News

Ramaphosa Kicks Can Down the Road with ‘Government of National Unity’ Play

President Cyril Ramaphosa has for the moment dodged choosing a coalition partner by proposing a ‘government of national unity’ which conceivably could include parties that have diametrically opposed views on all major policy issues.

Research Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

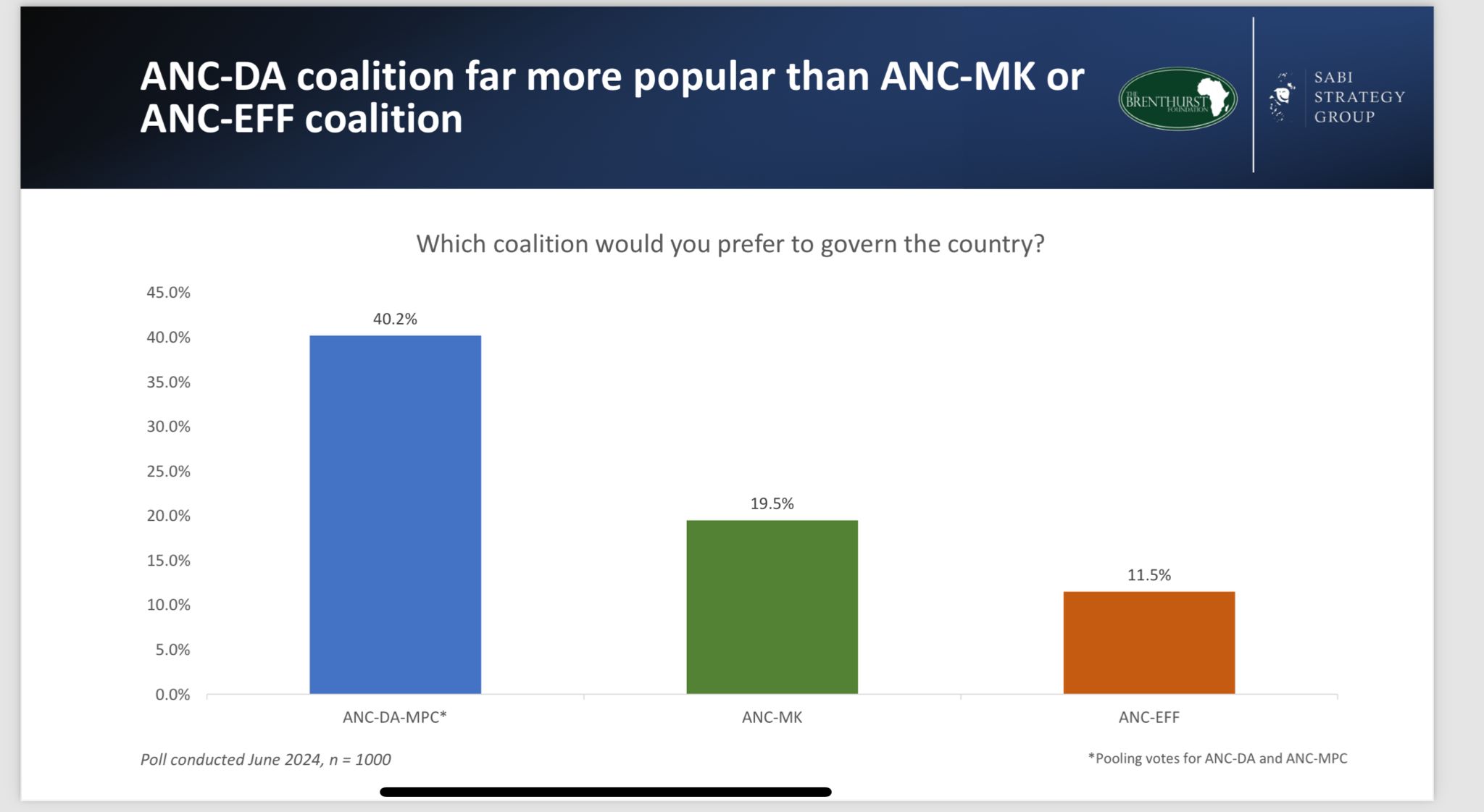

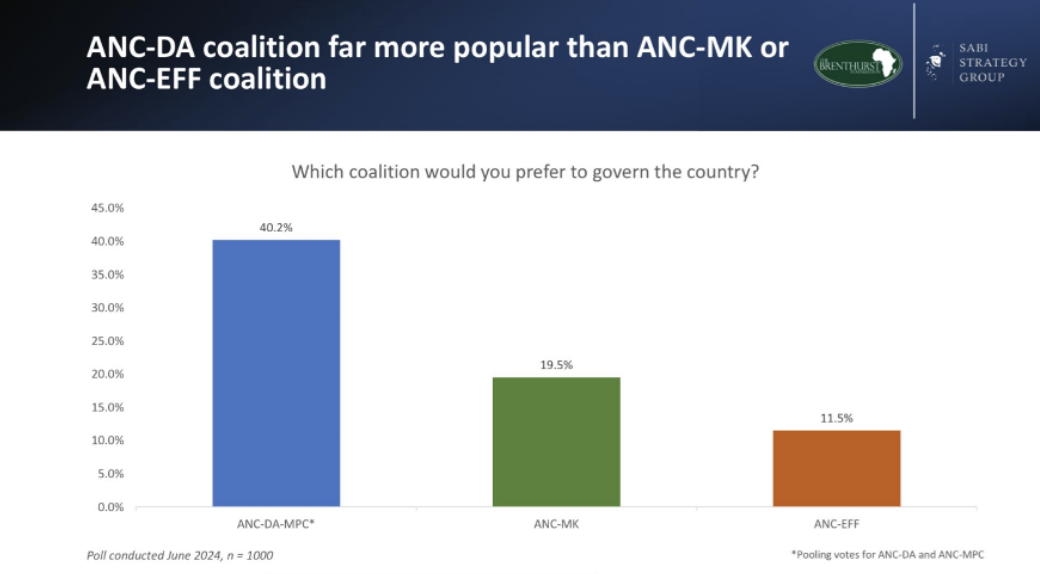

South Africans are clear on the coalition they would prefer to rule the country, the first opinion poll on the matter since last week’s election shows.

More than 40% surveyed said they would back an ANC-DA coalition, possibly including other members of the Multi-Party Charter such as the IFP and FF+.

Only 19.5% supported an ANC-MK Party coalition, while far fewer — 9.5% — supported an ANC-EFF coalition. Just under 6% favoured an ANC minority government.

The poll conducted within a week of the 29 May election which saw ANC support fall to 40.2% was based on telephonic interviews with a sample of 1,000 South Africans, using the same methodology of The Brenthurst Foundation’s pre-election polls which have proven accurate.

But President Cyril Ramaphosa has for the moment dodged choosing a coalition partner by proposing a “government of national unity” (GNU) which conceivably could include parties that have diametrically opposed views on all major policy issues.

Ramaphosa said he was making the proposal because, “We are at a moment of fundamental consequence. We must act with speed to safeguard national unity, peace, stability, inclusive economic growth, non-racialism and non-sexism. We will invite political parties to form a government of national unity.”

He mentioned “constructive discussions” with the EFF, IFP, DA, NFP and PA.

What he did not mention is that some of these parties hold radically different views on the Constitution, the rule of law and sound fiscal management.

The reality is that, despite the President’s predilection to kick the can down the road, the ANC faces a stark choice: Reinforce the pro-Constitution centre that wants to see sound economic management and inclusive growth or pivot to the populist left that wants the constitutional order upended and the introduction of radical economic policies.

For the country, the choice — and the outcome — is fundamental. It will determine South Africa’s trajectory for years to come, affecting the strength of independent institutions and thereby the rule of law and investment.

But there is one small problem: It requires Ramaphosa to make a serious and defining choice, something which he has avoided doing so far, with disastrous effect, during his presidency. As he selects membership of a GNU, now is his moment to place himself on the right side of history, on that which aligns with the document — the Constitution — for which he was partly responsible.

