News

Africa Needs to Keep Making Democracy Work Through Free and Fair Polls

This year has witnessed a host of elections in Africa – some good and some catastrophic. More elections are coming up in 2024.

What are the threats and challenges to democracy emerging from upcoming elections around Africa?

A useful analogy is the comparison between stagnant water and a flowing river. In a stagnant pool, water is still for long periods. Nothing moves, nothing breathes, and nothing grows. Eventually, everything rots, and the pool begins to smell. Very little survives in the pool.

However, in a river, there is movement, fresh water, and thriving ecosystems that grow and evolve. Business is done around the river, people can eat, and be transported – some even plan rituals around rivers.

If elections and democracy are working, they are like the river, allowing for dynamism, new life and new ideas. When there is a change in leadership and government – even from within the same party – new life, ideas and approaches are introduced, and new lessons are learnt, whether good or bad.

When elections fail, society stagnates and rot sets in.

Following a 14-year civil war, the Republic of Liberia set a course of post-war reconstruction and peace in August 2003. One of the policies introduced by President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who was elected after the civil war, was that of multiparty consultations within the constitution of the National Electoral Commission (NEC).

This policy recognised that the Liberian civil war had resulted from exclusion and political marginalisation. Although the NEC under President George Weah did not follow this precedent, the current electoral commission has been lauded for being honest and transparent in its decisions and processes.

One election observer from the Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy said that in some cases the Liberian NEC can be “too honest”. While the NEC has come under fire for poor communication with stakeholders, its commitment to honest and transparent processes is a strong reminder that dynamic politics and fair changes to government are only possible through intentional and clear processes.

