News

How much could Coronavirus cost the SA economy? A preliminary estimate

As we enter three weeks of shutdown, only one thing is certain: the impact of COVID-19 will be felt for a long time to come.

Former Researcher, The Brenthurst Foundation

Associate Researcher, The Brenthurst Foundation

Research Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

The cost of the coronavirus pandemic will depend on the length and severity of the virus. In South Africa, and elsewhere, much will also hinge on the success of the various economic resilience and recovery strategies. With the current lockdown, SA stands to lose a large share of three weeks’ worth of GDP, or R300-billion. .

Global pandemics don’t come cheap.

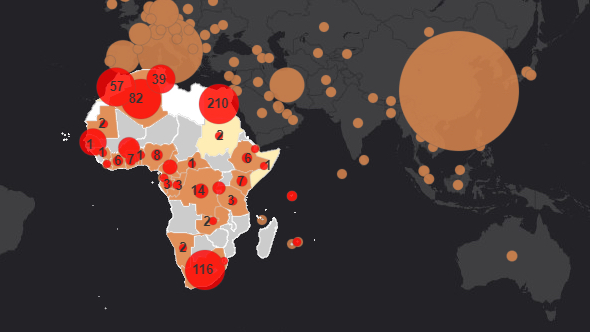

The HIV/Aids pandemic is estimated to have shaved between 2% and 4% off GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa. The annual cost of ‘flu is estimated at between 0.2% to 2% of global income, totalling US$570-billion. And the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic was estimated by the World Bank to have cost about 12% of the combined GDP of the three worst-hit countries: Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

But none compares to the depth and breadth of Corona. Over the past week alone the related stock market crash has wiped $9-trillion in values. And the bourses are still shaky. Lower global GDP growth could cost an estimated additional $2-trillion. The upcoming lockdowns in major economies threaten even more catastrophic impacts.

Morgan Stanley, for example, predicts the US economy falling by 30.1% in April-June. Goldman Sachs, which expects a 24% drop in US output during the next quarter, also anticipates the world economy to contract by 1%, a larger decline than during the 2008-09 financial crisis.

A global recession looks unavoidable.

Even before the crisis, SA’s economy was in a precarious position – especially with a technical recession (two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth) after a decline of 0.8% in the third quarter of 2019. Growth was just 0.4% in 2019 and was predicted by the IMF – before COVID-19 snowballed – to be just 0.8% this year.

Now South Africa looks likely to take a severe economic hit from the virus, well beyond the price of treating the infected. How might we estimate the cost of a global disease on the local economy?

This, of course, depends on what happens with the disease and the nature of our public and private responses.

The rapidity of the spread of COVID-19 appears much faster than SARS which ultimately infected as many as 1.5 billion globally and caused upward of 250,000 deaths. Some believe COVID-19 will phase out within six months like it did for SARS, and the markets will correct themselves in the second half of the year. The (unquantifiable) cost of global panic is more difficult to take into account, especially in the era of fake news, with the virus having a much larger global reach.

Many are thus unsure of how widespread, persistent and severe the impact will be on financial markets and national economies.

Prior to the spread of COVID-19, persistent electricity shortages, revenue shortfalls, mounting debt and low consumer spending all contributed to the low South African GDP growth forecasts, all things being equal. But of course, all things are no longer equal.

The Reserve Bank’s decision to cut interest rates by 100 basis points is expected to help stimulate demand somewhat, although this effect is unlikely to be realised if savings to consumers will not be spent. Demand could in these circumstances decline further at a time when consumer and business confidence is already at an all-time low. Any further decline in people’s willingness to spend and invest might temporarily alleviate exchange-rate pressures on the balance of payments, but local businesses will also suffer, particularly the 2.5 million or so Small and Medium-Size Enterprises, responsible for two-thirds of employment.

All of this has led the SA Reserve Bank to forecast a 0.2% contraction for 2020, a figure that accounts for anticipated weaker demand for exports and domestic goods and services, and disruptions to supply chains and regular business operations. But specific – and some subsequent – objective conditions may drive this estimate lower still.

This seems to be true in the case of Sasol, contributing in 2019 nearly 5% of South Africa’s GDP. The company’s share price has tanked by about 50% and continues to fluctuate, reflecting the nearly 70% slump in the oil price during 2020.

Rather, at this point, including the impact of Sasol, growth is closer to -0.3%.

Next, consider China’s massive influence over our economy: As PwC economist Christie Viljoen has put it, “For every percent that the Chinese economy cut, the impact on South Africa is a decline of around 0.2 percentage points.”

