News

How to Topple Authoritarians — A Playbook

The leaders of opposition parties and civil society movements must develop a 'democracy playbook' for elections that goes beyond simply running against the government. They need a vision that both differentiates them and provides citizens with a good reason to vote for them.

The veteran Ugandan opposition leader Kizza Besigye was placed under effective house arrest on 12 May in Kampala after he attempted a protest walk in the city against skyrocketing commodity prices. It was the latest in a long history of attempts by the Ugandan regime to intimidate and coerce the opposition.

'It's very difficult,” says Dr Besigye, “to topple a regime backed by its military in a democratic election. They have all the advantages, all the levers of power, and never let go.”

Besigye knows better than most.

A medical doctor, he served in Yoweri Museveni's National Resistance Movement, which he joined in 1982 at the age of 25, as Museveni's personal physician.

When the National Resistance Movement (NRM) came to power in January 1986, he was appointed minister of state for internal affairs and later minister of state in the president's office and national political commissar. He had his first source of disagreement with Museveni in the latter post, over corruption.

Shifted to the Uganda People's Defence Force, as a serving colonel in 1999 he authored An Insider's View of How the NRM Lost the Broad Base.

“Our second source of disagreement was over the management of the 'transition',” says Besigye.

“He was intent on perpetuating the transitional arrangement (and leadership) and manipulating the constitution-making process to achieve that.”

Court-martialled, he left the army and ran against Museveni in the 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016 presidential elections. Each of these was characterised by irregularities, with even Uganda's own courts finding rigging and disenfranchisement in the 2006 poll.

The Commonwealth Observer Mission to the 2016 election, headed by former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo, noted that the process “once again” fell short of meetings democratic benchmarks.

Jailed countless times

In 2006, “I was nominated from prison and only got bail a month from voting day”. Besigye has also been under house arrest for months at various times.

He was detained three times by police during the week of the February 2016 event, and spent three months in jail after the election. This perpetual harassment would wear down lesser men.

He is not alone.

Although Besigye did not contest the January 2021 poll, the popular reggae artist Bobi Wine and his National Unity Platform ran Museveni close, indubitably closer than the official results showed.

Although the Electoral Commission declared Museveni to be the winner, again, with 58.64% of the vote, the process was described by the US government as “fundamentally flawed” when “coupled with the authorities' denial of accreditation to observers”.

Human Rights Watch reported the election was “characterised by widespread violence and human rights abuses”, including “killings by security forces, arrests and beatings of opposition supporters and journalists, disruption of opposition rallies and a shutdown of the internet”.

The European Union did not send observers to Uganda, as their recommendations from the 2016 election were not implemented, including reform of the Electoral Commission and transparency of the voting process.

Wine was arrested several times, manhandled and placed under house arrest. When his supporters took to the streets, more than 100 people died and more than 500 were injured.

Yet the US government has provided more than a $1-billion annually in aid to Uganda, of a total of more than $2-billion and even more if peacekeeping support to Ugandan forces in Somalia and South Sudan is included along with Kampala's share of regional humanitarian assistance.

Little wonder that when Wine was asked how the US might best support democracy in Uganda, he replied: “Don't pay our oppressor.”

Besigye and I met in Lusaka. Doesn't the change of government at the polls in Zambia in August last year — from the populist Edgar Lungu to businessman-turned-politician Hakainde Hichilema — give him hope?

“Yes, but the military in Zambia was not the means by which Lungu came to power. It remains relatively neutral, which is not the case in Uganda.”

The same, he points out, is the case in neighbouring Malawi, where the armed forces have routinely upheld the constitution in various changes of government, most recently from Peter Mutharika to Lazarus Chakwera after the 2020 election.

Finding the means to deepen democracy is a question for much of Africa, where the number of countries judged (by Freedom House) as “free” has fallen from 12 to just eight (of 54) over the past 15 years, with now just 7% of the continent's population living in such societies.

This trajectory is in line with global trends, as the share of the world's population living in free environments has halved to just 20% over the past 15 years as authoritarian practices proliferate.

And yet the Ugandan example applies especially to countries where national liberation movements remain in power, including Mozambique, Tanzania, Angola and Zimbabwe in southern Africa.

Of the handful of cases where challengers have unseated incumbents in African elections, there have been none among the more recent liberation movements.

