News

The Careless State: Using 'easy money' to retain power, pursue vanity projects and cushion the elite

A key difficulty to understand the point at which states fail their citizens is in the criteria — when exactly is a state fragile or failed?

Former Research Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Former Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Failed, fragile, weak, collapsed, vulnerable, moribund, straggling, struggling, crisis, quasi-failed, “non-state”, broken, invisible, insufficient, stillborn, phantom, or even Potemkin states (those that pretend to work, but don't), have all been put forward as models of state dysfunction.

A key difficulty to understand the point at which states fail their citizens is in the criteria — exactly when is a state fragile or failed? There appears to be no single reason or a tipping point at which a state becomes officially “failed”, an imaginary dividing line between success or normality and failure. Countries, after all, exist on a spectrum or continuum rather than in a binary world of success or failure.

Economic growth and per capita income figures are an expedient shorthand to identify poor and weak countries based on their trajectory and absolute levels. Fragility is in this respect an indicator of future failure. By itself, poverty is an imperfect measure of fragility, since many of those classified by some as fragile are middle-income. For the same reason, poverty does not necessarily result in radicalism and terrorism. Iran and Saudi Arabia are, after all, not poor.

A general problem with statistics, whatever their reliability (and statistics are often a first casualty of weak governance), is that they ameliorate the extremes. What does an “average” life expectancy in Angola, for example, convey about the prospects of longevity for a young child born into Luanda's musseques, or slums? What can GDP per capita inform us about the reality of wealth divides in terms of access to education, healthcare and finance, the sum of future prospects?

Countries that work for some, at least for the relatively well-heeled visitor, can work against the locals. Think Kenya. There are those that significantly and continuously underperform, lurching from crisis to crisis — a roller coaster of political and economic collapse— but do not explode into violence and thereby become the focus of international aid groups or humanitarian assistance, one external metric of failure. Think Argentina.

Countries can contain both elements of perfect functionality and failure for different communities; indeed, some constituencies prosper under conditions of failure. Failure can occur in terms of extreme violence. Some fail because they can't deliver what their citizens had hoped for or expected.

Failure is more pronounced as expectations rise: the provision of basic security is one thing, a house, education, job and a car is another. Sudden falls in income can provoke failure.

Attempts have been made to provide an empirical basis for these “fragility” classifications. The Failed States Index of the Fund for Peace, for example, has ranked countries for two decades using a complex methodology based on quantitative and qualitative data, and reporting across four areas: cohesion, the economy, political and social. These incorporate sub-sectors such as security, state legitimacy, demographic pressures, human rights and the rule of law, human development and skills flight, inequality and the risk of external intervention, among others.

"There are those that seek to maintain weakness to be able to profit, a deliberate choice, a course of action assiduously pursued regardless of the consequences for many citizens. Mobutu Sese Seko is one who did this."

Yet rankings and labelling of fragility are resisted by the very states they seek to describe on the grounds that they know more about their domestic circumstances than outsiders. The very notion of a “failed” state itself has been rejected by some since it “implies no degree of success or failure, no sense of decline or progress… a binary division between those countries that are salvageable and those beyond redemption, says The Guardian.

“It is a word, reserved for marriages and exams.”

The terminology is rather “like Jabba the Hutt after a night at an all-you-can-eat pizzeria: broad and ill-defined”.

Jokes aside, the terms fail to reflect the role and intentions of leadership. As former president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who led Liberia magnificently from the ashes of decades of war from 2005 to the point where the west African nation — an archetypal failed state when she came into office — could contemplate a development take-off a decade later, puts it: “Fragile states do not lack the political will to achieve sustained growth.”

Put differently, more interesting than the output, are the inputs into the creation of a pathology of failure. The confusion of definitions and terms does not help, much, in the quest to understand why states fail their citizens, what can be done to avoid it, and what one might do to help them out of this state once they fall into it.

The abiding commonality for states on this spectrum of failure is that they fail their citizens while usually enriching their elites. They work well for a small, select group of individuals. They are more careless than fragile, and perhaps fragile because they are careless. While the notion of being a failure implies a certain apathy and helplessness, of “state victimhood”, to the contrary it may precisely be intended to bring about this “state of being”.

What could be the criteria for such “careless states”?

These are those countries whose leaders promise but seldom deliver. The key here is the seldom bit. Most leaders overpromise, because that's the nature of the political game. But some do so cynically, with absolutely no regard for delivery. Outgoing US President Donald Trump is one. But there are many others in Africa who make him look like an amateur.

