News

Nobel Laureate: Democracy and Freedom are in Crisis

The erosion of democracy is intertwined with a crisis of freedom. The most common path toward democratic decline is via the election of authoritarian leaders who then clamp down on media, dissent, and opposition forces, says Nobel Laureate, Daron Acemoglu, in this speech to the Atlantic Council

This is the text of a speech delivered by Nobel Laureate, Daron Acemoglu, at the launch of the Atlantic Council's Freedom and Prosperity Index in Washington

Democracy and freedom are in crisis. Freedom House reports that democracy around the world has been in constant retreat for seventeen consecutive years.1 In 2021, sixty countries experienced declines in their democracy score, while only twenty-five showed improvement. Today, the world is less democratic than it has been at any time since 1997. Concurrently, there has been a steep decline in support for democracy. In international surveys, 60 percent of respondents reported a positive view of democracy in the mid-1990s; the number now stands at 50 percent.2

The erosion of democracy is intertwined with a crisis of freedom. The most common path toward democratic decline is via the election of authoritarian leaders who then clamp down on media, dissent, and opposition forces.3 Censorship is on the rise and freedom of expression is in decline around the world, led by China, where government surveillance has intensified, aided by controls over media, social media, the Internet, and all kinds of nongovernmental organizations, including businesses.4 Similar trends are visible not only in countries like Iran and Russia, similarly recognized for their repressive regimes, but also in the Middle East, Hungary, Turkey, India, Pakistan, Mexico, and several countries in Africa. There is growing demand for Chinese technologies for surveillance, exports of which are growing around the world.5

The chapters in this handbook summarize these worrying developments in rich detail. While many of them also point in hopeful directions, there are reasons to worry that even worse times may be ahead for freedom and democracy. Wars in Ukraine and the Middle East have already intensified controls over free expression.6 The COVID-19 pandemic provided an excuse for many governments to further tighten the screws, and in several cases these controls have remained in place even after the pandemic subsided.7 All of this could be made worse if, as forecasted, refugee and immigrant flows increase rapidly as a result of global climate change and domestic politics in destination countries shifts further in a nativist-populist direction.

Even more worrying are two major economic and technological developments which will likely continue to push toward more intense authoritarianism. The first is the growing sense that millions (or even billions) of people are being left behind while a global elite are benefiting from economic growth and technological progress.8 This grievance has been central to the rise of left-wing and right-wing populist regimes in both established and nascent democracies, and this worrisome trend shows no sign of subsiding.9 The second is the rapid pace of advances in artificial intelligence (AI), which has been used for data collection on a massive scale by many governments and multinational corporations, and which has also enabled large-scale surveillance, as in China, Russia, and Iran. Although AI technology could be developed in less repressive ways, its current trajectory is concerning for democracy and liberty.

