News

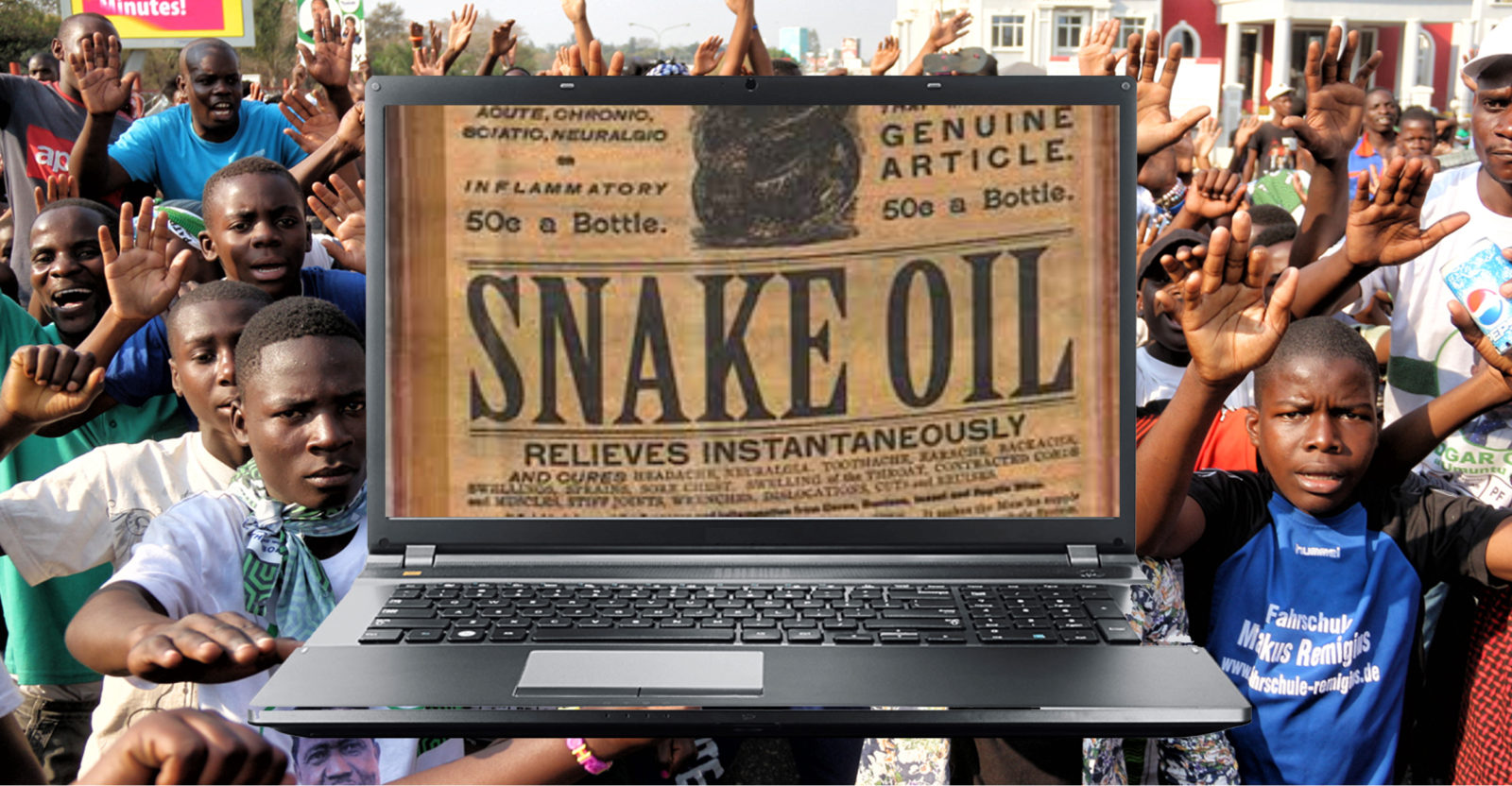

Beware the Digital Snake-Oil Salesmen

Technology is not the silver electoral bullet that it is made out to be, and nor are the consultants who claim to wield its power

With more than 20 elections a year in Africa, consultants are inevitably doing the rounds, promising the digital answer to promote candidates. But they need to be taken with a large pinch of salt, since some are no more than masters of fake news and digital fiddling – and they are no answer to the morning after the election night before.

The 50th anniversary of Moore’s “law” – that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles about every two years – marked an estimated trillion-fold increase in computing performance since 1965. The practical achievements are impressive. For example, the Apollo guidance system that took astronauts to the moon equates to the processing power of two games consoles.

