News

Remembering the DDR - No Joking Matter

Despite a fresh nostalgia for the DDR — so widespread it's known as Ostalgie — history is forgotten at our peril.

The gallows humour about life in the former East bloc is legend.

A citizen is sent a letter informing him that he is lucky enough to receive a Trabant, the archaic car produced in East Germany. The salesman tells him to come back to pick it up in 11 years. “Shall I come back then in the morning or the afternoon?” the lucky customer asks. The salesman replies: “Why do you want to know that? It’s only in 11 years’ time.” The customer responds, “I would prefer the afternoon; the plumber is coming in the morning.”

The small, plastic Trabant, known as the “spark plug with a roof”, with antiquated styling and smoky two-stroke engine (said to be 12 metres long – two of car and 10 of smoke), has obtained cult status today. But it is a symbol of what went wrong with the German Democratic Republic, better known as the GDR, DDR, or East Germany, and why, for all of the revisionist mythology, it was a crap system.

The DDR came about in 1949, the creation of a country out of the territory occupied and administered by Soviet forces at the end of the Second World War. It ended with German unification in October 1990 following the fall of the Berlin Wall in November the previous year.

The DDR collapsed because its economy, touted as one of the most robust in the Soviet bloc, failed to produce what its citizens wanted. It was said that East Germany’s economy was like an old steam train, but unfortunately 90% of it went through the whistle.

The state was incapable of making efficient decisions about allocation – of jobs, skills, resources, pricing and products. Prices were set by government, not through the pressures of competition, supply and demand.

This reflected other problems. For one, there was no political competition. The DDR was effectively a one-party state, governed by the Socialist Unity Party (SED) through an alliance organisation, the National Front of Democratic Germany.

Another was the failure to invest enough in higher education, and in R&D. Unable (or unwilling) to give a value to intellectual property, in a centrally planned system conformity and obedience were encouraged at the cost of innovation. The underpinnings were there from school, however, where the emphasis was on rote learning.

Personal incentives were few and far between. The country’s pay scales did little to encourage hard work or maximise personal potential. Whereas a professional engineer, with 10 years of training, would receive a monthly salary of 1,470 Ostmark in 1988, a bricklayer, with just two, would earn 1,370. By comparison a television set would cost 4,900 Ostmark, and rent just 109 Ostmark for a three-room flat.

Unsurprisingly for a country where the national emblem consisted of a compass (for the working intelligentsia) and a hammer (the working class) encircled with rye (the peasant), and the motto was “workers of the world unite”, private enterprise was actively discouraged. Land was seized and organised into collectives. The industrial sector, employing 40% of the workforce, was nationalised into “People’s Enterprises”, or VEBs. While mass accommodation was provided, these prefabricated Plattenbau (from “platte”, or slab) were bleak by comparison to the offerings of the West, where average income was twice as high.

The fabulous DDR museum under the shadow of East Berlin’s landmark television tower near Alexanderplatz illustrates these problems.

With subsidies, basic goods cost next to nothing and were abundant, so much so that people fed bread to their pigs. But the hunt for scarce items including fruit and even toilet paper was a central feature of life in the DDR, similar to contemporary Venezuela. Among the jokes collected and filed by the West German intelligence service to provide an insight into political conditions was, “Did East Germans originate from apes?” The answer: “Impossible. Apes could never have survived on just two bananas a year.”

The lack of investment in people and products took a toll. East Germany was dependent on outside raw materials for its manufactures, and exports for cash to buy them. In a vicious cycle, these export goods, from Praktica cameras to the venerable Wartburg and Trabi cars, were outdated and badly built, receiving rock-bottom international prices. Instead of fuelling the economy, this caused foreign debt to increase 25 times during the 1970s, while the collapse in oil prices meant that the Soviet Union could also no longer afford to subsidise its client states at previous levels.

By the late 1980s, despite attempts to reorganise and restructure under various “new orders” and “five-year plans”, the DDR system braced for inevitable collapse. The country was so cash-starved at one point that it exported cobblestones.

In essence, when those in the West could buy Golf GTis, their cousins in the East were lucky enough if they got a Trabant.

In the end, consumerism triumphed over communism. Far from being the bulwark against Western influences, the economy proved the Achilles’ heel of the system, as East Germans voted with their feet and cash. Those with access to foreign exchange could buy goods at Intershop, which had high-quality goods. For example, a pair of Levis became sought-after as a sign of hip Western consumerism, even though they sold for a quarter of the average monthly salary.

