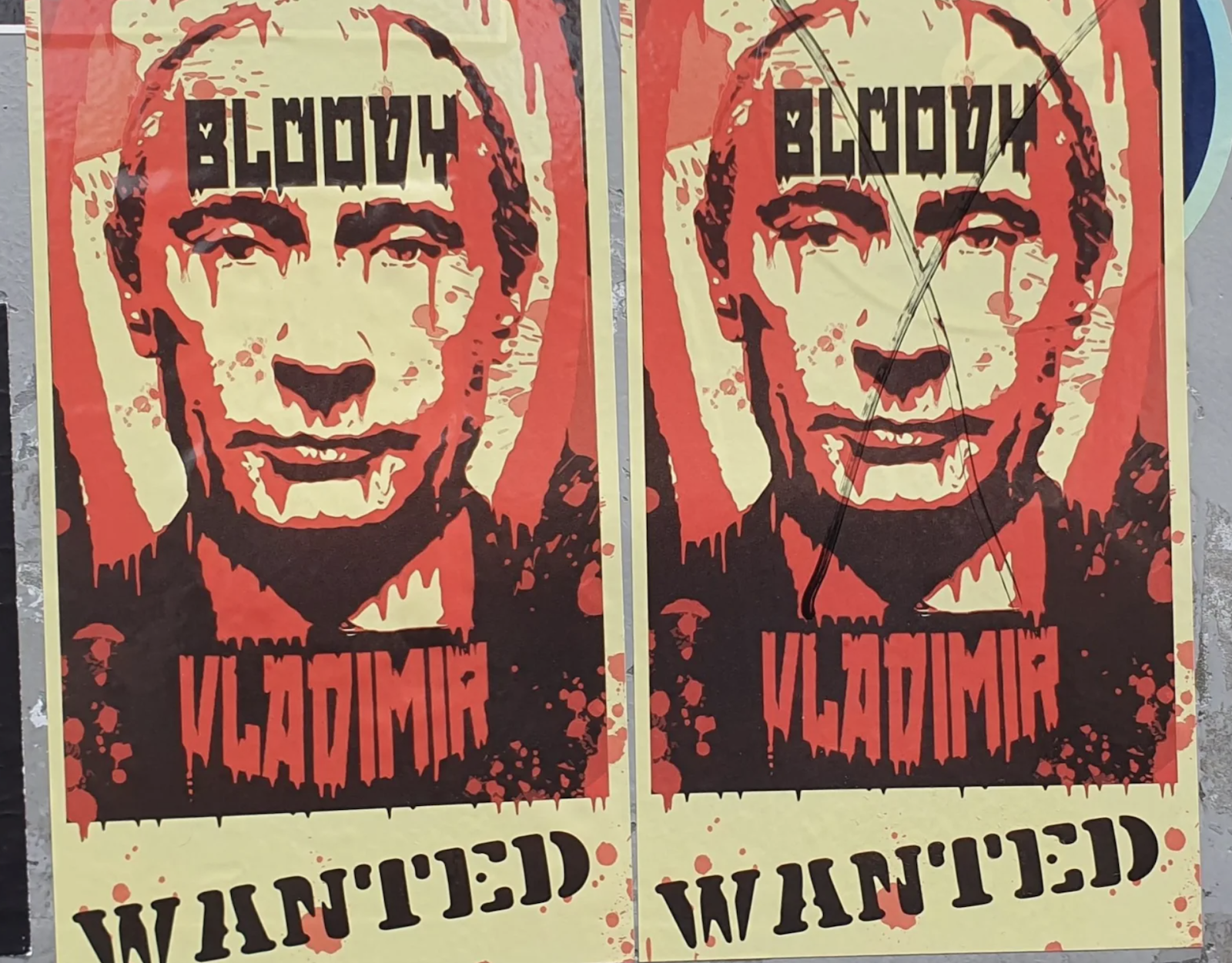

Blake, who went over to the Russian side while a prisoner during the Korean War, may have inadvertently been describing Vladimir Putin's irresponsible assault on Ukraine.