How might democracy prevail?

To confront this, and ensure democracy succeeds, democrats have to deliver and win the vote between elections.

In part, this depends on leaders of opposition parties and civil society movements developing a “democracy playbook” for elections, which goes beyond the justice of simply running against the government.

Oppositions have to possess a vision that both differentiates them and provides citizens with a good reason to vote for them.

While fomenting splits in the ruling party, in part by assuaging the military, they need to build their own broad base of support.

There is a need, too, for democrats — within and outside government — to establish a narrative that transcends the boundaries of identity, particularly given the youthful nature of Africa's populations.

Ukraine's recent crisis offers some pointers as to what is possible, albeit in a different context, in establishing a clear narrative (in this case, of resistance) in the face of seemingly impossible odds, centring on a combination of patriotism, values and leadership.

Clarity and consistency of purpose and message are the key takeaways from President Volodymyr Zelensky's success.

Ukraine also emphasises the role that outsiders can play — both through negative (sanctions) and positive (aid) measures — if sufficiently motivated.

The first rule for outsiders — to take the lead of Bobi Wine — is that they should do no harm. They must avoid being played, and at the same time be cognisant at least of the trade-off between democracy and their own ideas of stability.

Similarly, they need to avoid being exploited by authoritarians with a well-developed election playbook. African observers have a particular responsibility, not least because they are often seen as more credible.

Beyond elections, donors must have a clear-eyed view that elections are a necessary but insufficient condition for democracy, and they need to focus on the conditions between elections.

In essence, donors should not allow their short-term interests to trump longer-term strategic values.

This reflects a crisis of conscience within the West, where “tribal partisanship, media polarisation, uncompetitive elections, the death of bipartisan compromise, political disengagement, economic decline, rising inequality and demographic change imperil democracy”, writes Brian Klaas in The Despot's Accomplice.

“But the storm has also made landfall on Western foreign policy. It is causing politicians and diplomats to downgrade or eliminate the promotion of democracy in Western engagement with the rest of the world.”

With Trump it was worse still, he says, “not just a lost appetite for democracy — it's an actual hunger to promote and praise ruthless authoritarian regimes”.

Global power shifts

And as the West has turned inward in the promotion of such values, “the Chinese dragon and Russian bear have been more than happy to swoop or lumber into the ensuing influence vacuum, giving rise to a meaningful and rapid shift of global power”.

Western donors have constantly maintained this view towards African regimes out of a cocktail of strategic interest, fear of rivals, cynicism and a predilection for stability over principle. Just like there are few governments that business does not like, there appear to be even fewer that donors can't find an excuse to aid.

This may help, for instance, to explain Washington's relationship with South Africa, where it is apparently so used to being dissed by Pretoria, that it pretends everything is fine. Disdain seemingly breeds a perverse dependency.

Voting patterns in the United Nations are one indication that South Africa has had a major problem with the US, its second-largest trade partner and largest investor, for some time.

Between 1994 and 2018, for example, the annual voting coincidence in the UN General Assembly between South Africa and the US averaged just 26%. It declined from the mid-30s under Mandela and Clinton in the 1990s to the teens under Mbeki-Bush, the low twenties during the Obama years, and 18% for 2017.

On human rights, voting overlap peaked at 62.5% in 1995 and reached its nadir at 8.3% in 2013, early in Obama's second term.

On issues of economic development, the coincidence of interest was just 8.2%. By comparison, South Africa voted with China most of the time: in the high eighties and early nineties, averaging 89.1%.

Even the most quixotic American president would have to realise that the ANC does not like them or share Washington's worldview and ideology, whatever the administration in power.

Yet for all the mutterings about Washington tiring of Pretoria's obvious dislike and disregard, the US carries on regardless, preferring to see the ANC as a schizophrenic actor, caught between political radicalism and economic rationality.

Washington behaves like a battered spouse towards Pretoria, believing somehow that relations will get better, common sense will prevail and that its love will eventually be requited.

This also poisons relations with the official opposition, with whom it maintains barely lukewarm relations, in so doing neglecting an important mechanism for domestic political accountability and Washington's own leverage.

How many votes in the UN will it take, one has to ask, until the US gets the message?

