News

Reducing Cross-Border Trade Costs will Increase Africa’s Competitiveness and Revamp Growth

As a percentage of total global GDP, cross-border trade in goods and services has nearly doubled from 1990 to 56%. For example, trade between China and Africa rose from under $1-billion in 1995 to over $120-billion in 2016. The world is increasingly one large, integrated market, a fact that no country can afford to ignore.

African economies are in danger of falling further behind their global competitors. Unless ways are found to radically improve trade between nations on the continent and with the world at large, they risk creating the foundations for a destabilising socioeconomic fabric and global crisis.

While alarming, we have every reason to be hopeful about the economic prospects of African countries, but only if the right choices are made now.

As the continent prepares for a pending population boom and a rapidly changing global economy, governments and leaders must abandon the old “business-as-usual” approach and embrace different strategies that will yield desirable and prosperous outcomes.

Can Africa step up or take advantage of this, in the process deepening the continent’s interconnectedness?

Africa, especially under the auspices of the free trade area objectives, will require a well-defined trade strategy that is symbiotic and functions both domestically and regionally, and one that makes it competitive with its outputs.

Setting up the right conditions – from political stability to clearly defined economic policy and complementary infrastructural development – will play a significant role in answering this question. Also, significantly, it will involve understanding the basics of things and doing them better than others.

The “Falling Long-Term Growth Prospects: Trends, Expectations, and Policies” report recently published by the World Bank offered thought-provoking discussions on the long-term potential output of global growth rates since the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

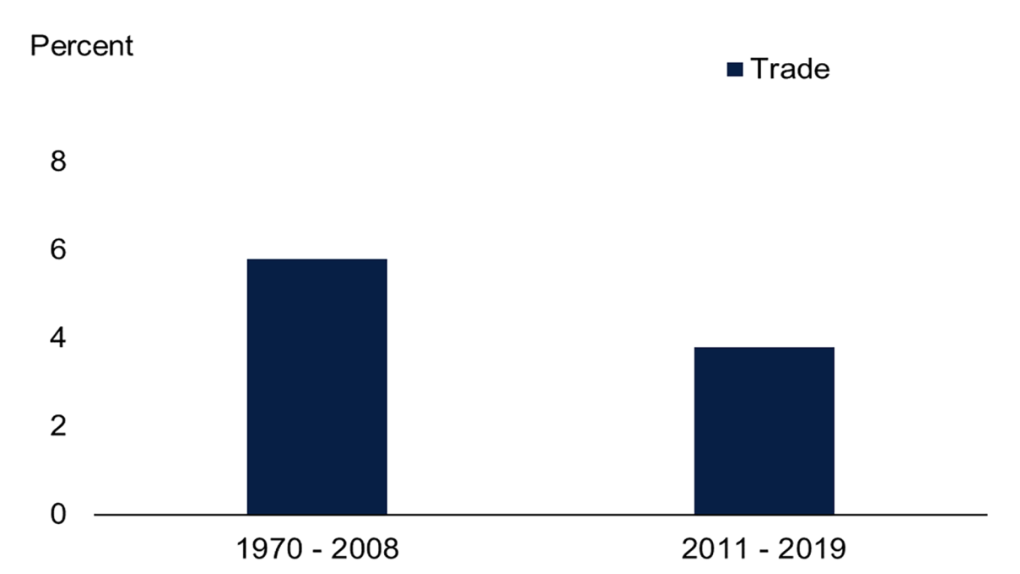

I especially found that the assessment provided under the heading “Trade as an Engine of Growth: Sputtering but Fixable”, co-authored by Franziska Ohnsorge and Lucia Quaglietti, captured the main topical issues shaping much of the concerns, challenges and opportunities around revitalising trade growth and deepening trade through global value chains and integrated regional trade.