China is currently SA’s largest trade partner, with $17.1-billion in exports in 2017. The next largest export destination is the US at $8.1-billion. China provided imports to the value of $15.6-billion in 2017, with the next top import market Germany at $7.2-billion. China’s economic growth outlook for 2020 was, prior to the crisis, estimated at 6%. This may now be 5% or lower, depending on the duration and severity of the virus.

Chinese growth contraction is likely, absent necessary and successful stimuli, to have a disproportionate impact on minerals’ exports, comprising one-third of SA’s exports to the PRC, some $6-billion in 2019. The 2008 financial crisis saw a 50% reduction, for example, in Bloomberg’s commodity price index. Now the index is at its lowest level at any point in the last 30 years. A mere 5% loss in the value of SA’s mineral exports to China, will wipe off $300-million, or more than R5-billion at current prices.

The downward pressure on tourism is likely to add further to these woes. This sector contributed 8.6% to SA’s GDP in 2018 and was responsible for 1.5 million jobs.

A ban on external travel from China is likely to wipe out the flow of tourists. On average 95,000 Chinese tourists visit SA, spending an average of R15,000 each. Already the popular summer season and peak Chinese visiting times (Chinese New Year in January/February and the annual holidays in May/June) are effectively passed. We can assume a 25% decline in tourist numbers – 19% greater damage than from the SARS outbreak – though this may be much higher, not least given SAA’s suspension of international flights until June. But even at the 25% contraction, SA could be at risk of losing upwards of R35-billion in foreign currency spending.

In telecommunications, China supplies about 85% of South Africa’s mobile phone imports, the nation’s largest import category by value. Any disruption in this flow could be anticipated to have expensive knock-on effects on the sector and the broader economy.

In the automotive sector, February saw weak motor vehicle export sales at 30,832 vehicles, a decline of 8.4% compared to 2019. While difficult to estimate future import/export sales, COVID-19 is continuing to disrupt supply chains and affect manufacturing operations around the world, including SA’s domestic manufacturing which declined by 0.7% in February.

Together these factors – mining, manufacturing and tourism in particular – could prune at least another 1% off GDP growth forecasts, increasing the contraction to -1.3%.

And then the big one. With the current lockdown, SA stands to lose a large share of three weeks’ worth of GDP, or 5.8% of R5.3-trillion, or R300-billion.

Even if only half of this 21-day chunk is lost, in a reasonable best-case scenario COVID-19 could cost SA’s economy 4.2% of GDP growth – R220-billion (at 2019 prices).

There are far worse and yet still reasonable scenarios.

Without the right set of actions, the already-struggling SA economy could head into recession with a catastrophic scenario of debt downgrades, manufacturing sector collapse, and sky-rocketing unemployment. This would place huge pressure on the tax base and government’s already weak abilities to deliver and, above and beyond, offer a stimulus package. In this scenario, the country could have to turn to the outside world (such as to the IMF) for a bailout, which could prove as politically destabilising within the ANC as it is economically practicable, tensions which could be worsened by a steep rise in inequality as job losses bite. If such political tensions were to be countered by increasing policy radicalism and populism, a vicious and downward spiral could ensue.

Ultimately, the cost of the pandemic will depend on the length and severity of the virus. Much will also hinge on the success of the various economic resilience and recovery strategies, in SA and elsewhere. The US and UK have already announced spite of stimulus packages of $1-trillion and £350-billion respectively. As with the 2008 global recession, quantitative easing in the US and Europe could positively affect the SA bond market, for example, so long as SA’s interest rates remain higher.

There may be an upside scenario, where the country gets behind the leadership, where a stronger sense of national unity emerges, including a fresh social compact between business, government and labour, and where there is a new impetus and clear agenda for reform.

There are signs of such an upside scenario in the outpouring of public support for President Cyril Ramaphosa’s measures. Keeping money flowing to employees is part of the answer, particularly in the resilience phase, and keeping those businesses alive is imperative for recovery. Much will depend on how state departments especially health, transport, home affairs and the security forces will conduct themselves. If nothing else, the commitment of the Reserve Bank to quantitative easing by buying up government bonds speaks to the scale of the crisis.

The same advice is likely to help companies – and countries – get through COVID-19 as the Global Financial Crisis a decade ago: Maintain a long-term mindset, remain calm, invest in relationships, stick to a never-ending path of improving competitiveness and keep a steady tempo of reforms.

At this juncture, as we enter three weeks of shutdown, only one thing is certain: the impact of COVID-19 will be felt for a long time to come.

This article was originally published on The Daily Maverick.