News

New US administration finds political foundation in creaky culture theory

Prominent in the 1990s and resurrected after 9/11, academics' predictions of a clash of civilisations has returned.

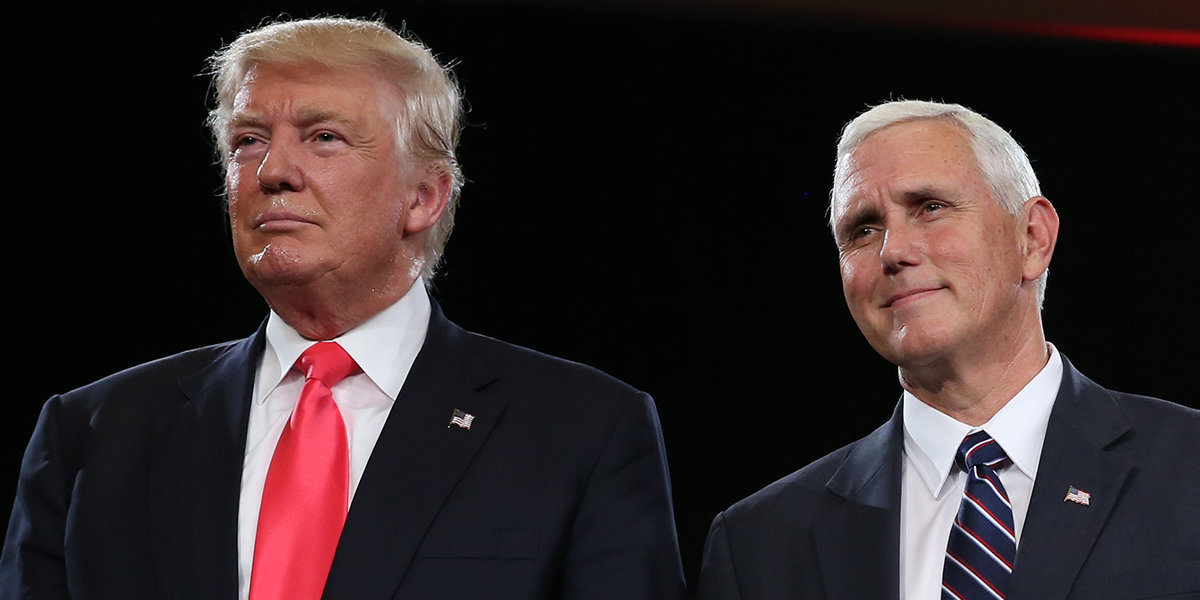

Twenty-five years have passed since Samuel Huntington first hypothesised a world torn asunder by clashing civilisations. After a lengthy sabbatical, the late Harvard political scientist is back in favour at the White House. President Donald Trump's closest advisers are big fans.

As with much else, Trump is at odds with considered opinion. Most experts want Huntington's paradigm buried in an academic graveyard. Breathe life into this baleful concept and it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy they warn.

Huntington set out his controversial thesis in a lecture to the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think-tank based in Washington, DC, in 1992. He argued that people's cultural identities would be the main source of conflict in the post-Cold War world. Wars would not be fought primarily for ideological or economic reasons. Instead, people would fight along the cultural cleavages that divide civilisations. Of the eight different blocs that comprised his civilisational map, he predicted the cleavage between the Islamic world and the West would be the bloodiest. "Islam's borders are bloody," Huntington averred, "and so are its innards."

His lecture became a sensational essay published the following year in Foreign Affairs and later a book. No concept of global politics attracted more scholarly attention in the 1990s. Yet intellectuals were generally unimpressed. Huntington's grand narrative was oddly bereft of actual "politics". He elided the complex jumble of different national interests and rivalries within each of his groupings. The dynamic interplay between civilisations was ignored. His empirical evidence was shoddy (mass bloodletting in the 20th century was mostly intracultural). From one of the finest scholars of his generation, it was disappointingly thin.