Below are takeaways that accurately reflect existing challenges with trade and the requisite solutions:

Global trade remains one of the world’s most important economic growth tools. Recent research indicates that the liberalisation of trade can contribute significantly to economic growth, with estimates suggesting a potential increase of 1.0 to 1.5 percentage points and a resulting 10% to 20% rise in income over a decade.

Over the past three decades, international trade has generated a remarkable 24% rise in global income and a significant 50% improvement in income for the most deprived 40% of the population.

Furthermore, the economic growth facilitated by trade has helped more than 1 billion people escape poverty since 1990. Countries that embrace international trade and incorporate themselves into global value chains have enjoyed faster growth, greater innovation, and increased productivity, leading to higher incomes and more significant opportunities for their citizens. By integrating with the global economy via trade and global value chains, nations can reduce poverty and promote economic growth and prosperity at home and abroad.

As a percentage of total global GDP, cross-border trade in goods and services has nearly doubled from 1990 to 56%. For example, trade between China and Africa rose from less than $1-billion in 1995 to more than $120-billion in 2016. The world is increasingly one large, integrated market, a fact that no country can afford to ignore.

However, global trade growth has slowed due to recent global headwinds such as trade tensions between major economies and complications in global value chains. These occurrences have shown that existing trade patterns are heavily susceptible to minor shocks from even the world’s most remote but largely integrated economies.

That is not inherently bad. The challenges exist around the structural factors that supported rapid trade expansion in the past and have since matured or flailed.

Barring a significant policy effort to reduce trade costs, trade growth is likely to decline further over the remainder of the 2020s, according to the authors.

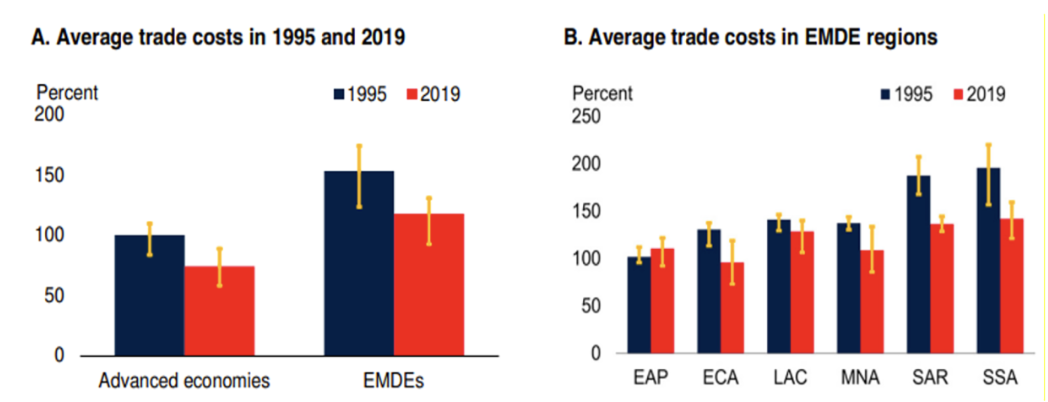

For all the global rhetoric about goods trade across borders, trade costs for goods are painstakingly high. On average, they are “almost equivalent to a 100% tariff, so that they roughly double the costs of internationally traded goods relative to domestic goods”.

As shown above, trade costs for agricultural products are (and have been) the highest in sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, the rhetoric around the potential of agriculture to lift people out of poverty and transform African economies is endless.

Africa remains a net importer of food, although it has 874 million hectares of arable farmland and almost 60% of the world’s uncultivated land. In the book “Making Africa Work”, this picture is quite bleakly demonstrated: only 43% of Africa’s arable land is in use, fertilizer use per hectare is just 13% of the global average, and Africa’s farmers have an estimated one tractor per 868 hectares.

Moreover, as its population has doubled overall and tripled in urban areas in the past 30 years, agricultural production and food security have struggled to keep pace.

As demonstrated by the remarkable progress of lifting 237 million people out of poverty through agricultural means in China, best practices have been established. This feat was achieved primarily due to effective state extension services and the successful utilization of local markets. The Chinese experience is an important example of how innovative policies and programmes can effectively combat poverty and uplift communities.