This moment is not about appointing committees, task teams or working groups, it is not even about “consulting broadly” within the party where all manner of interests, including the preservation of 30 years of rents, are simmering.

It is first and foremost a moment that requires leadership: Looking up to the horizon, beyond the party bubble and placing the country’s interests ahead of the party’s. This is the view that some other parties have already taken.

The DA, which could happily sit on the sidelines and amass political capital as a GNU coalition stumbles from one corruption scandal to the next, and from one governance mishap to another, has said it is ready to enter an arrangement that would protect the country against populism.

Julius Malema’s EFF is willing to enter a coalition, albeit for very different reasons. It wants to advance a populist redistributive agenda which will no doubt offer plenty of opportunities for its Champagne-loving leaders to improve their bank balances.

The costs of dithering

The danger is that Ramaphosa’s denial of the existence of this hard choice and dithering over this direction will carry its own costs, promising five more years of muddling along towards low growth and continued state decline.

There are many ways for the ANC to continue to prevaricate on its governance choices, even with the GNU announcement. The first is to attempt to include the EFF (and perhaps the MK party if it ever answers the phone) on one side of a GNU and the DA on the other, placing Ramaphosa handily in the middle, where he is most comfortable.

Such an option would only work if the EFF was willing to commit to setting aside its anti-constitutional policies and to working constructively and pragmatically towards clean, efficient and effective government, something it is yet to demonstrate in practice where it has been in coalitions. Without such a condition, it is unlikely to expect the DA and the IFP to join a GNU. Moreover, the problem is whether, even if it does promise to renounce its manifesto shibboleths, the EFF can be taken at face value, or if its cheque will be forever in the mail.

While many Pollyannas are summoning from the dead the spirit of 1994, this GNU won’t have the horns to turn the ship of state around. Instead, it will lead to an unstable government where departments will go their separate way on policy. Some will be profligate spenders perpetually caught in scandal, others will continue the tradition of genteel decline and yet others will struggle to get things moving as the civil service malaise morphs into an endless episode of Yes, Minister, but absent the humour. Rather, the overall effect will be poor economic outcomes and a further loss of confidence in democracy.

