News

Op-Ed: Now or never for the international community in Zambia

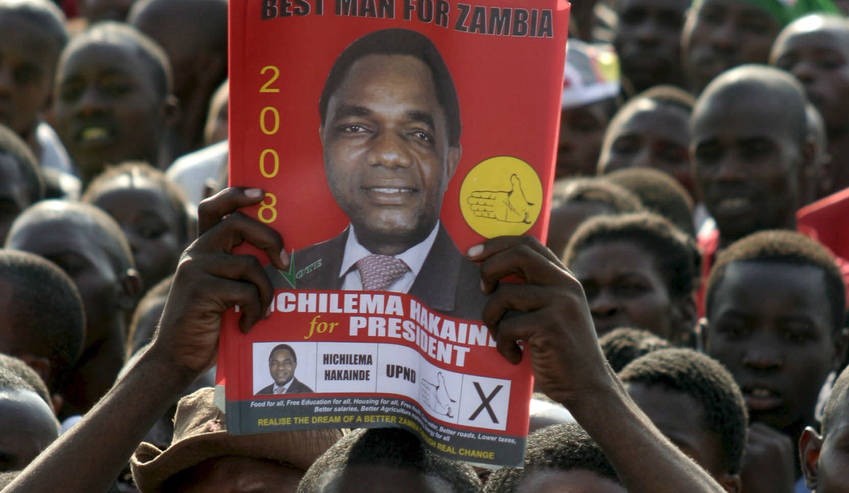

The arrest and incarceration of a Zambian opposition leader could be a feint to test the response of the international community. If it's limp, expect a wider and possibly even more violent crackdown.

Hakainde Hichilema, the leader of the Zambian opposition United Party for National Development (UPND), was arrested by police in his Lusaka home on Tuesday, 11 April.

It was a well organised night attack. Armed police and paramilitaries in plainclothes switched off the power to the house and blocked off access to the main roads before breaking down the entrance gates to the property.

Once inside the police liberally fired tear gas and, according to HH, as he is widely known, “tortured” his staff and ransacked the New Kasama property. In an affidavit of events, this involved stealing “colossal” amounts of cash, along with carpets, food and apparently just about anything else the invaders could get their hands on.

The businessman-turned-politician barricaded himself and his family in a safe-room in the house, sending out a torrent of urgent texts just after midnight highlighting his plight to friends and the media, before surrendering to police mid-morning once his lawyers had been permitted access.

Hichilema has now been charged with treason, and is being held at Lilayi Police Staff College outside the capital for questioning.

Since those accused with treason do not receive bail, he could be in for a long time. Access to the restricted Lilayi compound has so far been denied to his lawyers.

Equally, this event has been a long time coming. Most recently, Hichilema’s motorcade apparently failed to give way to that of President Edgar Lungu in Mongu three days earlier, spiking tensions. But relationships have been fraught since the national election in August 2016. Although Lungu was declared the official winner, the UPND claimed massive fraud before, during and after the voting – from the closing down of the main opposition newspaper to the failure to publish results at ballot stations and, most ominously, the slowing of the counting process, always a sign that the rig is in.

HH and his supporters have since as a result refused to acknowledge Lungu as president.

This may explain some of the venom in the raid. According to the opposition, the heavily armed police officers defecated in the house and peed on Hichilema’s bed, “trashing” the family home. The tear gas, which could reportedly be smelt from a long way away, caused harm to his wife and children, who are known to be asthmatic.

But there are deeper reasons behind the violence. The irregularities in the election were brushed over by an international community for whom the criteria of a free election are not the adherence to those democratic norms and standards they would like to see in their own countries.

This is not just a Zambian problem of course.

