News

South Africa’s 2024 Election Holds Key Lessons for Democratic Maturity in Africa

The maturity of democracy hinges on the active participation of an informed electorate, the integrity of the electoral process and the willingness of political leaders to collaborate for the common good.

The recent South African election has provided a profound illustration of the strides made in democratic maturity and the evolving power of the people’s vote.

As Ghana prepares to execute its ultimate demonstration of democracy – elections in December 2024 – it is essential to draw lessons from South Africa’s experience. Here, the key takeaway is the increasing belief in the value of the vote and its potential to effect change and accurately reflect the electorate’s preferences.

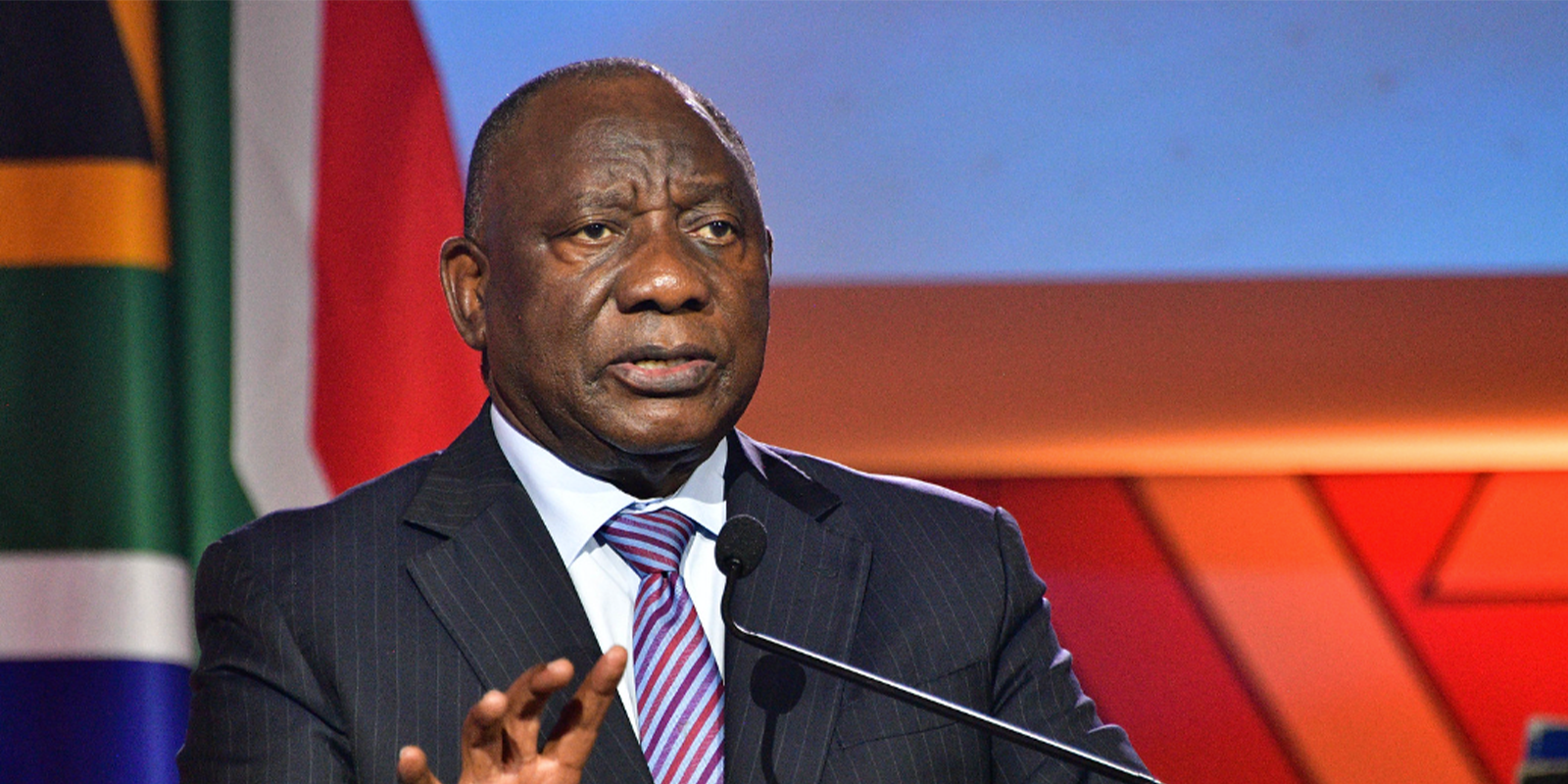

In his speech following the election, President Cyril Ramaphosa emphasised his country’s democratic evolution:

“What this election has made plain is that the people of South Africa expect their leaders to work together to meet their needs. They expect the parties for which they have voted to find common ground, to overcome their differences, to act and work together for the good of everyone.

“Our people expect all parties to work together within the framework of our Constitution and address whatever challenges we encounter peacefully and in accordance with the prescripts of our Constitution and the rule of law.”

