News

Courtus Interruptus? Don’t be Fooled, Putin’s Absence From SA May Only be Temporary

This, it is clear, was a decision arrived at because the government’s legal position was weak: South Africa would be in violation of its own law if it failed to arrest Putin. It was a decision arrived at with regret rather than moral fortitude.

Research Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

The wave of relief that washed over the country after President Cyril Ramaphosa announced that Russia’s Vladimir Putin will no longer attend the BRICS summit in person was palpable.

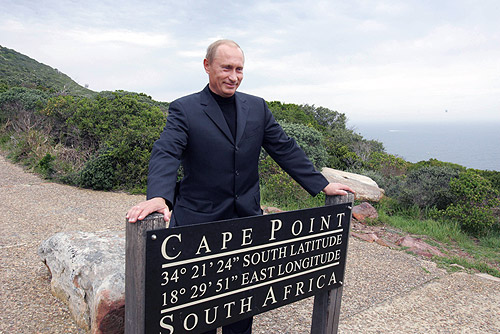

Putin, wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes related to the organised kidnapping of Ukrainian children, is a global pariah who is responsible for the invasion of Ukraine, an event which has triggered a deadly war in which tens of thousands have died.

It was clear to Ramaphosa that not only would South Africa not host the summit of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa) in November should the Russian leader visit, but that South Africa’s membership of Agoa would be at serious risk.

Sanity seemed to prevail, no doubt heightened by the decision by the Department of Justice to issue a warrant of arrest for Putin following a Democratic Alliance court action aimed at forcing the SA Government, no matter how weak-kneed and unenthusiastic it may be, to arrest Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin.

But the euphoria around Ramaphosa’s statement may be premature.

What is notable about the announcement is the absence of any criticism, however faint, of the Russian invasion and zero support for the arrest warrant itself.

This, it is clear, was a decision arrived at because the government’s legal position was weak: South Africa would be in violation of its own law if it failed to arrest Putin. It was a decision arrived at with regret rather than moral fortitude.

Ramaphosa said in his sparsely worded statement: “By mutual agreement, President Vladimir Putin of the Russian Federation will not attend the Summit but the Russian Federation will be represented by Foreign Minister Mr Sergey Lavrov.”

A subsequent ANC statement returned to fawning over Russia, saying: “The ANC notes the decision of the Russian government and looks forward to welcoming Minister Sergei Lavrov as one of the leaders of delegations from our BRICS partners. Minister Lavrov is one of the veteran foreign affairs leaders in the world and brings to the summit invaluable insights.”

Putin will apparently address the summit by video link, and will no doubt be received with the usual fawning, praise and reverence with which the South African government has always treated him.

The danger is that with the BRICS hullabaloo over, South Africa will find a new way to take the country to the brink with a new Putin crisis.

Ramaphosa has already publicly (mis)stated that South Africa wishes to withdraw from the ICC, a move which would give Putin — and other wanted war criminals — carte blanche to visit the country. His withdrawal announcement was withdrawn as it had been made prematurely, a case of courtus interruptus.

Failing that, there has been much speculation that the ANC will seek to pass domestic law that will exempt the government from having to arrest those wanted by the ICC, something which has been done by a range of countries seeking to hedge their bets with tyrants.

The problem with both of these possible paths is that they would open the door for Putin to visit South Africa without the interference of pesky human rights issues in the future. The outcome of such a visit — or, indeed, others wanted for heinous global crimes — would be, as we have learned from the present crisis, a substantial reduction in the country’s global standing and a reduction in its access to key markets for exports.

More than that, there is a matter of principle at play: the point is not that we should be doing what others do. Rather, we should do the right thing and take a stand on global human rights that is in keeping with our constitutional imperative.

It is no accident that the very first clause of the Constitution reads as follows:

“1. The Republic of South Africa is one, sovereign, democratic state founded on the following values: (a) Human dignity, the achievement of equality and the advancement of human rights and freedoms.”

This, and not the opportunistic calculations of a desperate political party, ought to be the cornerstone of our foreign policy.

This was recognised by president Nelson Mandela. On the eve of taking office as the first democratically elected president of South Africa in May 1994, Mandela penned an article for the November/December edition of the journal Foreign Affairs titled “South Africa’s Future Foreign Policy”. It remains the clearest articulation of a foreign policy framework consistent with South Africa’s choice to become a constitutional democracy that entrenched fundamental human rights.

Asserting that the country’s new government would “build a nation in which all people — irrespective of race, colour, creed, religion or sex — can assert fully their human worth”, Mandela outlined six “pillars” on which South Africa’s foreign policy would be based. The first of these was “that issues of human rights are central to international relations and an understanding that they extend beyond the political, embracing the economic, social and environmental”. The other five were:

- “That just and lasting solutions to the problems of humankind can only come through the promotion of democracy worldwide;

- “That considerations of justice and respect for international law should guide the relations between nations;

- “That peace is the goal for which all nations should strive, and where this breaks down, internationally agreed and nonviolent mechanisms including effective arms-control regimes, must be employed;

- “That concerns and interests of the continent of Africa should be reflected in our foreign policy choices; and

- “That economic development depends on growing regional and international economic cooperation in an interdependent world.”

Mandela went on to outline this vision of foreign policy built on the foundation of human rights and democracy, saying that “because the world is a more dangerous place, the international community dare not relinquish its commitment to human rights.”

It was under Mandela’s leadership that South Africa joined the ICC, precisely to join the community of global nations seized with eradicating tyranny and abuse.

The world has indeed become a more dangerous place. Rather than weasel our way around tyrants, now is the time to reassert human rights as the basis of our foreign policy outlook.

The other road is the highway to hell via isolation and economic decay.