With this amount of present-day firepower, it is unsurprising that digital means – and the consultants who profess to unlock their dark secrets – are today taken as a game changer in elections, enabling the careful (and sometimes controversial, as in the case of Cambridge Analytica) profiling of voters and their preferences.

Future technology, including virtual and augmented reality, looks set to influence further; making it imperative, apparently, to have its wizards on your side if you are going to win a democratic contest.

Technology, of course, has not only affected the way we conduct commerce but also the way we communicate. Technology, as Moore’s law illustrates, will continue to evolve, and to change the way we do things. This is best indicated in contemporary terms by the impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on manufacturing and, by implication, on the economies of countries and as a result, global politics.

In particular, 3D printing and broadband together look set to do for manufacturing what the internet did for information – in the words of Greek tech-expert Kyriakos Pierrakakis, “to decentralise and to democratise it”.

But technology is not the silver electoral bullet that it is made out to be, and nor are the consultants who claim to wield its power. It’s fashionable, but it’s often just bullshit, and a cover for nasty propaganda.

As the former Romanian prime minister Victor Ponta, who lost his run at president in 2016, wryly observes: “I have met 1,000 consultants who made Obama president, even 1,000 consultants who made Trump president, but I have never met one who failed in an election.”

Their cause is seldom helped by their tendency to be disparaging in the process about their clients and their critics.

Data on the electorate is undoubtedly important, as is its means of harvesting, but is not a solution in itself. It is a tool, enabling information to target the message.

And information on your opponent including how they operate and from where they source their funding, for example, can also assist, not least by heading off negative external influences. This is less information, however, than intelligence.

Technology, too, can be very useful in establishing systems of parallel voter tabulation, which reduce the scope for the tampering of results and, again, in providing focus to electoral effort.

But generally, as Ponta also notes, political leadership has “No capacity to receive all the information that [consultants] provide.”

None of this, however, is likely to stop desperate politicians spending vast sums believing that this will answer their prayers, even though any consultant, digital or otherwise, is constrained by the need to retain credibility which radical change risks undermining.

Thus even more important is the content of the message itself, how it is packaged and the generation of tactics as how to combat your opponent’s fake news, propaganda by its real term.

All of this requires channelling and managing consultants to the candidate’s advantage.

What makes a good message? This, experience teaches, is seldom based on a rational argument, but on more prosaic sentiments of fear, hate or hope. Moreover, the electorate want to hear stories than help to understand their circumstances, and to present a clear message for the day after – something, for example, that Hillary Clinton failed dismally to do.

There is a warning in all of this.

“Even if the ability to target groups,” says Pierrakakis, “has grown exponentially, the ability to generate messages has not.”

This places an emphasis today, perhaps more so than before given the digital clutter in the field, of being the storyteller rather than the manager of information or just the techie.

Then there is the need to deal with fake news – otherwise described as “segmented media”. The consensus seems to be on avoiding responding altogether and thus providing it with more media oxygen, and in building a direct relationship of trust with constituencies. But like drugs in sport, the technology to spot fake news is inevitably slower than the ability to generate and project it.

Another means is to raise the cost for the fakers and give them a bad name – to go negative not just on the opponent but, in the fashion of Bell Pottinger, the messenger.

All this suggests going back to basics.

With increasing volumes of news and opinions, more important than digital harvesting and targeting is likely to be the generation of a strategy for the day after, which involves much more than punting the candidate, but rather projecting a set of ideas.

“You need to do more than mobilise your base,” says Ponta. “You need to adapt to technology, yes. While we are told to polarise and mobilise our base against others, if you do this after the election, you will lose your country. I would strongly advise against this.”

The exact metrics and effectiveness of digital campaigns are largely unknown, even if the purveyors believe it enables their clients to get over the line first. One of the problems is that much of the available information about the impact of consultants, as Nic Cheeseman notes, is obtained from the consultants themselves, and they – surprise, surprise – have a vested interest in talking up their effectiveness.

In the worst cases digital electioneering is little more than a cloak to disguise the worst sort of vicious fake news content. And if nothing else, it is more mental than empirical: the candidates believe in themselves in having such a digital campaign.

Certainly if every candidate possesses a digital dimension, they will cancel each other out.

Technology may, in other words, make the difference between being first or second. But if you have no political message that goes beyond dissing your opponent, nothing will ultimately save you – even if you do win.

This article was originally published on The Daily Maverick.