News

Five Key Takeaways from South Africa’s 2024 General Elections

Listening to political leaders and commentators, you would have thought that the pre-election polls were a vast conspiracy aimed at cynically manipulating the vote. It turns out that (most of) the polls were spot on.

Research Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

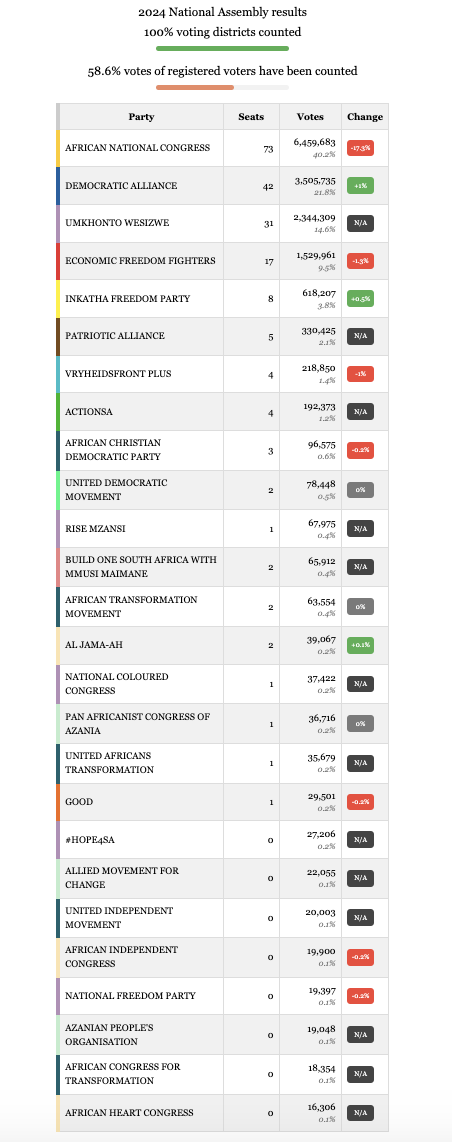

The voters have had their say and, as predicted by The Brenthurst Foundation in March, the ANC has been cut down to about 40%, with the DA the only established party to show growth, although this growth was limited due to a thousand cuts by tiny parties.

The rise of MK — also predicted in our March poll to emerge as the third-largest party — has created a new populist dynamic, although some of its growth was at the expense of the EFF.

As the coalition talks get under way, here are five takeaways from the 2024 election:

- Democracy works

The first and most important takeaway is that democracy works. The ANC, riding on the coattails of Nelson Mandela and its Struggle mythology, was able to dominate power for 30 years, but when it failed to deliver on the promise of a new, economically successful South Africa that created opportunities for all, the voters punished it.

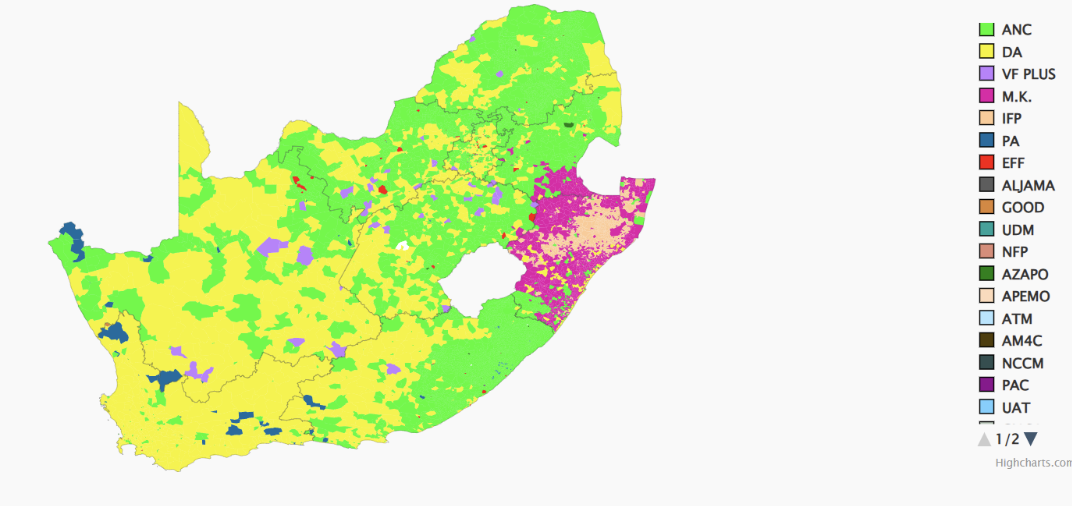

This is what democracy is all about — the capacity of the people to decide who they think will best run the country in their interests. They chose the ANC, then the DA, then the MK party, the EFF and, in fifth place, the IFP.

The message of consolidation around these parties was strong, with the five sharing some 90% of the vote. The electorate clearly supports consolidation around the major parties and has rejected the plethora of new, small parties which are frequently personality-based and lack strong policy differentiation from the larger ones.

While these parties showed strongly on social media, when it came down to placing a cross on the ballot paper and when organisational substance mattered over digital form, the big five took the day.