A simple framework

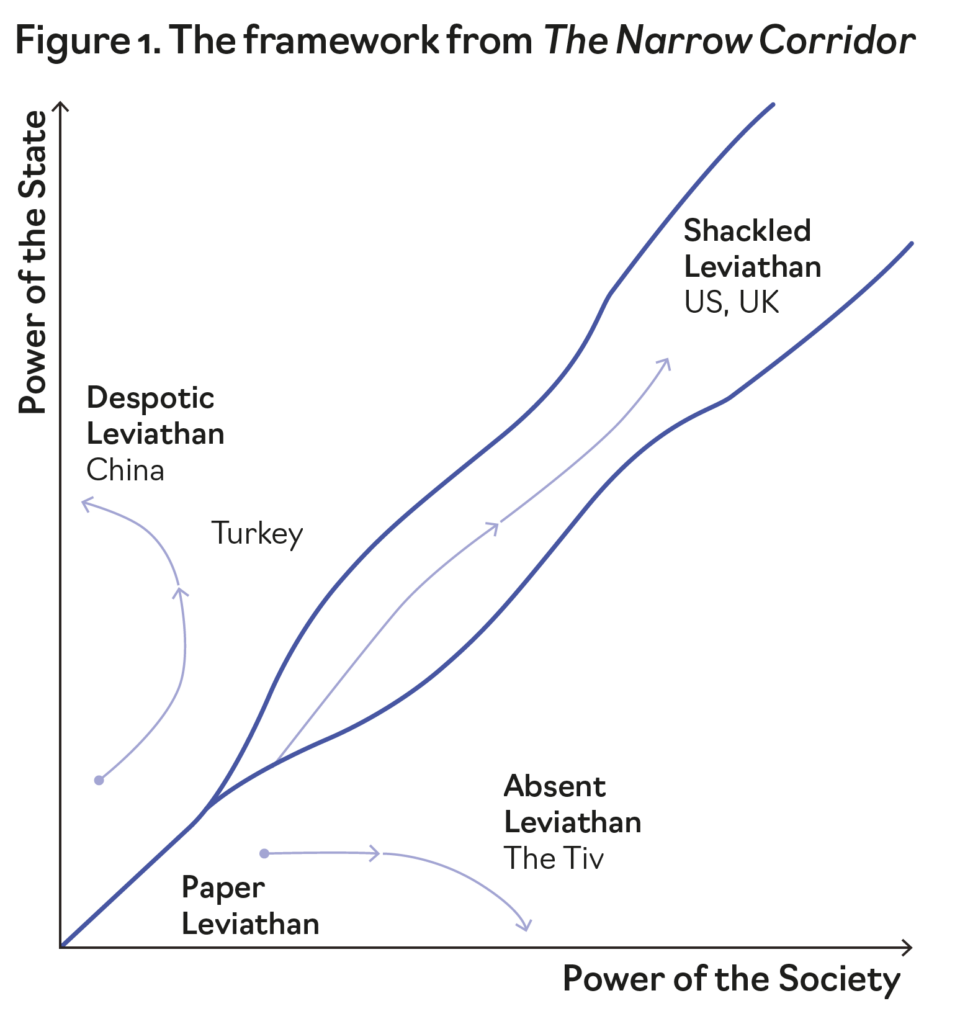

There is still much we do not know about the consequences for prosperity, inequality, and the future of democracy and freedom. I argue in the rest of this foreword that a simple framework—building on my 2019 book The Narrow Corridor, jointly written with James Robinson—may be useful to shed light on the problems of democracy and freedom, and point to pathways for developing institutions, norms, and practices for democratic rejuvenation.10

The main thesis of this framework can be summarized by Figure 1 below, which I borrow from the book.

In our framework, state-society relations determine the nature of political power. This is summarized by the three regions depicted in the figure. The region on the left is the “basin of attraction” of the “Despotic Leviathan,” which signifies a state that is despotic in the sense that it can implement policies or impose its wishes without input from society. The implied dynamics, reminiscent of a simplified version of Chinese political history, are inexorably toward lower levels of societal power. This is the reason why the trajectory indicated there moves gradually toward the vertical axis, where society’s power against the state reaches a minimum.

The polar opposite of the despotic path is one where the state and its institutions are weak and society’s traditions and organizational capacity are strong. At first, this might appear as a remedy against state repression. In reality, it is also inimical to freedom. It impedes the development of political hierarchy, a precondition for the emergence and evolution of state institutions, including a legal system and regulatory rules that are essential for protecting individuals against predation, expropriation, and intimidation. Even when states do appear within this context, they are weak and, in fact, often absent from large parts of the territory they are supposed to control. James Robinson and I thus labeled them as “Absent Leviathans.” These dynamics lead toward even greater state weakness.

More interesting is the region in the middle: “the narrow corridor.” This corridor is defined by a balance of power between state and society. The trajectories in this region look very different than those outside of it. This, we argue, is the hallmark of a different type of state and different nature of political power. We label it the “Shackled Leviathan” to capture the notion that the state is still strong, but it is monitored, challenged, and controlled by society—and, ultimately, by democratic institutions.

The heart of our theory is that true democratic participation and liberty, as well as economic incentives encouraging innovation and experimentation, can only flourish within the corridor. The corridor itself, though precarious at the best of times, can be bolstered by societal mobilization and participation. Institutions matter, but neither a cleverly designed constitution nor the correct set of institutional guardrails are sufficient by themselves to protect the corridor, nor are they a true bulwark against threats to democracy. Put simply: democracy is seldom given to the people, and it is often taken; thus, democracy is almost always in need of defense by the people.