Trade tariffs, on average, only represent a small fraction – one-twentieth – of the average trade costs. Instead, transport and logistics, non-tariff barriers, and policy-related standards and regulations consume the majority of trade costs.

As highlighted in a recent publication, “The low road to economic ruin, as illustrated by a trip through Mozambique”, the cost of moving a 40-foot container from Beira to Lilongwe can amount to $4,750, which includes port and handling charges of $2,000 – almost 10 times the cost through Antwerp. Moving a container through Beira and on to Harare is $3,800, Beira-Lusaka is $5,300, and Beira to the Congo costs a whopping $9,000.

In comparison, shipping the same container 10,000km from Shanghai to Beira costs just $6,000.

These figures underscore the importance of competitiveness in today’s global economy and highlight trade costs’ significant role. We can significantly promote economic growth and development by addressing trade costs.

Competitiveness is crucial to success today, and trade costs are an “easy” fix for most.

Lessening these inflated trade costs in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), which largely include African countries, will involve “comprehensive reform packages that streamline trade processes and customs clearance requirements; enhance domestic trade-supporting infrastructure; increase competition in domestic logistics, and in retail and wholesale trade; lower tariffs; lower the costs of compliance with standards and regulations; and reduce corruption,” as the report clearly outlines.

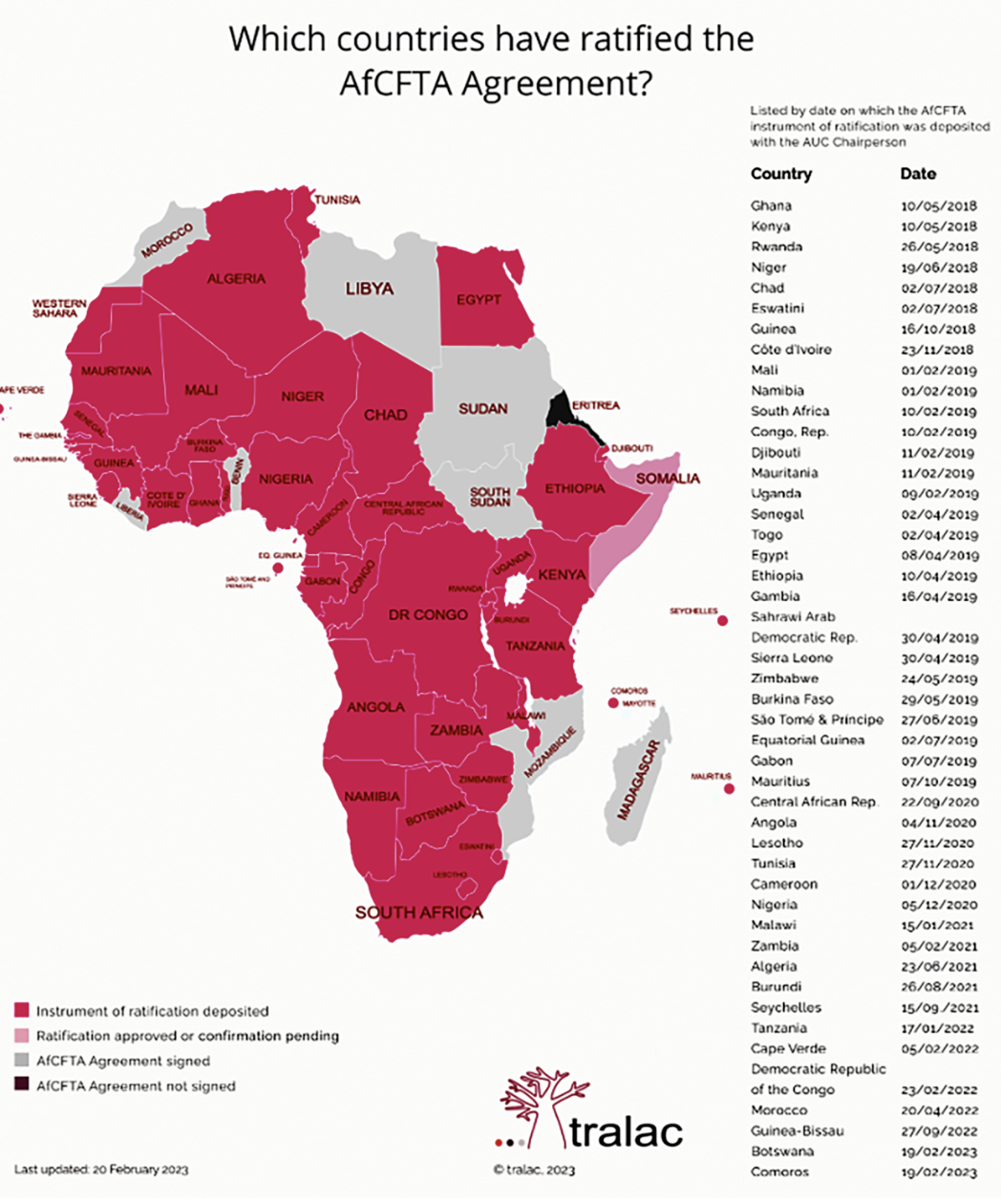

A fascinating finding was the impact of trade agreements on trade costs. Between 1990 and the early 2020s, the report found that declining tariffs were partly because of regional and multilateral trade agreements. This is affirming, especially in light of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which came into effect in January 2021 and aimed to create a single market for goods and services among African countries, to increase intra-African trade and boost economic growth.

Despite this optimism around the AfCFTA, which is warranted, there are reasons to be cautious. One of which is that the gains under AfCFTA rely in large part on collaboration between countries.

What happens if some of them, as we are seeing now, refuse to ratify all or some of the outstanding Protocols or delay ratification? What do we do then, as all the state parties must be bound by the AfCFTA agreement as a whole, and how, of all questions, does that impact potential gains standing on the other side of a full green light?