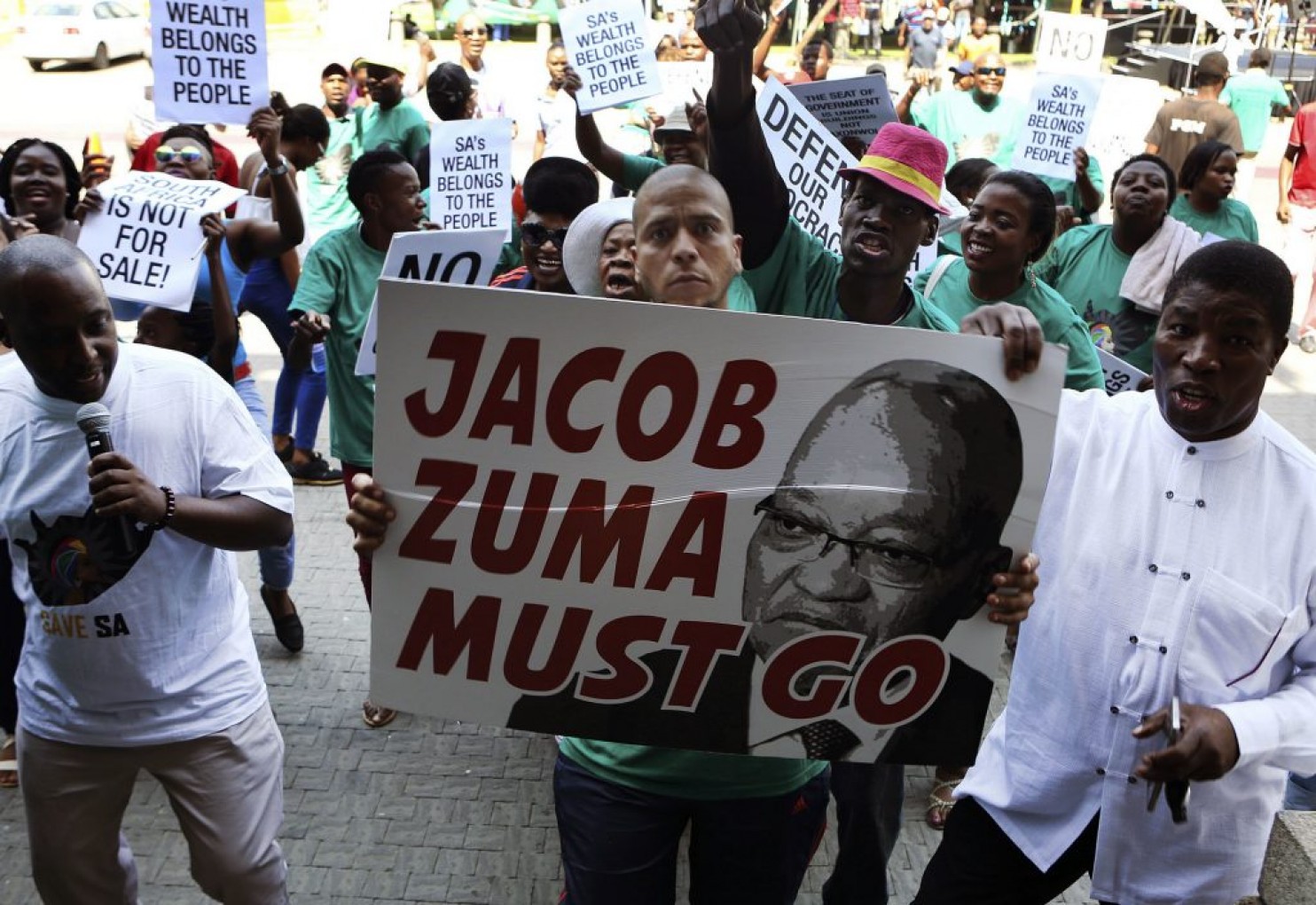

The regional environment, and especially the emergence of a patronage regime in the hegemon, South Africa, may also have encouraged Lungu and his Patriotic Front to follow a similar path. This includes ramping up pressure on foreign investors, involving cutting back on expat numbers and enforced local buying from PF cadres.

No doubt the international community would prefer to see Zambia’s political implosion as the result of both sides seeking conflict. That’s a cop-out. The violence is a result of a failure to ensure that decent standards were maintained in the election. Such a “shared responsibility” analysis fundamentally fails to acknowledge, too, the state’s virtual monopoly on the levers of violence.

To charge Hichilema for treason for interfering with a motorcade would seem to be self-defeating. Yet it could also be a feint to test the response of the international community. If it’s limp, expect a wider and possibly even more violent crackdown.

The target on 11 April was not just HH, but democracy in Zambia and by implication, the region. Resisting that requires international action and voice. The alternative is much worse, given the clear link between democracy and development, despite the oxymoronic notion of a “benign African dictator”. If the international community cares about this, and human rights and freedom of speech, it should apply pressure on Lungu to release HH immediately.

If it fails to do so, perhaps it is time for a frank conversation on whether diplomacy in Africa is fit for purpose.

This article was originally published in The Daily Maverick.