There is another important aspect to the corridor, emphasized by the direction of trajectories within it, contrasted with those outside. Outside of the corridor, historical dynamics are likely to weaken one party as they strengthen the other. Inside of the corridor, however, the capacities of both state and society can rise in tandem. There are two synergistic reasons for the mutually beneficial dynamics within the corridor. First, state and society are locked in a fairly balanced competition. As state institutions become stronger—for example, because of new exigencies—society strives to increase its own capacity in order to control the emboldened state. Second, when balanced in terms of their capacities, state and society can cooperate. For example, when institutions and societal mobilization mean that an upstart politician cannot immediately hijack the public budget or misuse information that state agencies collect, people will be more willing to allow greater taxation and information collection. The centerpiece of this state-society cooperation is a degree of trust between state institutions and the population at large.

Both the positive-sum state-society competition and the trust in institutions are fragile, however. Competition can easily spin out of control, and trust is easier to destroy than to build.

This framework also highlights why societal norms are so important. These norms determine the boundaries of what elites and the agents of the state are expected to do, and how much trust they can command. These norms also shape how society mobilizes and resolves its own differences in the service of organizing against elites and impositions from the state.

Norms themselves are shaped by broader cultural trends, and while The Narrow Corridor did not study cultural dynamics in detail, our more recent work has proposed a complementary framework for doing so.11 This framework starts from the observation that no human society possesses an unambiguous and unchanging cultural structure. Rather, different human communities have a reservoir of “attributes,” which gel together in distinct ways to create different underpinnings of political and social behaviors. The importance of this perspective is that we should not think of culture as a hard constraint on democracy or freedom, but rather as the language through which ideas related to democracy, liberty, and inequality can be articulated. Nevertheless, there is persistence in culture. Once freedoms start to be sidelined, it becomes more difficult to build the cultural tools to defend them. Once trust between state and society is destroyed, it also becomes harder to generate the ideas and coalitions needed to rebuild it.

In The Narrow Corridor, James Robinson and I trace the history of many historical polities via these trajectories and explain what sorts of events can place a society inside or outside the corridor and what shapes its boundaries. Most importantly, the historical account reveals how the process of entering and traveling within the corridor is a slow, conflict-ridden process, and how trust between state and society develops gradually and often painfully over time—but also how this trust can be easily destroyed, and how competition can quickly turn zero-sum.

The eclipse of democracy and freedom

What does this framework imply for the current difficulties and future prospects of democracy and freedom? Two complementary processes can be identified. First, societies inside of the corridor have experienced weakening democracies and intensifying clampdowns on freedoms. Second, Despotic Leviathans outside of the corridor have become more adept at defending their nondemocratic regimes against the counterbalancing powers of society, thanks to China’s rise, the use of AI and related technologies, and also because democracies themselves have become weaker. I now focus on the first process, returning to the second process later in this foreword.

The fact that support for democracy among the people has declined—rather than authoritarian leaders merely clamping down on democratic rights and freedoms against the people’s wishes—provides an important clue about the problems of democracy and freedom. The causes of this deteriorating support for democracy are explored in my joint work with Nicolás Ajzenman, Cevat Aksoy, Martin Fiszbein, and Carlos Molina.12 We find that people who have experience with democratic institutions tend to support them. Hence, a history of democracy should boost people’s willingness to defend the regime. But a more detailed look at the data reveals that the relationship between democratic experience and support for democracy is far from unconditional. It is only people who have experience with successful democracies—meaning democracies that deliver the kinds of economic performance, public services, and outcomes that they desire—that support democracy. In fact, we found that people who live under unsuccessful democracies do not increase their support for these institutions at all.

So, what is it that people want from democracies? Our results suggest several important dimensions of success: economic growth (democracies that get mired in economic crises do not garner support); peace and political stability (wars or instability are of course not what people want); control of corruption; good public services; and low inequality. These last three are particularly important, because they underpin one of the important pillars of trust between state and society, as emphasized by the framework in Figure 1. The cooperative, positive-sum relationship between state and society collapses when trust in democratic institutions is eroded. This becomes much more likely when democratic institutions malfunction, and especially when they enable malfeasance by public officials, fail to deliver basic public services, and cannot (or choose not to) control inequality.

