News

Anyone Read Animal Farm? SA's Democratic Fragility and Four Scenarios

This week, South Africans go to the polls in what could be a historic election where the country shifts from one-party dominance to coalition rule of one or another stripe.

Former Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

Former Research Director, The Brenthurst Foundation

The election is democracy's sharpest tool, an instrument citizens use to decide who they think can best manage a R2.4 trillion budget so that the country moves forward and delivers a better life for all citizens.

Queuing up and voting is an empowering experience. Whether you arrive in a roadkill 4X4 or walk to the polling station, for one shining moment, you are the equal of your fellow citizens. The idea is that afterwards, a government takes office, closing that gap, offering more opportunities and firing up the economy to create work and progress for more and more compatriots.

Our election is likely to be free and fair, although there are rumours of war in KwaZulu-Natal as Jacob Zuma's MK Party says it won't regard a result which awards it anything less than two-thirds of the vote as legitimate.

But there are real concerns about the state of democracy that must not be brushed over, even as we celebrate voting.

For one thing, participation in democracy is weak and, even this "watershed" election might not fix that.

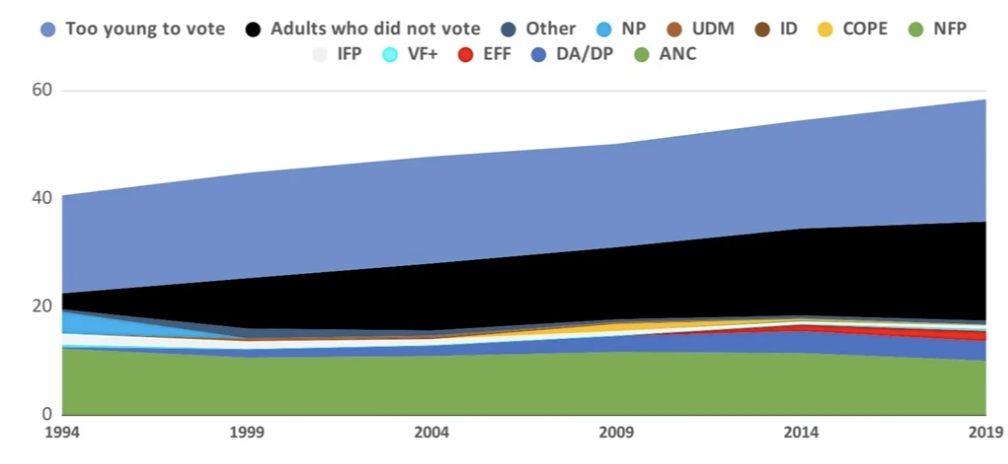

As the graphic below illustrates, a yawning chasm of apathy has opened up over the last 30 years of democracy. Fewer and fewer adults of voting age are participating in formal politics, and youth registration is abysmally low. This pattern of non-participation has grown as government's capacity to deliver has diminished and corruption has risen. It is fuelled by a deep cynicism, a view that "voting won’t change anything".

Apathy is the fastest-growing political movement in South Africa. The black area of the graphic shows this dramatically.

Nothing illustrates this better than the fact that more people voted in the national election of 1994 – some 19 533 498 votes – than in 2019, some 25 years later, when only 18 333 564 cast their ballots despite the population growing by 18 million in the same period.

Unsurprisingly, those voted in by this dwindling voter population have done very little about youth voter registration or about encouraging active citizenship, both of which are the feedstock of competitive democracy. They have been happy to preside over democracy's gentle slide into apathy because it serves their interests.

Over the last 30 years, only one of the arms of democratic government, the judiciary, can say that it did its job reasonably well. The apex moment and one where the credibility of the courts was underscored, was no doubt the Constitutional Court judgment read out by Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng.

Nothing summed up this outstanding moment for democracy better than Mogoeng's statement:

Constitutionalism, accountability and the rule of law constitute the sharp and mighty sword that stands ready to chop the ugly head of impunity off its stiffened neck.

The risk of apathy

Before we get too carried away, the judicial role has not been the perfect story. The weakness – and politicisation – of the judicial system has its share of the blame for the establishment of a situation of impunity. The failure to prosecute those identified as corrupt by the Zondo Commission is on its watch. The judiciary after all, comprises more than just the apex court.

However, while the judiciary was comparatively held, the legislature and especially the executive manifestly failed to deliver on the democratic promise. Dominated by the government, Parliament was admonished for closing ranks on Zuma, and it would later cover up for his successor, President Cyril Ramaphosa, putting aside recommendations by its own commission that there be an investigation into the mysterious appearance of tens of thousands of US dollars in the president's couch.

Just as there were dark spots in the judiciary's record, there were, however, bright spots in Parliament’s role given its role in continuing to highlight – amidst some theatre – Zuma's malfeasance.

But there's more. The executive has presided over infrastructural decay and a vast network of crooked contracts; the latter laid bare in excruciating detail by the Zondo Commission's inquiry into state capture.

Instead of moving to strengthen and grow democracy and democratic participation, the executive has apparently been happy to see the last of disgruntled voters as they have opted for apathy.