If the GNU was not to work, another dithering strategy would be for Ramaphosa to seek the position of President without a coalition agreement in place. This will take place after several humiliating rounds of voting, and includes the tantalising possibility of all the opposition parties present (MK promises not to attend) ganging up and choosing a different President just to make a point.

Another dithering strategy would be a so-called confidence and supply arrangement, essentially where a coalition is formed around parliamentary support for the executive, where parties (or independent members) agree to support the government in critical votes including motions of confidence and budget votes.

This arrangement risks institutionalising dysfunction if legislation presented by the ANC centre cannot be agreed by the legislature, or empowering the populists as Parliament becomes the site of an unequal struggle between the executive and the legislature.

A decision taken to move forward decisively with a new, efficient, corruption-free administration where technocratic skills and delivery are prized over all else requires leadership and choosing an alignment most likely to deliver that outcome.

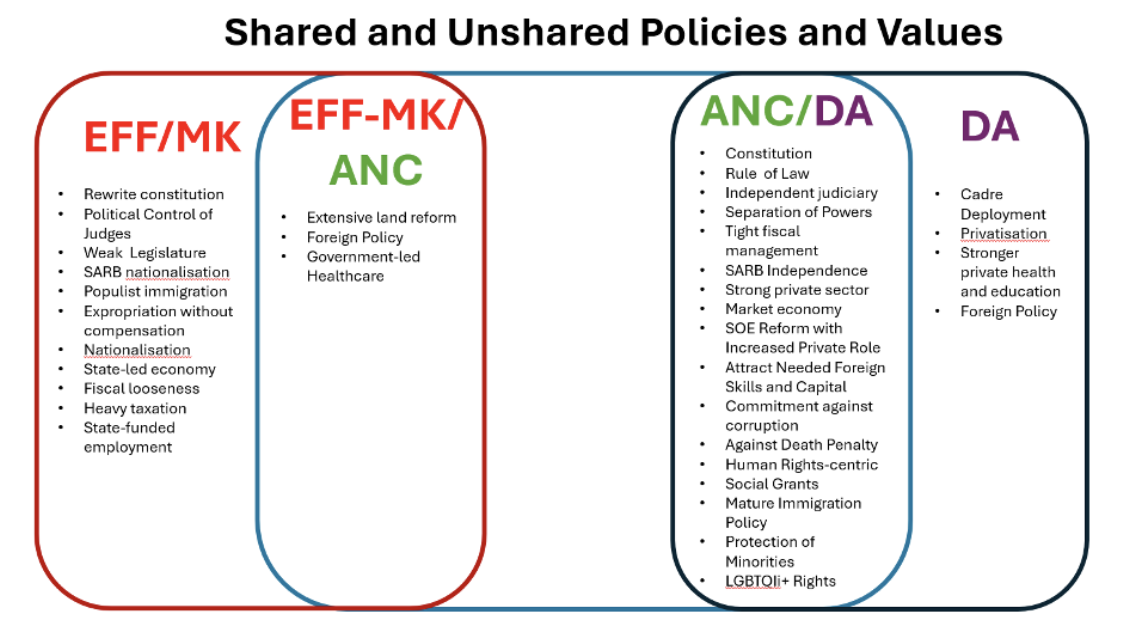

Rather than avoid the hard choice or gaze at the navels of their social media followers in search of fuzzy advice, the ANC would do well to sit down with the manifestos of the parties and draw up lists of what is actually shared — or not shared — by potential partners in the mooted GNU.

One such list doing the rounds looks like this:

It is not hard to see where the majority of voters reside in this diagram, one borne out by the results of the recent coalition preference survey.

‘Counter-revolution’

There are febrile voices in the public space crying “counter-revolution” at the idea of the ANC, IFP and DA getting together to form a 66% coalition of the centre, with or without a GNU, but they represent a minority within the minority that is the ANC. The response is, of course, if revolution means 30 years of corruption, unemployment, social disintegration, miseducation and ill health, then maybe the other option should be tested.

Moreover, it is the ANC itself which has rejected the practicality of working with the EFF. The ruling party’s 2023 report noted that it should review its “damaging” coalitions with the EFF. In an agreement whereby smaller parties’ councillors are made mayors, the ANC and EFF have governed together in three metros — Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni and Nelson Mandela Bay.

In a report to the National Executive Committee, David Makhura, the ANC’s head of political training, made it clear that he believes coalitions with the EFF should be reviewed because they are “more damaging than helpful”.

The former Gauteng premier said that the ANC’s research showed that the EFF continued to grow in by-elections by largely targeting the “traditional [voter] base” of the ANC and that the EFF “supports the Constitution and the law when decisions favour it. It has fashioned itself as an anti-establishment party. But, in reality, it is proto-fascist party run dictatorially.”

There is a chance that South Africa is at a moment of renewal, of a coalition of constitutionalists that puts governance and people at the heart of its politics. This would be a profound and inspiring choice, but one that can only become more difficult as the dithering drags on.

This article originally appeared on the Daily Maverick.