Unless the Russian leader wanted another Cold War, he has (so far) failed dramatically in strategic terms: first, in his aim to “liberate” Ukrainians from their government, and second, to curtail Nato's enlargement.

With Finland and Sweden joining, he now has a much larger Nato on his borders — a 1,340km longer Nato, to be precise. He has ignited a fierce Ukrainian patriotism.

I have driven through more than 3,500km of Ukraine north to south over the past three months: there is scarcely a building without Ukrainian flags, banners, posters and painted walls.

How might this war end?

The presence of such nationalism, shaped by the anvil of conflict and genocide under the Holodomor perpetrated by Stalin in the 1930s — in which millions of Ukrainians died of starvation due to the confiscation of their wheat — reduces the scenario options.

Those scenarios, which have Russia maintaining control over all or some of the roughly 20% of Ukrainian territory now occupied, can only be temporary — the conflict frozen, but unresolved.

The challenge for Ukraine is not only in stopping Russia grinding out its advances — for which heavier precision Western weaponry is required — but finding the means to remove them.

Unlike Russia, which has simply destroyed the cities targeted, such as Mariupol and now Severodonetsk, Ukraine's counterattacks have to be tactically more astute and avoid civilian damage and casualties — it's their own people and country, after all.

This outcome is not entirely down to Nato assistance, of course, but depends also on Russia's economic and military strength.

The signs are not hopeful, given the claimed Russian military losses — 30,000 troops, 1,500 tanks, 2,500 armoured vehicles, more than 500 aircraft and 600 drones — which are expensive and time-consuming to replace, not least because of the skills required.

This will test the Russian economy, even if you believe the Russian media's claim that it's thriving due to a higher oil price.

At between $2-million and $5-million a pop for a tank, and at least 15 times for a fighter aircraft, war is expensive — and that is before Western sanctions begin to bite, which they will by the end of this year when Europe has committed to cut off Russian oil imports, a principal export earner.

To some extent, the outcome depends on how the region works with Ukraine to get its trade routes for its commodities back up and running, including through Moldova, Romania and Poland especially.

It will also rely on what the world has learnt from Putin.

There will inevitably be those who call for appeasement, even though the record of feeding such authoritarians chunks of other people's territory is seldom a formula for a durable peace.

Until now, Putin has successfully portrayed himself as a man who will stop at nothing, an irrational actor — “a monkey with a grenade”.

But this is a tactic designed to keep the West guessing at his unpredictability, especially over the use of nuclear weapons. Equally, when Russia decides to disengage — such as it did in redeploying its forces from around Kyiv in April or more recently from Snake Island — there was no monkeying around in the orderly and efficient withdrawal.

But the West, too, possesses nuclear weapons. Deterrence is as much about politics, staying power and signalling as it is about hardware.

Nato's problems have stemmed from its disparate organisational and political complement, though for now the differences in approach between its members are smaller than at any time in the post-Cold War order.

And to the greatest extent, the outcome depends on the extent of Ukrainian fighting spirit and political will.

For the moment, President Volodymyr Zelensky's approval ratings are over 80%. Whether this support will flag the longer the war drags on and the costs mount, or whether Ukrainians will further harden their position towards Russia as a consequence, remains to be seen.

For now, most Ukrainians are not interested in compromise. They demand compensation and justice.

It seems that this war will not end — conventionally or through a long-term insurgency — without a complete Russian withdrawal from Ukrainian territory. Those terms are, after all, what most countries would expect.

The human cost of the conflict thus makes a deal trading land for peace politically very difficult for Zelensky, no matter his obvious skills. After all, it is Ukraine that has been invaded.

The recent history of eastern and central Europe suggests that this occupation will, no matter the Russian propaganda, be bloody but temporary.

This article originally appeared on the Daily Maverick