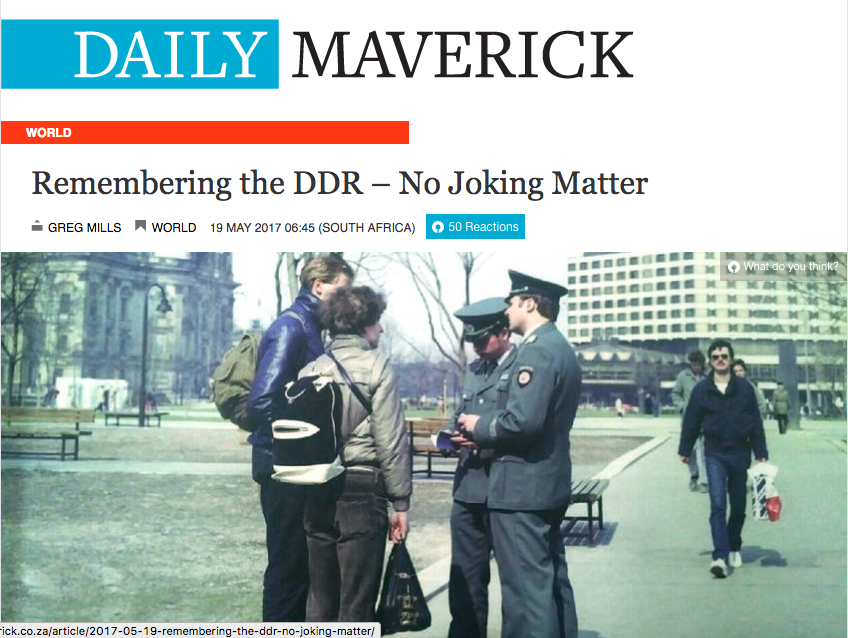

For those still hankering after a similar system, it should be reminded that this lack of choice was possible due to the absence of freedom; and that was brutally enforced by a pervasive security structure.

A bleak complex of clad concrete buildings at Haus 1 on 103 Ruschestrasse off Frankfurter Allee in the area of Berlin-Lichtenberg housed the Ministry for State Security, commonly known as the Stasi. Its members saw themselves as an omnipotent elite group of “first-class comrades” serving “the dictatorship of the proletariat”, referring to each other as “Chekists” in following the tradition established by the Bolsheviks in 1917 when they created a secret police known as the “Cheka”.

By 1988 the Stasi employed a vast network of more than 90,000 agents and at least 189,000 “unofficial collaborators” (though the total of “information providers”, or Auskunftspersonen, is estimated to be over two million) to keep tabs and files on the DDR’s citizens. East Germans expected their mail to be steamed open and conversations to be bugged. Certain social groups, from punks to churches, received special attention. And they didn’t just infiltrate and monitor, as the prison at Berlin-Hohenschönhausen with its 103 cells and 230 interrogation rooms, now a Stasi memorial, reminds. More than 72,000 were jailed for trying simply to leave the Republic, of an estimated 250,000 political prisoners over the four decades of the DDR.

Two months after the fall of the Berlin Wall, demonstrators invaded the Stasi building to prevent the destruction of an estimated one billion pages of files, most of which were preserved and are now publically available. The Stasi assembled “F16” card files on 5.4-million people, which were supplemented by the “F22” explaining why they took an interest.

Fake news and Photoshop would be more modern equivalents. Stasi methods are as tempting now to those instinctively authoritarian as during the Cold War, a process made easier by digital telecommunications monitoring and interception.

Mielke summed up the purpose of the Stasi in a speech to the Central Committee in April 1981 as a “constant effort to clarify ‘who is who’ … to identify people’s true political attitudes, their way of thinking and behaving … providing an answer to who is the enemy; who is taking on a hostile or negative attitude; who is under the influence of hostile, negative and other forces and may become an enemy; who may succumb to enemy influences and allow himself to be exploited by the enemy; who has adopted a wavering position; and who can the party and state depend on and be reliably supported by?”

Despite the menace, East Germans made light of this, inevitably. “Why do the Stasi work together in groups of three?” they asked. “You need one who can read, one who can write, and a third to keep an eye on the two intellectuals.”

Jokes thrive in dictatorships, a means of bringing leaders down a peg or two. But there were risks, given that the Stasi was tasked to consider every political joke as a potential threat and its teller liable for prosecution.

Despite its reputation for effectiveness, the system collapsed quickly. Mielke, who had served as its chief for 32 of the DDR’s 41 years of existence, and was known as the “Master of Fear”, was booed and jeered from the newly emboldened DDR parliament, or Volkskammer, to which he had been summoned to justify his role on 13 November 1989, four days after the Wall fell. Mielke’s attempts to convince his audience of the “triumph” of the socialist economy were laughed at, while he was formally rebuked over his continuous use of the term “Comrades” to address members.

If the Stasi were the (mostly) invisible hand of the state, there was a constant physical reminder in the form of the Berlin Wall. Before the Wall’s erection, 2.7-million East Germans had left for the West. But that did not stop the rot. Low birth rates saw East Germany’s population decline to 16-million by 1990.

Critical thinking was resisted even in the arts. East German radio had a 60% quota of home-grown (or “brother-state”) music that it was required to play, with local artists encouraged to sing only in German. So long as the 39 East German newspapers, two television channels and four radio stations all had one point of view, the people’s response was to tune into West German television and radio.

The East Germans played their part in various liberation wars in Solidarität, as the official magazine DDR title on the subject had it. A special tax, up to 5.5%, bringing in over €15-billion a year, was instituted after reunification to generate funds from the richer West to rehabilitate the weaker East, goes by the same name.

The ironies don’t end there. The workers’ republic was eventually undone by its own population, the chant of the time “we are the people”, the words used by the poet Ferdinand Freiligrath about the 1848 revolution.

It was joked in the DDR that “Capitalism is the exploitation of man by man. What about socialism? Under socialism it is exactly the other way around.”

True perhaps, but without the choice and freedoms enabling efficiency, competitiveness and sustainability. Despite a fresh nostalgia for the DDR – so widespread it’s known as Ostalgie – history is forgotten at our peril. While the free market is not perfect, and business leaders everywhere should be encouraged to soften the bottom line in pursuit of social peace, it is, to paraphrase Churchill, better than all the other systems out there.

This article was originally published in The Daily Maverick.