A statistic that illustrates this starkly is that 1.31% of ballots were spoiled, but the following parties were among 45 that got fewer votes than that very low threshold: ActionSA (1.2%), ACDP (0.6%), UDM (0.5%), Rise Mzansi (0.4%), Bosa (0.41%), ATM (0.4%), and Al Jama-ah (0.2%).

While democracy has triumphed, it is by no means consolidated. The coalition discussions that have begun will determine which combination of parties rules South Africa for the next five years. There are three clear scenarios here:

- An ANC/DA/IFP coalition around shared values of constitutionalism, the rule of law and sound fiscal policy;

- An ANC/MK party or EFF coalition around a shared populist agenda to deprioritise (or, in MK’s case, do away with altogether) the Constitution and to grow the state at the expense of private property and business; and

- A minority ANC government that governs with the support of one or more other parties when it comes to passing budgets and the like.

A coalition is not only about policy and the effectiveness of governance. It may determine whether democracy survives. The coalition choice will set South Africa on a trajectory towards economic growth and development or on a Zimbabwe-style slide where democracy itself will be imperilled, perhaps marking the election of 2024 as the last properly free and fair one.

The composition of the coalition will determine whether tribalism takes a firmer grip on South Africa’s politics. The role of Zulu identity is much noted; less so is the relationship between the ANC and its Eastern Cape support base. Diversity among the coalition members would help to mitigate the tribal and racial dimensions.

- There is a participation crisis

While democracy worked on election day, there are serious warning signs that it is on weak foundations.

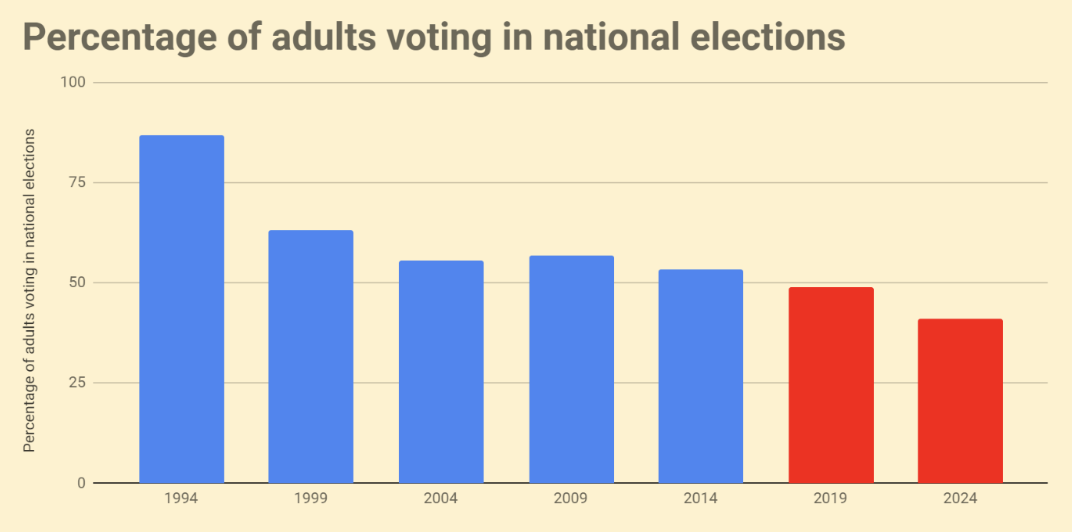

Electoral participation hit rock bottom on 29 May with a shade over 40% of South Africans over the age of 18 choosing to vote. The number of adults participating dropped below 50% for the first time in 2019 and has now dropped substantially once again.

This lack of participation in formal politics presents democratic institutions with a crisis of legitimacy as almost 23 million adults sit on the sidelines, disillusioned with the power of the ballot box.

The absence of civic education and the toxic public discourse which holds that elections make no difference are partly to blame.

All of this was not helped by the somewhat shambolic management of the voting by the Electoral Commission (IEC). Long queues, which ought to have been anticipated and solved, discouraged many who had decided to vote but did not wish to spend hours waiting for their turn.

In addition, confusing ballot paper choices with three papers, two marked “provincial” although only one was for the provincial legislature, did not help.

The fact that the additional ballot paper was occasioned by the decision to allow independent candidates — not one of whom was elected — is tragic and must be addressed.

The portents for the next election are bad, as those who found themselves queuing for hours will be less inclined to turn up next time.

The underfunding of the IEC and its lack of proper preparation to anticipate and plan for on-day logistical challenges need to urgently be addressed.

- A referendum on foreign policy

With its domestic cupboard bare, the ANC turned the final phase of the election into a referendum on foreign policy, adopting a high-profile, ultra-pro-Palestine position. President Cyril Ramaphosa even abandoned the ANC’s long-held support for a two-state solution, chanting “Palestine will be free from the river to the sea” in the final days of campaigning.

The objective appears to have been to unseat the DA from control of the Western Cape. Instead, the ANC lost 13% of its support there and the militantly pro-Israel Patriotic Alliance gained ground at its expense.

South Africans want their country to work for peace, to bring reconciliation in conflicts and not to become radical partisans.