And, in another alarming turn, it has begun to turn its back on the democratic nations of the world in favour of a potpourri of dictatorships, autocracies and theocracies with abysmal human rights records and a penchant for imprisoning and murdering critics.

When South Africa joined BRICS, it become one of three democratic nations – Brazil and India being the other two – in the organisation dominated by Russia and China.

When the opportunity came for South Africa to lead the expansion of BRICs at the 2023 summit held in Sandton, Johannesburg, what did it do? It overlooked Africa's two largest democracies – Nigeria and Kenya – and instead chose to extend BRICS to Iran, the UAE, Ethiopia and Egypt, thus turning the body from a forum for enhanced trade to one antagonistic to democracy.

It was an alarming sign that democracy is no longer the loadstar of South Africa, which nowadays prefers the company of autocrats. New friends included Iran's hardline president, Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, the first person the South African government consulted after the 7 October terror assault on Israel.

When he died in a helicopter crash earlier this month, his citizens celebrated the death of a man known as the "Butcher of Tehran" with fireworks, but Ramaphosa said: "This is an extraordinary, unthinkable tragedy that has claimed a remarkable leader of a nation with whom South Africa enjoys strong bilateral relations."

There was not even the fig leaf of "although we may have disagreed about democracy" or a mention of the thousands imprisoned and executed under a violently theocratic regime.

Now there is a threat not only in terms of the deterioration of already ineffective governance, but worsening policy.

There are those on the ballot paper, such as the MK Party, ranked third in most polls, who are openly in favour of the repeal of the Constitution. Others want it amended and limited in scope. Some of these parties might end up as minority parties in a new government should the ANC choose to continue its populist trajectory.

Four scenarios

This lends itself to four scenarios around these twin-tracks of policy and governance, which we have mapped out in 'The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly – Scenarios for South Africa’s Uncertain Future'.

The first – the "Good" scenario – is the only one which provides light at the end of the tunnel – centres on the building of a centrist pact built on the Multi-Party Charter and the pragmatic bits of the ANC, which together could command as much as 75% of the vote according to the latest surveys.

For this scenario to eventuate would require swallowing some humble pie and the emergence of the much-talked-about but hitherto invisible "good ANC", which would place the majority of South Africans, not just its increasingly out-of-touch elite, fascinated with the power and its tantalising economic proceeds, at the centre of policy and implementation.

The good news is that we are part of the way towards the latter scenario through key provinces. It seems certain – as certain as one can be ahead of elections – that coalitions will run Gauteng and KZN, which with the Western Cape comprise nearly two-thirds of national GDP.

The provincial dimension may be just the segue needed to broker a wider national deal that puts the country first. And it's just such a deal that could save the Ramaphosa presidency from a legacy of disappointing indecision and governance failure which ends in a catastrophic tilt to the populist promise of redistribution. Of course, this "Good" arrangement comes with dangers, not least the threat of the ANC swallowing up the opposition once it has got its breath back, just as ZANU-PF did to the MDC in Zimbabwe. But overall, it is the only coalition alternative offering an improvement in governance and policy.

CLICK HERE TO TAKE OUR VOTE NAVIGATOR QUIZ

Animal farm nightmare

The second – the "Bad" scenario – comes in the form of an "Animal Farm" nightmare, where the ANC hooks up with populists who want the Constitution and/or private ownership of anything scrapped. The ANC, in combination with either the EFF or the MK Party – or both its mutant offshoots – will see a rapid descent into populism.

Ramaphosa's trademark dithering will pave the way for these populist forces to seize the public agenda and push him around. In this scenario, for tourists dipping in for a cheap holiday like those businesspeople seeking a quick flip, South Africa won’t seem such a bad place, save for those actually living and working there.

This scenario is more likely than most think. The ANC has already flirted with abandoning private property rights, it has launched the NHI without any funding plan and there are several powerful persons in its leadership who openly desire this outcome. In this scenario it is worth asking whether 2024 could be the last democratic election given all the signs: authoritarian friendships, shady funding, leadership impunity, rising violent crime and scant regard for parliamentary niceties.

"It'll never happen to us" and "we're too big to fail" are among the famous last words of many other regimes.

The "Ugly" scenario – can be summed up as more of the same as the ANC squeaks over the line with a shade over 50% and then continues with the status quo ante – of the prospect of little reform in the human and institutional software required for a modern economy, given the inherent loss of rent, while managing a weak fiscus as the effects of its unsubtle pivot to populism in the form of the signing into law of the National Health Insurance take hold.

The final scenario – the "Fistful of Cents" – sees the ANC fall below 50% but with sufficient votes to form a coalition with one or two smaller parties, possibly including the PA or the IFP. While policy can be expected to remain much the same, this can only lead to even worse governance given the inevitably highly transactional relationships likely with some smaller parties leading to, at best, limited reform.

When South Africans vote on Wednesday, we should celebrate democracy as we seek to build a better country with the choices that we make, but we must also pause to think about its fragility and what we can do to return our country to its democratic roots before voting itself becomes a charade.

This article originally appeared on news24

Photo: GovernmentZA Flickr