I believe it is these dimensions in which democracies, and more generally societies, in or near the corridor, have failed in recent decades. There are several reasons for this failure. Some of them are technological, some of them economic, and some of them political. New technologies have favored the very well-educated elite both in industrialized and developing nations, and governments have not taken steps to redress these inequities. Economically, the rapid drive toward globalization, transmogrified by the rapid accession of China into the global trading order, has contributed to the same trends.

But even worse for democracy’s reputation has been the policy response to these trends. Neither technology nor globalization are acts of nature. They are choices that societies make about how to use existing scientific know-how, what types of new technologies to develop, and what kind of globalization to implement. In the case of industrialized nations, led by the United States, these were choices made by political and economic elites. Trust among the people was markedly undermined—especially for people who were not among the winners from these processes—because these decisions were made by an insular technocratic elite who kept claiming (with very vocal support from the mainstream media) that everybody would benefit from unlimited technological growth and expansive globalization. In the United States, nothing of the sort happened. For example, low-education households have seen their real incomes collapse since 1980. In several other industrialized nations, the trends are less clear-cut, but people in the bottom half of the income distribution did not receive much of the promised benefits. At the same time, the technocratic elite became more and more integrated with the business elite, convincing many that corruption was on the rise (whether this was true or not).

This collapse of trust in public institutions and public servants is inimical to life in the corridor, and it has been a major driver of eroding support for democracy. It has also been an important force toward declining respect for democratic rights and broader freedoms.

As democracy’s reputation has become tarnished in the West, this has created an opening for authoritarian regimes, led by China and Russia, to solidify control over their populations, with disastrous effects for freedom around the world.

If this account is correct, it is the failure of democratic institutions that is threatening the balance within the corridor. The corresponding declines in trust and support for democracy make the implications for future political regimes and myriad freedoms and rights especially dire.

Will it get worse?

There are at least three reasons to worry that the trends we are seeing could get worse.

First, there is no obvious end to the slide of democratic norms around the world. As democracies continue to perform poorly on many dimensions that their citizens care about and as powerful autocracies, such as China and Russia, expand their global reach and propaganda, it would be quixotic to hope for an immediate turnaround. Historical evidence is consistent with the idea that, once waves of democracy start, they go on for a while.13 Likewise, once the decline of democracy is underway, we may see further slides for quite some time.

Second, the key forces that have led to the benefits of prosperity not being shared equally are still present. As Simon Johnson and I argue in Power and Progress,14 the main factor leading to growing inequality and lack of wage growth around the world has been the use of digital technologies to drive workplace automation and worker disempowerment. With recent advances in generative AI, these forces may have gone into overdrive. While there is nothing inherent in the nature of AI that should make it always eliminate labor and increase inequality, our current technological trajectory is toward automation and a reduced role of labor across diverse sectors of the economy.15 If this technological trend continues, it will exacerbate the failure of democracies to create shared prosperity. Although certain aspects of globalization may have slowed down, the role of multinational corporations and other dimensions of global integration are likely to increase, which could create another set of forces toward unshared prosperity.16

Third, AI also has direct impacts on democracy, which will likely exacerbate democratic tensions in the years to come. As mentioned above, this is both because AI is being used increasingly skillfully by autocratic regimes to quell discontent and demand for democratic rights,17 but even more fundamentally, it is because AI is distorting political communication and discourse in electoral democracies around the world.18 The role of Facebook and other social media platforms in fostering filter bubbles and polarization and fomenting partisanship and misinformation during the 2010s is now well understood. There are concerns that, with advances in generative AI, even worse practices will take root in the new social media ecosystem.19

While several political, economic, and technological trends may augur hard times for democracy and freedom, there is one small silver lining suggested by the framework in The Narrow Corridor: leaving the corridor is not permanent, and countries that have recently lost the balance between state and society will also be the ones where this balance is still partly present. As conditions change, and as pro-democracy forces and measures strengthen the demand for democratic and civil rights, it is possible to reenter the corridor. For example, after the murderous, totalitarian Nazi regime in Germany, the country was able to rebuild a balance between state and society and develop fairly healthy democratic institutions in the postwar era.20 The same perspective provides some hope that, even as we are witnessing the slide of democratic norms and institutions, rebuilding them is a possibility.