Singled out for particular scorn was Huntington's portrait of the Islamic world – of which he was plainly unfamiliar – as a monolith incurably opposed to western values. Then September 11 happened.

In the panic and fear sowed by al-Qaeda's co-ordinated attacks on New York and Washington in 2001, Huntington's book became a bestseller. Previously sceptical analysts came on board. Hawks in the still-young administration of President George W Bush seized on the idea that 9/11 was an extension of Muslim wars into the US, propelled by a renascent Islamic consciousness. The clash of civilisations was real, opined acclaimed author Robert Kaplan in the Atlantic Monthly, lauding Huntington for his prescience and for bravely "looking the world in the eye".

The fervour was short-lived. The White House's nation-building project in Iraq would affirm Bush's healing cry after 9/11 that "Islam is peace". And the notion that western-style democracy was inherently conflictual with Muslim societies would be dispelled.

But the internecine carnage unleashed by the US invasion proved no less contrary to Huntington's caricature of an unvariegated Islamic world. The rift between Sunni and Shia within Islam seemed more prone to violence than any putative fault line between Islam and the West. The US subsequently doubled down on existing ties with Muslim allies as the best defence against another 9/11.

It would be left to Bush's successor to hammer the final nail in the coffin of Huntington's theory. Barack Obama famously refused to use the term "radical Islamic terrorism" or any variations thereof. The former president steadfastly held that such language alienated Washington's Muslim partners in the fight against extremist groups such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. Their victims were, overwhelmingly, fellow Muslims. US deeds and words should not embroider depictions of the West as an enemy of Islam. That's precisely what Huntington did. But no more.

Bannon is the former head of far-right US news site Breitbart. He's also a catastrophist, convinced the US is in the beginning of an existential civilisational war. Everything is part of that conflict

Alas, history had other plans. Enter Stephen K Bannon. Officially Trump's chief strategist, insiders coyly describe him as the real president. Bannon is the former head of far-right US news site Breitbart. He's also a catastrophist, convinced the US is in the beginning of an existential civilisational war. Everything is part of that conflict. He has predicted war with an expansionist China in the South China Sea, but his main bête noire is what he describes as "the new barbarity" – a virulent, swelling Islam that threatens to undo centuries of Judeo-Christian progress.

Bannon's apocalyptic world-view is informed by various meta-theories. Huntington's is the best known, though Bannon has not been explicit in championing him, unlike Michael Flynn, Trump's most trusted adviser until he got caught out sailing too close to the Russian sun. The disgraced former National Security Adviser referenced the "clash of civilisations" in various (subsequently deleted) tweets about the US war with a "messianic movement of evil people". Flynn also lumped China and militant Islamists into a joint anti-West conspiracy, parroting the emerging "Sino-Islamic" alliance conjectured by Huntington.

Former CIA director and commander of US operations in Afghanistan and Iraq David Petraeus warned against such rhetoric when he testified before the US Congress earlier this month. Petraeus beseeched the new administration to "remember that Islamic extremists want to portray this fight as a clash of civilisations … we must be very sensitive to actions that might give them ammunition".

Petraeus doubtless had his successor in mind. The new CIA director, Mike Pompeo, has in the past evinced a Manichean view of the world and come close to predicting a civilisational holy war. Politics, he once exulted, is "a never-ending struggle … until the rapture". Whether anyone in Trump's administration is listening to Petraeus is doubtful. Their canvas is wider than anyone predicted.

Fear and National Identity

The full title of Huntington's book is The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. It's the second part that echoes loudest in Trump's already infamous executive orders — his policies on Muslim immigration, the Mexican border wall, cancelling the Trans-Pacific Partnership, sabre-rattling on China and Iran and unsettling Europe.

This is not to say Huntington is a reliable guide to understanding all of Trump's early moves. Fights with Europe are hardly a recipe for civilisational solidarity. Yet it is to the deeper assumptions underlying Huntington's theory that hardliners in the White House seemingly turn for illumination.

This article first appeared in the Business Day.