Ghana today

Since its democratic transition in 1992, Ghana has been hailed as a beacon of democracy in West Africa, making significant strides towards consolidating democratic principles.

Since democratic rule was restored in 1993, the country has held seven free and fair elections, accompanied by peaceful transitions of power between opposing political entities on three occasions (2001, 2009 and 2016).

Through its multiparty elections, improvements in human rights, and the independence of key institutions such as the Electoral Commission, Ghana has showcased its commitment to fostering a liberal democratic culture.

However, amidst these successes lie challenges that threaten to undermine the country’s democratic progress.

Key among this is the elite capture of democratic institutions.

As political scientist Emmanuel Gyimah-Boadi points out, despite Ghana’s achievements as an electoral democracy, a select cadre comprising government officials, political factions, senior bureaucrats, media moguls, influential personalities and private sector entities have methodically co-opted the benefits derived from democratic governance.

Examples of this arise in political interference in the leadership of the Electoral Commission – a challenge which always raises concerns about impartiality and undermines public trust and yet falls on deaf ears by leaders.

Also, winner-take-all politics threatens to deepen polarisation and undermine national cohesion. The dominance of two major political parties, the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP) perpetuates a cycle of clientelism and patronage, sidelining smaller parties and independent voices.

What this shows is that democratic maturity is not a once-and-for-all outcome. Beacons can decline in performance. Greed, partisanship and personalisation of politics can chip away at the most remarkable democratic gains. In the quest to safeguard these systems of governance, we need to learn from people who seem to be doing some things right.

The power of the vote

The May 2024 elections in South Africa highlighted several critical lessons about democracy in action. The ANC, which had dominated the political landscape for three decades, was held accountable by voters dissatisfied with its performance.

This electoral outcome underscores a fundamental principle of democracy: the capacity of the people to decide who will best serve their interests.

The ANC’s significant reduction in support, from a historical dominance to around 40%, signifies a shift towards a more competitive and dynamic political environment where votes truly matter.

Key takeaways for Ghana

- Belief in the power of the vote: The decline in support for the ANC demonstrates the electorate’s willingness to hold parties accountable. Democracy offers us the ability to decide who we think will best run the country in our interest. Ghanaians, dissatisfied with the status quo, and the political duopoly of the NPP and NDC, can learn from this. There needs to be significant investment by civil society organisations and outsiders to promote voter education and encourage active participation. When citizens understand the impact of their vote, they are more likely to engage in the democratic process, demand accountability and contribute to good governance.

- Finding common ground for the good of the nation: South Africa’s election results have set the stage for coalition talks, highlighting the importance of political collaboration. President Ramaphosa’s call for parties to work together for the common good illustrates the necessity of coalition-building in a fragmented political landscape. Ghana can benefit from fostering a political culture that emphasises policy over personality, helping voters make informed choices that lead to stable governance. Indeed, while the situation may not be the same, Ghanaian political leaders can learn from this by encouraging political parties to find common ground and work together, especially in times of political fragmentation and growing populist demagogy. The best outcomes, it has been said, occur when both sides in a conflict are left equally dissatisfied.

Challenges and opportunities

Despite the positive aspects, the South African election also revealed some challenges that Ghana must address to strengthen its democracy:

- Participation crisis: Voter turnout in South Africa hit a record low, with just over 40% of eligible voters participating, down from 86,8% in 1994. Although a part of this stemmed from not-so-great management of the voting day activities by the Electoral Commission, this apathy presents, for the most part, a crisis of legitimacy for democratic institutions. Ghana, on a similar path with voter turnout, must work to increase voter engagement by addressing disillusionment with the political process and improving the management of elections to ensure they are efficient and accessible and deemed a worthy civic activity amidst competing interests.

- Combating disinformation: The election, as with many across the world, saw a surge in disinformation campaigns, particularly on social media. These campaigns often involve extreme and sometimes crude messaging meant to sway voter behaviour. Ghana – political and civil society alike – must be vigilant in combating misinformation by promoting media literacy, avoiding inflammatory rhetoric which is hard to come back from, and ensuring that accurate information is readily available to the public.

Building a stronger democracy in Ghana

The lessons from South Africa’s May 2024 election are clear: the maturity of democracy hinges on the active participation of an informed electorate, the integrity of the electoral process, and the willingness of political leaders to collaborate for the common good.

This means that encouraging voter education, enhancing electoral (commission) integrity, promoting political cooperation, and empowering civil society are crucial steps towards achieving a more robust and resilient democracy.

The excerpt from Ramaphosa underscores a crucial aspect of democratic maturity: the expectation that elected leaders, irrespective of party affiliations, must collaborate for the common good. This principle is not only a hallmark of a mature democracy but also a necessary condition for political stability and effective governance.

By learning from and applying these principles, Ghana can strengthen its democracy and ensure that the power of the vote is truly reflective of the people’s will.

This article originally appeared on Daily Maverick.