What to do?

Almost all of the chapters in this book suggest ideas to rejuvenate freedom. Let me add to these valuable insights by summarizing some perspectives from the framework presented here.

To put it simply, the best way to counter the current pernicious trends is to create another wave of democracy, similar to the one witnessed after the collapse of military dictatorships in Southern Europe in the 1970s. But how?

There is no surefire way of achieving something so ambitious. But I would like to briefly present a couple of ideas.

- Rebuild support for democracy. Democracy is nothing without people’s support. The first step in improving the future of democracy and freedom is to rebuild support for democracy within democratically governed populations, then hope that these ideas will spread around the world. In my assessment, the only way this can be achieved is by democracy performing better, at least starting in a number of key places, such as the United States, Western Europe and Latin America. Democracies in these ideological battlegrounds need to show that they deliver in terms of economic growth, shared prosperity, control of corruption, and responsiveness to people’s needs and wishes. The role of shared prosperity here cannot be overemphasized. Democracy will continue to lose support if it is seen as the handmaiden of a two-tiered society in which a small group of elites benefits from economic growth and technological change while the rest become increasingly dependent.

- Trust in institutions. Concurrently, democratic institutions need to foster people’s trust. This again starts with performance. But procedures matter too. One of the reasons why democracies started losing people’s trust and support is because of an error of “technocracy.” Increasingly, many segments of the population are becoming disillusioned with democracies because they think that, under the veneer of democracy, a small group of technocrats, in cahoots with economic and political elites, runs the show. This state of affairs is not conducive to trust in institutions or support for democracy. To get out of this situation is certainly not easy, especially after democratic norms have become weakened. Sidelining experts and expertise from policy making, or enabling the emergence of a tyranny of the majority that could damage civil rights and minority rights, would certainly be disastrous for broad freedoms. The solution then must be sought in democratizing procedures subject to well-articulated constraints. The alternative to technocracy should thus not be viewed as “mob rule,” but as institutions that are truly responsive to people’s needs and concerns. These institutions should be built and should function within well-defined and communicated constraints, set by constitutions, and a firm commitment to minority and human rights.

- The right kind of empowerment for civil society. The framework in The Narrow Corridor puts special emphasis on the role of civil society. The weakening of democratic norms and freedoms around the world has coincided with civil society becoming either weaker, as in many autocratic regimes, or more polarized, as in the United States and Western Europe.21 We need the right kind of empowerment for civil society, which means civil society becoming a true bulwark in the defense of freedoms and democracy. This must start with civil society organizations (CSOs) themselves recognizing that they should not be an instrument to suppress rights and freedoms. The tragedy in much of Western Europe and the United States today is that several CSOs have become active participants in banning free speech or silencing alternative voices.22 The right kind of civil society empowerment must start with a strong commitment to freedom of speech. All other concerns, including the fact that some groups may feel uncomfortable when certain ideas are expressed, must be subservient to this principle. It is only then that CSOs can be a true force against state repression and elite dominance and can help rebuild freedom and democracy.

Endnotes

1 Yana Gorokhovskaia, Adrian Shahbaz, and Amy Slipowitz. Marking 50 Years in the Struggle for Democracy. Freedom House: Freedom in the World 2023, March 2023, freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2023/marking- 50-years.

2 Daron Acemoglu, Nicolás Ajzenman, Cevat Giray Aksoy, Martin Fiszbein, and Carlos Molina, “(Successful) Democracies Breed Their Own Support.” Working paper, Review of Economic Studies, (2023, forthcoming). economics.mit.edu/ sites/default/files/2023-10/Successful%20Democracies%20 Breed%20Their%20Own%20Support.pdf; Daron Acemoglu, Nicolás Ajzenman, Cevat Giray Aksoy, Martin Fiszbein, and Carlos Molina, “Support for Democracy and the Future of Daron Acemoglu Daron Acemoglu is an Institute Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is also a fellow of NAS, APS, BAS, AAAS; the winner of BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Award, Nemmers Prize, Global Economy Prize, A.SK Prize, CME Prize, and John Bates Clark Medal; and the author of New York Times bestseller Why Nations Fail (with James Robinson); The Narrow Corridor (with James Robinson); and Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle over Technology and Prosperity (with Simon Johnson). Democratic Institutions,” VoxDev, December 19, 2023, voxdev. org/topic/institutions-political-economy/support-democracy- and-future-democratic-institutions.