It's not just South Africa

In Uganda, Lt-Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba, the commander of Uganda's land forces and son of Museveni, tweeted support for the Russian invasion of Ukraine: “The majority of mankind (that are non-white) support Russia's stand in Ukraine”, he wrote, adding: “Putin is absolutely right!”

Opposition leaders in Uganda are now concerned about how to prevent a coronation of Kainerugaba, who recently went on a major “Team MK” political branding campaign to mark his 48th birthday.

And yet Washington remains largely publicly schtum on what amounts to a human rights foreign policy aberration. No donor is willing to explicitly calibrate African aid by democratic standards.

A failure to do so by democracies can only undermine perceptions of their power in a continent ever-willing to play to racial and other stereotypes. In so doing, long-term democratic governance is held hostage to short-term notions of stability.

If only actions had consequences

For their part, African domestic actors have to take a leaf out of the ANC's struggles in South Africa, and be more forthright in calling for external intervention, including sanctions as a tool of change.

The opposition in Zimbabwe has been reluctant to do so, for instance, given that they could then be seen to be acting against their own people's best interests, at least in the short term.

And yet in the longer term, the absence of change and the presence of a trickle of funding has ensured that the pain simply endures.

There is a similar dilemma in calling for street protests. As Tendai Biti notes, this was one of the toughest decisions Morgan Tsvangirai had to make as leader of the Movement for Democratic Change, “as it endangered people to a regime that would shoot without hesitation or remorse”.

There is a further constraint, Biti notes, on popular protest as an option, along the lines of Ukraine's 2004 Orange Revolution, or the 2014 Euromaidan protests.

“These were middle-class revolutions, where people have food, have transport, have resources. Most of the African circumstances are very poor, where people don't even have the next meal.

“Africa creates the conditions of state perpetuation, where failure gives life to a failed regime.”

Poverty makes political struggles that much more difficult, as does ignorance. Yet without a change of direction, the best Zimbabwe can hope for is a state of continuous reproduction of state violence, economic decay and failure itself.

This leads to a policy dualism, with the opposition calling privately for sanctions to be imposed while publicly appearing to reject such assumptions even though they are willing, at times, to call their supporters onto the streets. To do otherwise against a regime willing to unleash military force seems unrealistic.

But it is a long war — build a credible opposition, is Biti's answer. He argues that you cannot have the opposition mirror the regime, otherwise there is little motive for replacing them. And, he adds, “this is not just about money given by donors. Rather it's a question of agency of locals”.

The case for democracy

Democracy is important to the West since it is the great differentiating feature in their offer to Africa from China, Russia and others.

Across the 30 countries that Afrobarometer has surveyed consistently over the past decade, democracy is also what the majority of Africans prefer as a political system.

In the most recent poll, seven in 10 Africans say that “democracy is preferable to any other kind of government”.

Large and steady majorities consistently reject authoritarian alternatives, including military rule (75%), one-party rule (77%) and one-person rule (82%).

Democracy is thus not a peripheral interest to the West, “a distraction” from security, stability and economic growth, as Klaas notes, but rather its key selling point.

To support it, there should be a clearer calibration of the scale of reward — measured by access to trade, capital, technology and training — for democracies, not least since there is a clear empirical correlation between the health of African democracy and specific economic performance.

Overall, insiders need outside allies in their fight against authoritarianism. But they should learn not to be too cheap a date, and need to push back against the hypocrisy of donors in terms of their own values.

And this should not neglect, again, what insiders can do between each other.

There is a need to align tactics and strategies across Africa's opposition movements, which have been notoriously divided and thereby ruled.

Comparing notes extends to funding strategies, and in linking with democratic movements outside, particularly those engaged in the battle against authoritarianism.

Making common cause should be a default principle for oppositions, inside and outside Africa.

In sum, democrats must work even harder — and make tough choices — to win contests against authoritarians. And the West has to prioritise democracy promotion if it is to seduce African populations.

This article originally appeared on the Daily Maverick

Up next

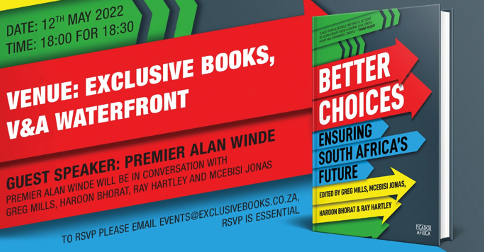

Upcoming Events...

11 May 2022