News

African Governments Must Bring Young People on Board for AfCFTA Trade Pact to Succeed

African governments need to earn the trust of young people if they are to successfully implement the African Continental Free Trade Area and ensure the participation of the largest population cohort on the continent.

Hailed as a key to unlocking rapid economic growth on the continent, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) has reignited hope that Africa will be able to realise its economic potential through a unified free trade area merging the continent’s 1.3 billion people.

The AfCFTA was established in 2019 when 54 member states signed it into existence. By October 2022, the Guided Trade Initiative, a pilot programme for trading under AfCFTA, was set up with eight countries.

The progress made in terms of setting up and implementing the AfCFTA and its supporting protocols over the last six years is commendable — especially in a context where leaders in Africa do not have a good track record of successfully realising policies that they promise to the public.

What is discouraging about the AfCFTA, however, is that it risks going down the same path as previously failed policies. This is because, as much political will as there is to implement it, public trust in institutions and governance is at a record low in Africa — especially among young people.

What further cements this lack of trust in AfCFTA are the bottlenecks in executing the necessary steps for AfCFTA to be truly operational such as harmonised standards and protocols for ensuring compliance, as well as the localisation of communication campaigns to raise awareness about AfCFTA and advocating preparation, training and usage among society’s most enterprising and vulnerable.

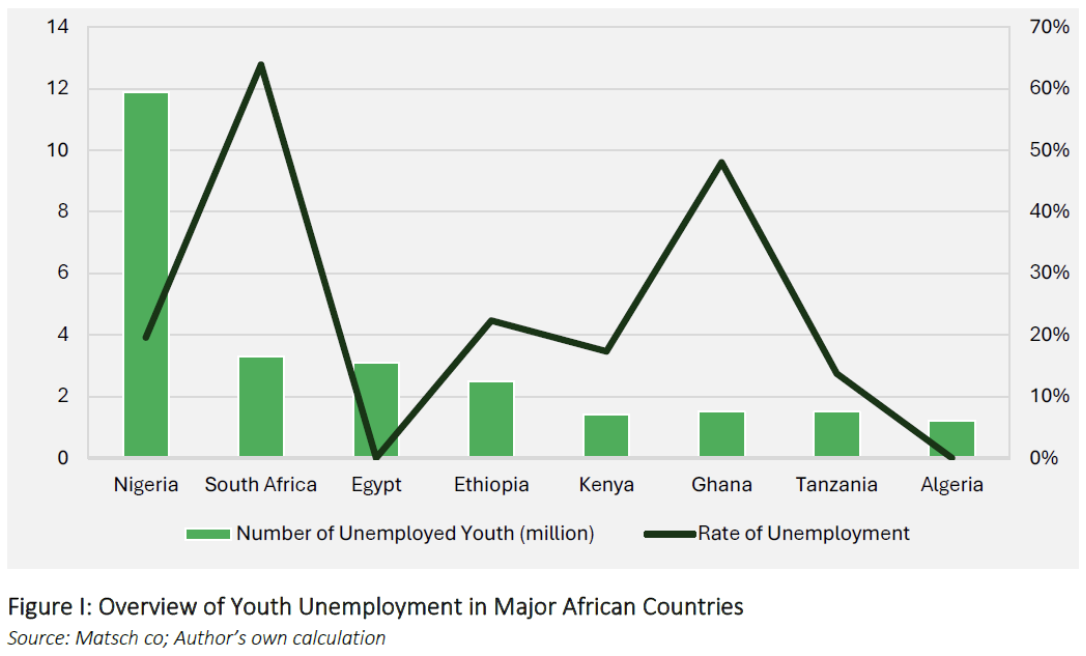

For decades, governments in Africa have failed their young people in deep and scarring ways. The greatest of these failures is evident in high levels of unemployment resulting from poor economic policies and governance records (see the image below of unemployment rates in Africa’s largest economies).

More worrying is the fact that most governments in Africa do not make a concerted effort to include and consult young people on public policy decisions, nor do they accept criticism from their young people.

In my study of the perceptions and experiences of trading under the AfCFTA, the common perception shared by interviewed youths is that they do not trust their governments to truly make the AfCFTA work.

One of the participants noted, “We do not have a track record. Where is the evidence that this thing is truly working?” Another participant said there was a lack of communication about AfCFTA at country level.

The question before African leaders and government administrators is: How then can the AfCFTA benefit the largest and most marginalised population on the continent if it is not being localised or advocated intentionally?

Earning the forgiveness and trust of young people requires a far more proactive response than signing and ratifying exciting policies. It requires practical good-faith efforts that can demonstrate to young people that the pattern of abusive governance is changing.

Proactive

First, individual states need to be proactive in their communication campaigns for AfCFTA. This policy has not been adequately publicised, using platforms like radio, in local languages, and through public debates. Communication also entails providing training, workshops and central offices that respond to questions related to AfCFTA.

Second, there needs to be reliable data that inform people about the opportunities available through AfCFTA and monitor the trends and patterns of trade under AfCFTA. Currently, the African Trade Observatory (ATO) has been earmarked for this task; however, information related to trade under the GTI is still unavailable, and there is no real-time dashboard for users to interact with and understand key performance indicators such as the value of exports, types of exports and imports, as well as information on how to be trade-compliant – especially as an informal business. In its current state, the ATO is simply not fit for purpose.

Third, young people need to be placed as the focus of the AfCFTA in local economies. This means that the needs and barriers that young people face should become the guiding tool for national frameworks looking to domesticate the AfCFTA as a way of life.

Local and national governments must work in partnership with the private and non-profit sectors to ensure that educational curricula are equipped to educate young people about the AfCFTA and its supporting protocols. Moreover, through various partnerships, governments must set aside a satisfactory portion of their national budgets and donations to eliminate structural barriers to trade, such as access to trade finance.

Last, bureaucracy needs to be eradicated to ensure greater efficiency in meeting AfCFTA compliance measures. Responsible governance requires clear, transparent, efficient ways of accessing public services. Bureaucracy has cost Africa billions in potential income as many choose to avoid doing business on the continent or find informal ways to do business. Instead of criminalising informality, there needs to be a more realistic approach to informality which includes cutting bureaucratic red tape.

If leaders in Africa want to overcome the constant reminder that “Africa has potential” and actually realise that potential, then they must be more proactive about leveraging the biggest population through meaningful acts of trust.

This article originally appeared on the Daily Maverick