3 Grzegorz Ekiert, Democracy and Authoritarianism in the 21st Century: A Sketch, Harvard Kennedy School, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Policy Briefs Series, December 2023, ash.harvard.edu/sites/hwpi.harvard.edu/files/ ash/files/democracy_and_authoritarianism_in_the_21st_century-_a_sketch.pdf; Larry M. Bartels, Ursula E. Daxecker, Susan D. Hyde, Staffan I. Lindberg, and Irfan Nooruddin, “The Forum: Global Challenges to Democracy? Perspectives on Democratic Backsliding,” International Studies Review, 25, no. 2 (June 2023); Robert R. Kaufman and Stephan Haggard, “Democratic Decline in the United States: What Can We Learn from Middle-Income Backsliding?” Perspectives on Politics, 17, no. 2 (2019), 417–32.

4 Sarah Cook, “Freedom of Expression in Asia: Key trends, factors driving decline, the role of China, and recommendations for US policy,” Freedom House, March 30, 2022, freedomhouse.org/ article/testimony-freedom-expression-asia; Gary King, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts, “How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, Not Engaged Argument,” American Political Science Review 111, no. 3 (2017), 484–501; Gary King, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts, “How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression,” American Political Science Review 107, no. 2 (May 2013), 326–43; Zhizheng Wang, “Systematic Government Access to Private-Sector Data in China,” International Data Privacy Law, 2, no. 4 (2012), 220–229.

5 Martin Beraja, Andrew Kao, David Y. Yang, and Noam Yuchtman, “AI-tocracy,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 138, no. 3 (2023) 1349–1402.

6 Anton Troianovski, Yuliya Parshina-Kottas, Oleg Matsnev, Alina Lobzina, Valerie Hopkins, and Aaron Krolik, “How the Russian Government Silences Wartime Dissent,” New York Times, December 29, 2023, nytimes.com/interactive/ 2023/12/29/world/europe/russia-ukraine-war-censorship.html; Dasha Litvinova, “The Cyber Gulag: How Russia tracks, censors and controls its citizens,” Associated Press News, May 23, 2023, apnews.com/article/russia-crackdown-surveillance-censorship-war-ukraine-internet-dab3663774feb666d6d0025bcd 082fba.

7 Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz, Democracy Under Lockdown: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Global Struggle for Freedom, Freedom House, October 2020, freedomhouse.org/report/ special-report/2020/democracy-under-lockdown; Richard Youngs, “COVID-19 and Democratic Resilience,” Global Policy, Policy Insights 14, no. 1 (2022), 149–56; Jacek Lewkowicz, Michał Woźniak, and Michał Wrzesiński, “COVID-19 and erosion of democracy,” Economic Modelling 106 (January 2022), 105682.

8 Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity (Hachette, PublicAffairs, 2023).

9 Sergei Guriev and Elias Papaioannou, “The Political Economy of Populism,” Journal of Economic Literature 60, no. 3 (2022), 753–832; Dani Rodrik, “Why Does Globalization Fuel Populism? Economics, Culture, and the Rise of Right-Wing Populism,” Annual Review of Economics 13 (2021), 133–70.

10 Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty (Penguin Random House, 2019).

11 Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, “Non-Modernization: Power-Culture Trajectories and the Dynamics of Political Institutions,” Annual Review of Political Science, 25 (2022), 323–39.

12 Acemoglu et al., “(Successful) Democracies Breed Their Own Support.”

13 Samuel P. Huntington, “Democracy’s Third Wave,” Journal of Democracy 2, no. 2 (1991), 12–34; John Markoff, Waves of Democracy: Social Movements and Political Change (SAGE Publications, Inc., 1996).