Therefore, African governments should continue deepening structural reforms that help reduce impediments to cross-border trade between borders, at the border and behind the border, including improved regional infrastructure, transit delays, customs compliance requirements, and transport-related trade costs. It is imperative that the underlying reasoning behind reforms and public policies in this regard have trade facilitation as an objective, thus simplification, harmonization, modernisation and efficiency.

Evidence from the continent suggests a more comprehensive approach to addressing elevated trade costs. According to the report, the Great Lakes region in Africa is an example of a successful trade reform programme where “improved trade and commercial infrastructure in the border areas and simplified border crossing procedures have been credited with improving accountability of officials, reducing rates of harassment at key borders (from 78% to 45% of survey respondents in south Lake Kivu), extending border opening hours, increasing trade flows, and doubling border crossings.”

Again, simplification, harmonization, modernisation and efficiency.

Final thoughts

In their concluding remarks, Ohnsorge and Quaglietti reinforce the importance of this assessment: “Despite a decline over the past three decades, international trade costs are high. In EMDEs, they amount to the equivalent of a tariff of more than 100%: thus, they roughly double the price of an internationally traded good relative to a similar domestically traded good. Trade costs are on average about four-fifths higher for agricultural products than for manufactured goods and more than one-half higher for EMDEs than for advanced economies.”

Given the tremendous economic potential of reducing trade costs for Africa, its governments and leaders must confront these issues with seriousness and urgency.

While countries could significantly cut their trade costs by adopting the technical recommendations around trade facilitation, the grunt of the work will also lie in commitment from political heads to have the tough conversations and negotiations and be willing and dedicated to implementing them. And doing them better than others.

Finding the right balance between national and regional priorities too will be of critical importance. It is not easy work, but it is the right kind of work. It is what is required to yield some semblance of real growth and economic development.

This article originally appeared on the Daily Maverick

Photo: iStock