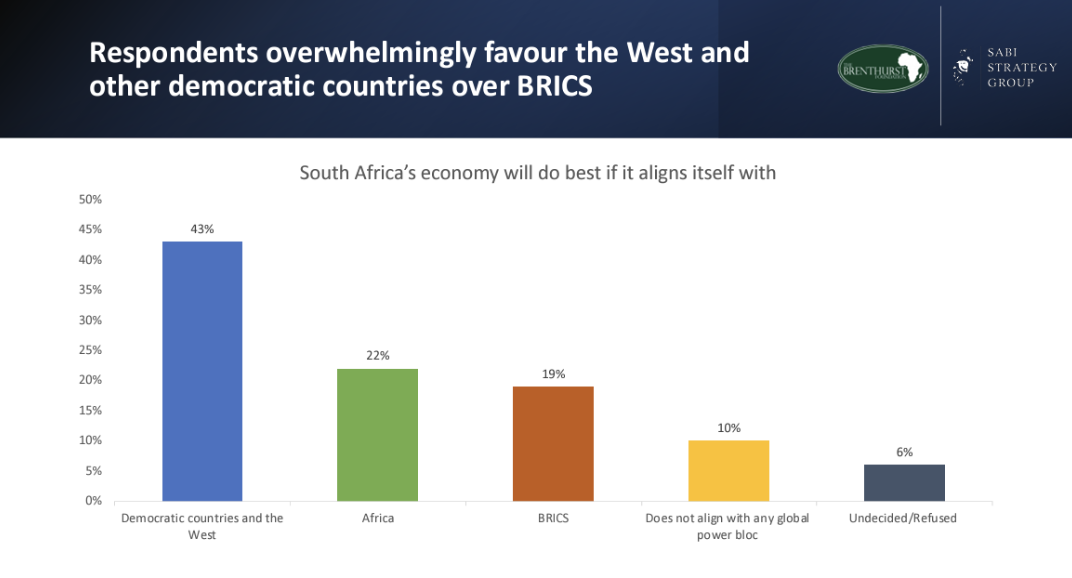

The ANC’s pivot away from the West and towards Russia, Iran and other undemocratic countries alienated voters. When asked if they would be more or less likely to vote for the ANC based on these policies, voters were clear in our surveys — they were turned off.

This was borne out at the polls.

Foreign policy has another dimension in terms of how the external world responds to this election outcome, and whether the response entrenches or weakens the power of constitutionalism and individual choice.

- Rejection of empirical research in favour of uninformed opinion

Listening to political leaders and commentators, you would have thought that the pre-election polls were a vast conspiracy aimed at cynically manipulating the vote. It turns out that (most of) the polls were spot on.

In the case of The Brenthurst Foundation’s poll, one politician even called for the regulation of polls because his party was being disadvantaged. In the event, his party received fewer votes than the poll predicted.

Other commentators, such as Business Day’s Jonny Steinberg, said there was “something strange” about The Brenthurst Foundation’s March poll which showed the MK party as the largest in KwaZulu-Natal and larger than the EFF at 13% in the national vote. This is perhaps forgivable since this was the first poll to measure the actual size of Jacob Zuma’s base and cappuccinos were being spilt across the country at the news.

Others such as Melanie Verwoerd in Daily Maverick wrote that The Brenthurst Foundation’s poll was questionable because of its “proximity to the DA”.

The efforts of the commentariat and the vast social media campaign to undermine the opposition did not, in the end, change anything because negative messaging only works when it coincides with experiences in lived reality.

Far more alarming was the deployment of a social media army to campaign for Zuma’s MK party, an intervention which appears to have produced strong results given that party’s weakness on the ground. Given the “lived reality” under failed ANC rule, the messaging was eagerly received and passed on.

Following the launch of the MK party, a clear decision was taken — probably by the funders of social media dirty tricks — to switch allegiance to it and away from the EFF as the main vehicle for “radical economic transformation” propaganda.

A report by the Centre for Analytics and Behavioural Change and Murmur found that “the MK Party appears to have mobilised the network and influence of an existing online community” to rapidly build a strong social network presence.

“The newly formed community, the ‘MK Party community’, appeared to have an immediate surge in interactions and engagement online, backed by a large number of followers.”

As coalition discussions began, a new wave of disinformation hit social media aimed at leveraging the ANC into a coalition with the MK party and/or the EFF and not the DA.

This assault on fact-based decision-making poisons the public space and pushes key actors away from rational decision-making.

The way forward

As South Africa approaches its biggest decision in 30 years, what is needed is faith in the democratic process and an understanding that we have entered new, uncharted waters where no single party dominates the political landscape.

This new environment requires a retreat from shallow, partisan positions and a return to embracing the democratic, nonracial and inclusive character of South Africa as spelt out in the Constitution. We must become, once more, a lodestar for democracy and a passionate advocate for accountability on the domestic and international stage.

The window has opened. In working out the selection of coalition options, political leaders have a stark choice: act to consolidate the democratic gains of 29 May or live with the consequences for decades.

This article originally appeared on the Daily Maverick