14 Acemoglu and Johnson, Power and Progress.

15 Acemoglu and Johnson, Power and Progress.

16 John G. Ruggie, “Multinationals as Global Institution: Power, Authority and Relative Autonomy,” Regulation and Governance 12, no. 3 (2017) 317–33; In Song Kim and Helen V. Milner, Multinational Corporations and their Influence Through Lobbying on Foreign Policy, Brookings Institution, December 2, 2019, web.mit.edu/insong/www/pdf/ MNClobby.pdf.

17 Martin Beraja, David Y. Yang, and Noam Yuchtman, “Dataintensive Innovation and the State: Evidence from AI Firms in China,” Review of Economic Studies 90, no. 4 (2023), 1701–23; Beraja et al., “AI-tocracy,” (2023).

18 Allie “The Repressive Power of Artificial Intelligence,” in Freedom on the Net 2023, eds. Adrian Shahbaz et al. (Freedom House, 2023) freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2023/repressive-power-artificial-intelligence; Daron Acemoglu, “Harms of AI,” The Oxford Handbook of AI Governance, eds. Justin Bullock, Yu-Che Chen, Johannes Himmelreich, Valerie Hudson, Anton Korinek, Matthew Young, and Baobao Zhang (Oxford University Press, 2024); Jessica Brandt, “Propaganda, Foreign Interference, and Generative AI,” testimony prepared for the US Senate Artificial Intelligence Insight Forum (Brookings Institution, November 8, 2023), brookings.edu/articles/ propaganda-foreign-interference-and-generative-ai.

19 Jonathan Haidt and Eric Schmidt, “AI Is About to Make Social Media (Much) More Toxic,” The Atlantic, May 5, 2023 theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/05/generative- ai-social-media-integration-dangers-disinformation- addiction/673940; Daron Acemoglu, Written testimony prepared for the US Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs hearing on “The Philosophy of AI: Learning from History, Shaping Our Future,” (November 8, 2023), hsgac.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/Testimony-Acemoglu-2023-11-08.pdf; Valerio Capraro et al., “The Impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Socioeconomic Inequalities and Policy Making,” SSRN Working Paper No. 4666103, December 15, 2023; Daron Acemoglu, Asuman Ozdaglar, and James Siderius, “A Model of Online Misinformation,” The Review of Economic Studies (2024, forthcoming).

20 Acemoglu and Robinson, The Narrow Corridor, Chapter 13.

21 Amber Hye-Yon Lee, “Social Trust in Polarized Times: How Perceptions of Political Polarization Affect Americans’ Trust in Each Other,” Political Behavior 44 (2022) 1533–54; Nicholas Charron, Victor Lapuente, and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, “Uncooperative Society, Uncooperative Politics or Both? Trust, Polarization, Populism and COVID-19 Deaths Across European Regions,” European Journal of Political Research 62, no. 3 (2022), 781–805; Shanto Iyengar, Yphtach Lelkes, Matthew Levendusky, Neil Malhotra, and Sean J. Westwood, “The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States.” Annual Review of Political Science 22 (2019), 129–46; Jennifer McCoy, Tahmina Rahman, and Murat Somer, “Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities,” American Behavioral Scientist 62, no. 1 (2018), 16–42.

22 Brenda Dvoskin, “Representation Without Elections: Civil Society Participation as a Remedy for the Democratic Deficits of Online Speech Governance.” Villanova Law Review 67, no. 3 (2022), 447–507; Robert Corn-Revere, “The Anti-Free Speech Movement,” Brooklyn Law Review 87, no. 1 (2021) 145–93; John Shattuck and Mathias Risse, Freedom of Speech and Media: Reimagining Rights & Responsibilities in the United States, Harvard Kennedy School, Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, 13 (2021), speech.pdf.

Daron Acemoglu is an Institute Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is also a fellow of NAS, APS, BAS, AAAS; the winner of BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Award, Nemmers Prize, Global Economy Prize, A.SK Prize, CME Prize, and John Bates Clark Medal; and the author of New York Times bestseller Why Nations Fail (with James Robinson); The Narrow Corridor (with James Robinson); and Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle over Technology and Prosperity (with Simon Johnson).