Checks and balances

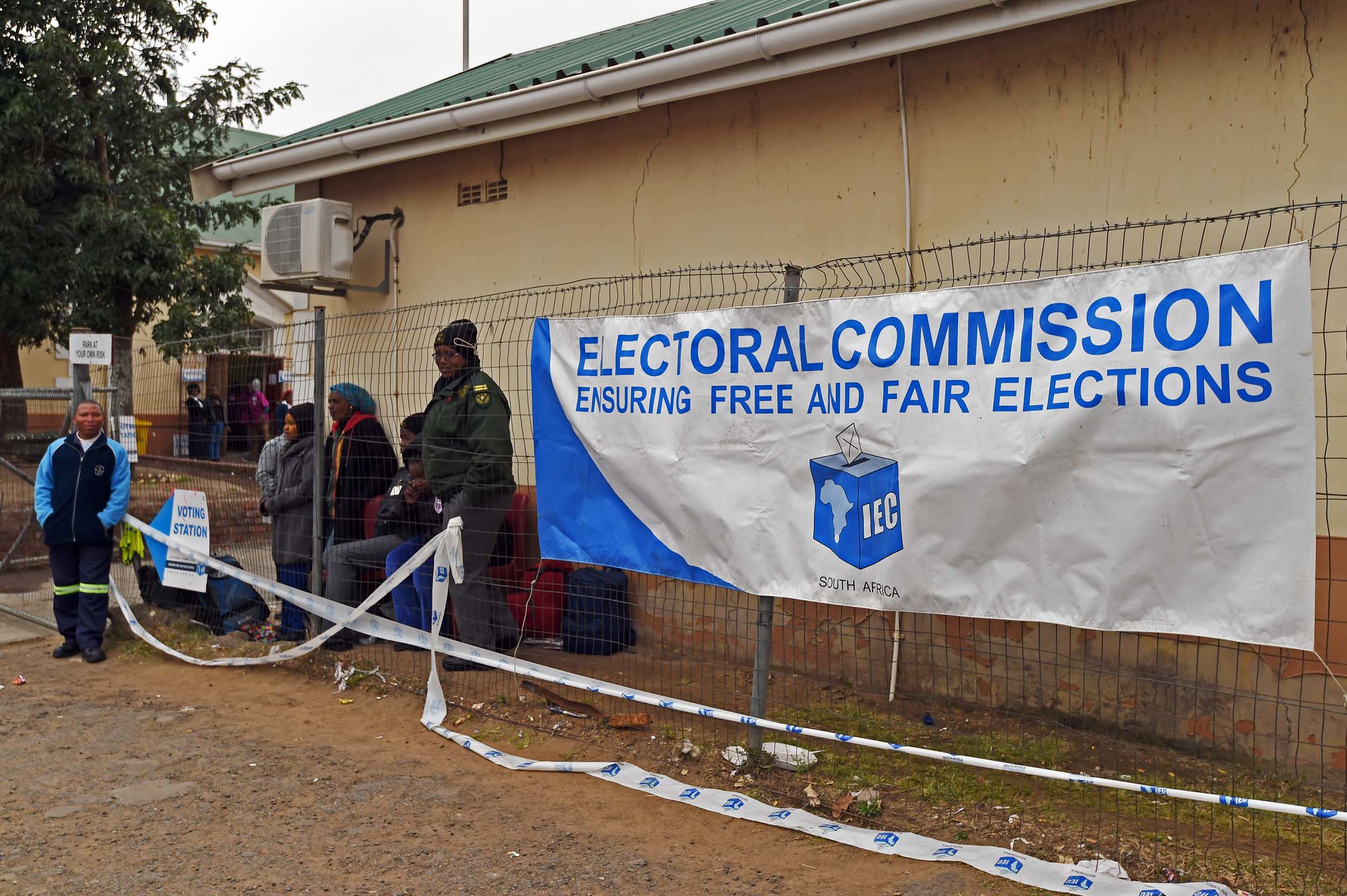

South Africa’s post-apartheid Constitution has seen successive democratic elections. Although dominated by one party, the checks and balances in place have so far kept accountability alive.

Civil society organisations and, in some cases, the judiciary, have stood up to abuses, most notably against the practice of State Capture under former president Jacob Zuma.

It is the commitment to new ideas and to fight for development and inclusion that led people like former Public Protector Thuli Madonsela to strive for justice and transparency in the face of one of the worst forms of corruption.

Of course, in competitive elections, there is a chance that leaders who are rogue, discriminatory and corrupt in their practices may take the helm.

This tests the ability of civil society, the media and independent institutions to prevent abuses, and underscores the importance of institution-building and institutional solidarity, which strengthens those who hold abuses in check.

The key word here is change. Change in leadership is a change in ideas and ultimately a catalyst for development and strong institutions.

On the other hand, when there is no change in leadership, and civil society and the judiciary are too weak to act, leaders stifle pathways for new life and new ideas – they hold on to old mistakes, approaches and ways of thinking. They stifle growth. They prevent evolution. They make it impossible for people to grow until the rot of corruption, dishonesty and repression seeps in and settles.

Society becomes stagnant and people stop building life around it.

Hostile environments

In neighbouring Zimbabwe, a combination of excessive rent-seeking, corruption and repression has made the country a hostile environment for many to live in.

As a result, many choose to migrate, close their businesses or avoid the country altogether. Those who remain are forced to practice a private form of government where civilians perform the functions of the state to survive.

In Uganda, opposition leaders such as Bobi Wine are constantly under threat of arbitrary arrest while human rights violations coded in law hold back many Ugandans from participating meaningfully in public life.

What makes the situation in Uganda more tragic is the enablement it receives from donors due to the country’s perceived importance to regional security.

Stifled potential

When studying the African diaspora, one realises that Africa has lost a lot of strong minds and potential.

Many Africans in the diaspora become key leaders in different fields. They do it well and are respected. This shows that the stagnant conditions in many countries in Africa are stifling the potential of many people and doing a disservice to the continent’s potential to contribute globally.

To achieve the river status – that of free-flowing ideas and embracing change and fair political transitions – here are a few recommendations for civil society, government leaders and opposition leaders.

First, civil society organisations (CSOs) should establish stronger relationships and networks with regional and continental CSOs. Currently, research shows that competition for donors, language barriers and misaligned priorities are weakening the potential for CSOs to effectively put pressure on regional bodies and domestic governments.

By establishing and implementing a long-term strategic agenda on regional issues, transnational networks of CSOs could provide the much-needed bulwark against repression and tyranny.

Second, opposition parties should practice a form of cooperative multipartyism that would focus on advocating for and working towards improved service delivery and institutional transparency and efficiency.

By leveraging combined strengths and agendas, opposition parties are more likely to make greater gains in policymaking bodies. Moreover, such cooperation could assist in strengthening the opposition in the face of authoritarian leaders.

Third, government leaders must begin creating long-term visions and standards for their countries. This requires the discipline to think of politics and public administration beyond the four-to-six-year election cycle.

Liberian human rights activist Tiawan Gongloe once said that government leaders should work as though each term were their last. If they assume that they are entitled to a second term, they forget the interests of the people in search of a second term.

Last, in a bid to reform the state in Africa such that it works for the public, all stakeholders in a country must perform with a united vision. This means giving credit to leaders when they consistently do the right thing while enforcing, challenging and remaining vigilant if there are looting, corruption and human rights violations.

The state does not belong to the government or its leaders.

The state belongs to all the people living in it. Like any relationship, it takes intentional commitment to establish a healthy, strong, functional and dynamic society.

This article originally appeared on the Daily Maverick

Photo: GovernmentZA Flickr