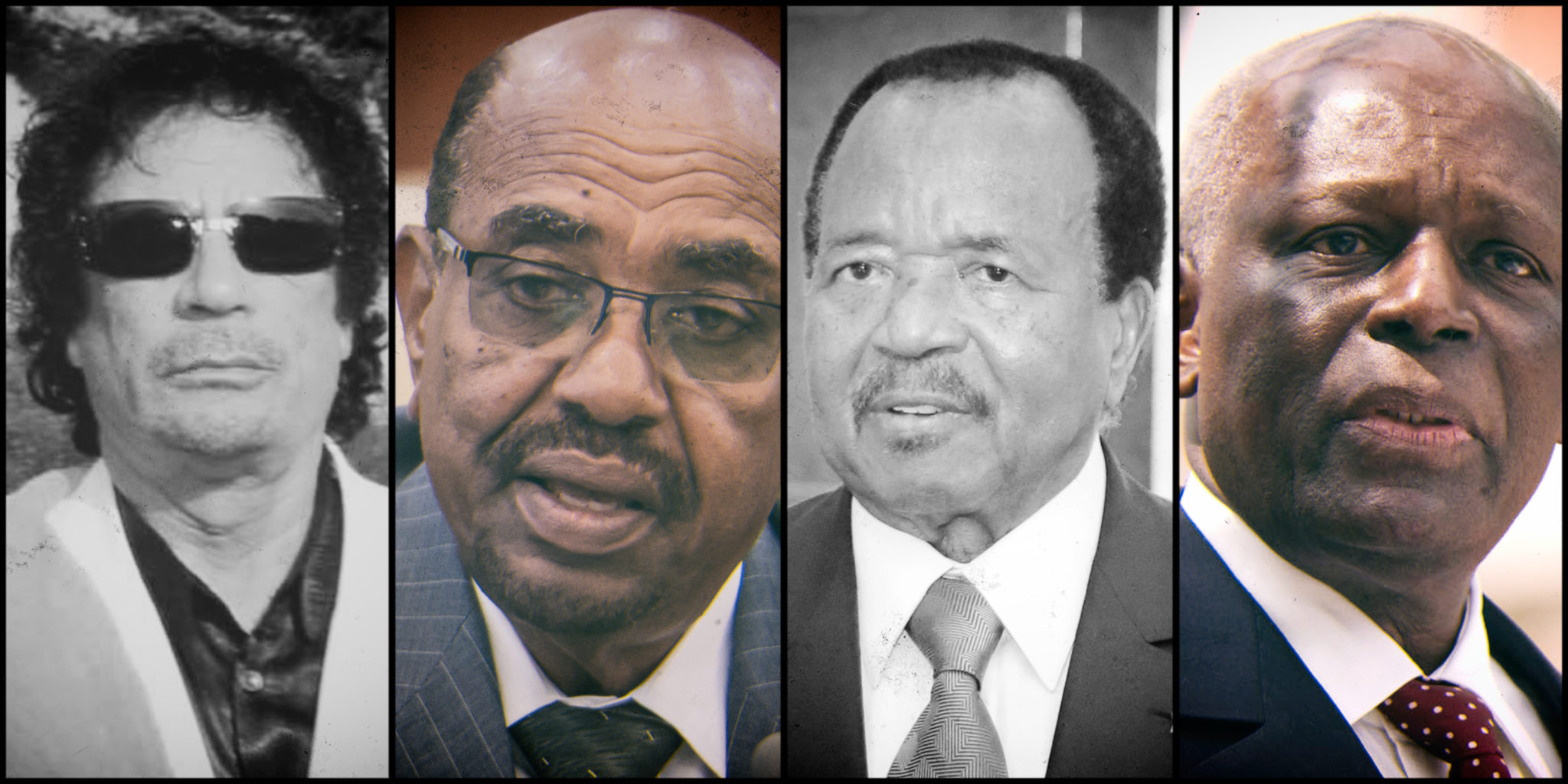

Careless states are also those that don't turn the revenue accrued from enormous natural resources — oil, for example — into endowments to development, as Norway has done so spectacularly with oil. Rather, they use this “easy money” to pursue war, vanity projects, or just simply pump it into the pockets of the elite. There is a tragically long list here, especially in Africa: Nigeria, Angola under the José Eduardo dos Santos kleptocracy, Omar al-Bashir's Sudan, Paul Biya's Cameroon… there are too many to isolate the typology.

Then there are those that care more about ideology even in an era when most seem to appreciate that the free market usually produces the goods, at least more so than the alternative. Fortuitously, such ideological interventions can be used to diminish space for the private sector, to enable the sort of “captured” deals for which the Zuptas became famous.

There are those that simply care about raw power — how they can retain it, wield it, and export it. They may be economically illiterate (Hugo Chavez and his dullard Venezuelan successor Nicolás Maduro, or Robert Mugabe) if politically smart, or manically messianic (think Muammar Gaddafi). They deliver goodies to varying degrees, but eventually the system invariably eats them as they run out of options.

There are those that seek to maintain weakness to be able to profit, a deliberate choice, a course of action assiduously pursued regardless of the consequences for many citizens. Mobutu Sese Seko is one who did this.

And there are those — the most regular sort — that maintain the pretence of political normality of the uberconcerned state. They are constantly scheming and manoeuvring, not in the interests of power per se, but for profit, with transactions at the fingertips, thinking of self before state, of PPE contracts, of the maintenance of a path of fiscal expansion. These are the men and women cementing the priority of person, party and people, and in that order.

There are huge and immediate costs to such carelessness. This is a short-term game, certainly when measured in the economic history of nations. While these extractive methods might benefit different groups for a short while, the transaction costs are ultimately as ruinous for the privileged elites as they are for the general populace.

So, what to do?

In an earlier, certainly more chivalrous if sexist, age, women and children left the sinking ship first, the captain last, if at all. At Sandhurst, even today, officer cadets are taught to look after their animals and men before themselves. Simon Sinek, the communications guru, says that real leaders eat last.

And to turn it on its head: how might we ask leaders to convince us that they are not, indeed, careless?

One key measure of a state which is not careless in the Covid-19 era could be when real leaders vaccinate last.

This article was published by The Daily Maverick.